Sustainable Development Department

Middle East and North Africa Region

The World Bank

REDUCING CONFLICT RISK

CONFLICT, FRAGILITY AND DEVELOPMENT

THE MIDDLE EAST & NORTH AFRICA

in

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

REDUCING CONFLICT RISK

CONFLICT, FRAGILITY AND DEVELOPMENT

IN THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA

December, 2011

Sustainable Development Department

Middle East and North Africa Region

The World Bank

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-ii-

Disclaimer

This document is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and

Development/The World Bank. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this volume

do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments

they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The

boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply

any judgment on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the

endorsement of such boundaries.

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-iii-

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S

__________________________________________________________________________

DISCLAIMER

ii

ACRONYMS

v

FOREWORD

vi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

vii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

ix

I. INTRODUCTION

1

II. CONFLICTS IN MENA: DEVELOPMENT IMPACTS

III. CONFLICTS IN MENA: KEY DRIVERS

3

9

IV. THE WORLD BANK'S EXPERIENCE IN CONFLICT-AFFECTED COUNTRIES IN MENA

17

V. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR REDUCING THE RISK AND IMPACT OF CONFLICT

24

Bibliography

29

Annex: Background papers on conflict & development in MENA

30

Figures

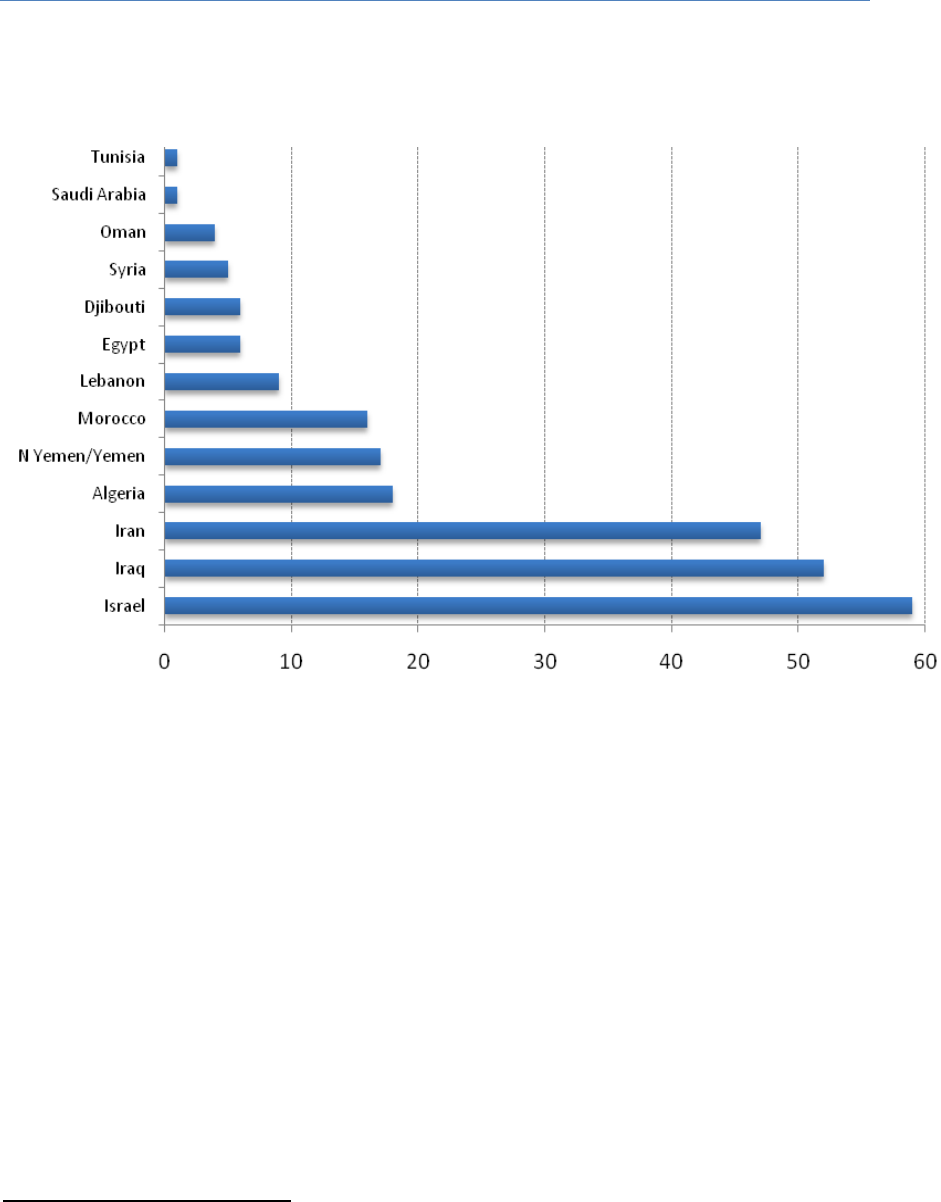

Figure 1: Conflict-Years in the MENA Region, 1960-2009

4

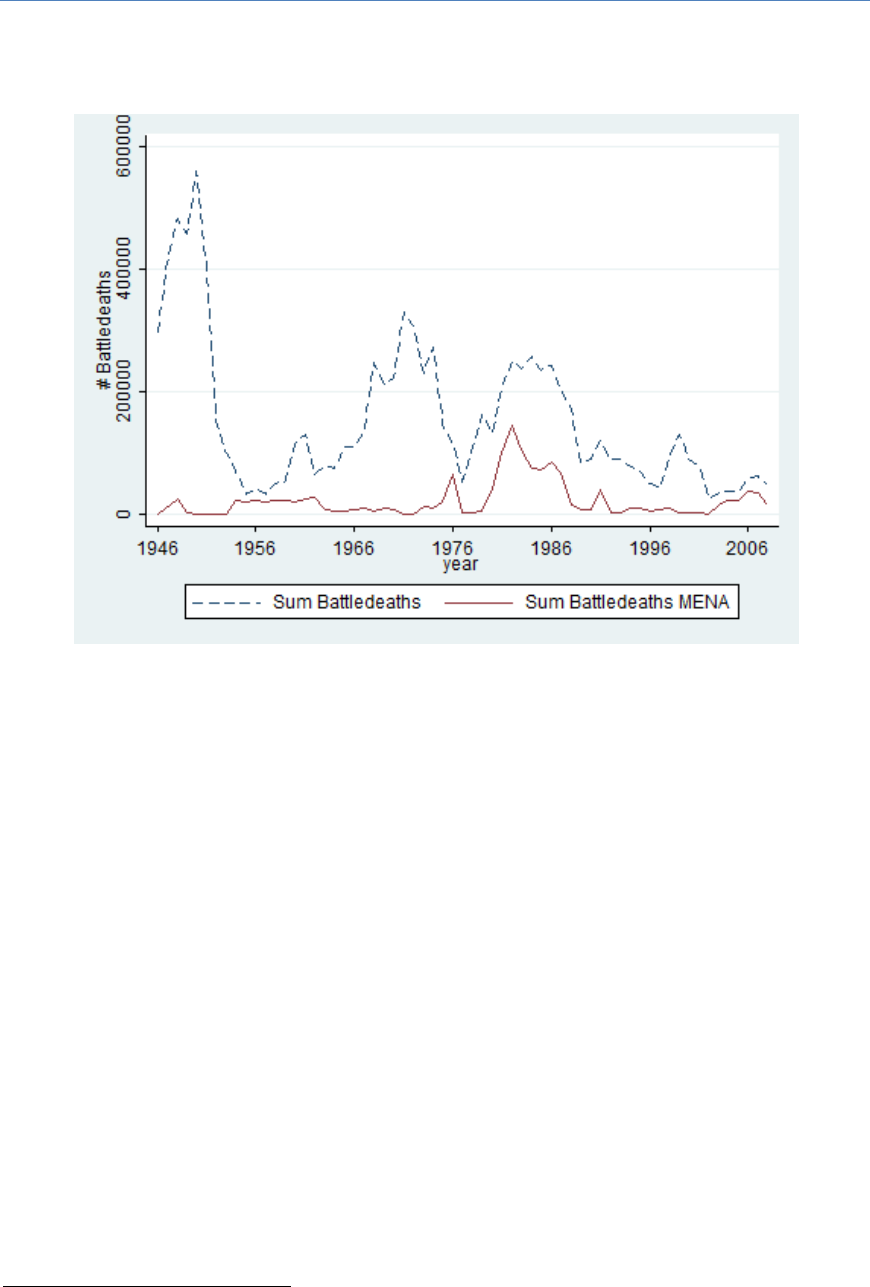

Figure 2: Total Battlefield Deaths in Global and MENA Conflicts, 1946-2008

6

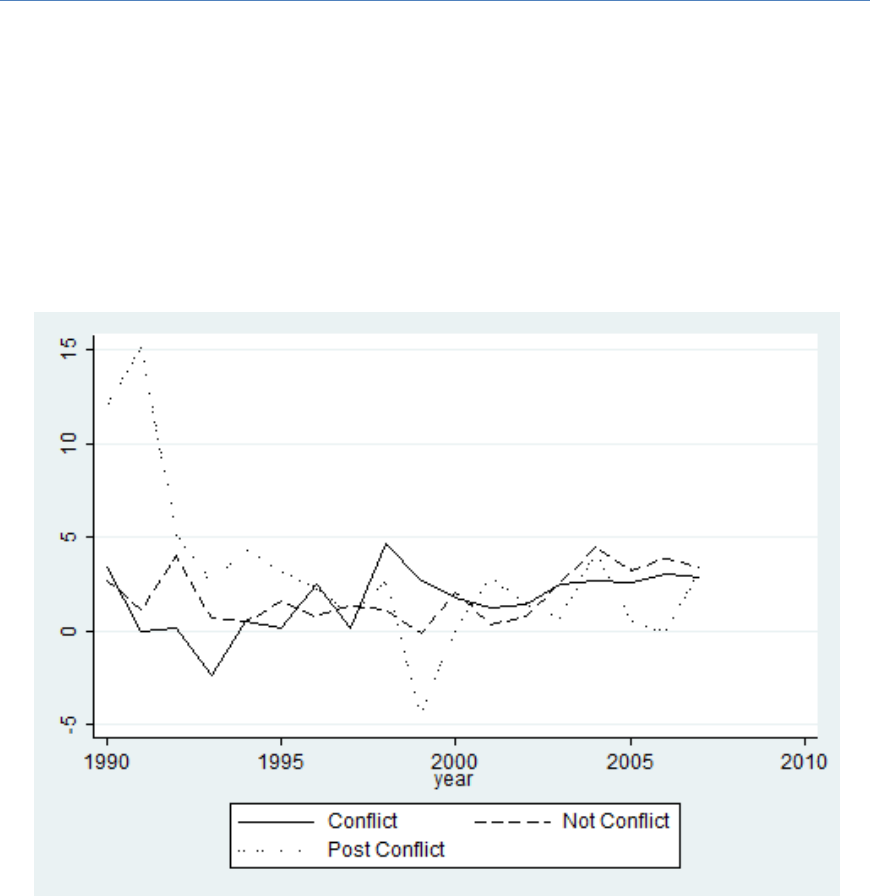

Figure 3: GDP Growth in MENA, 1990–2008

9

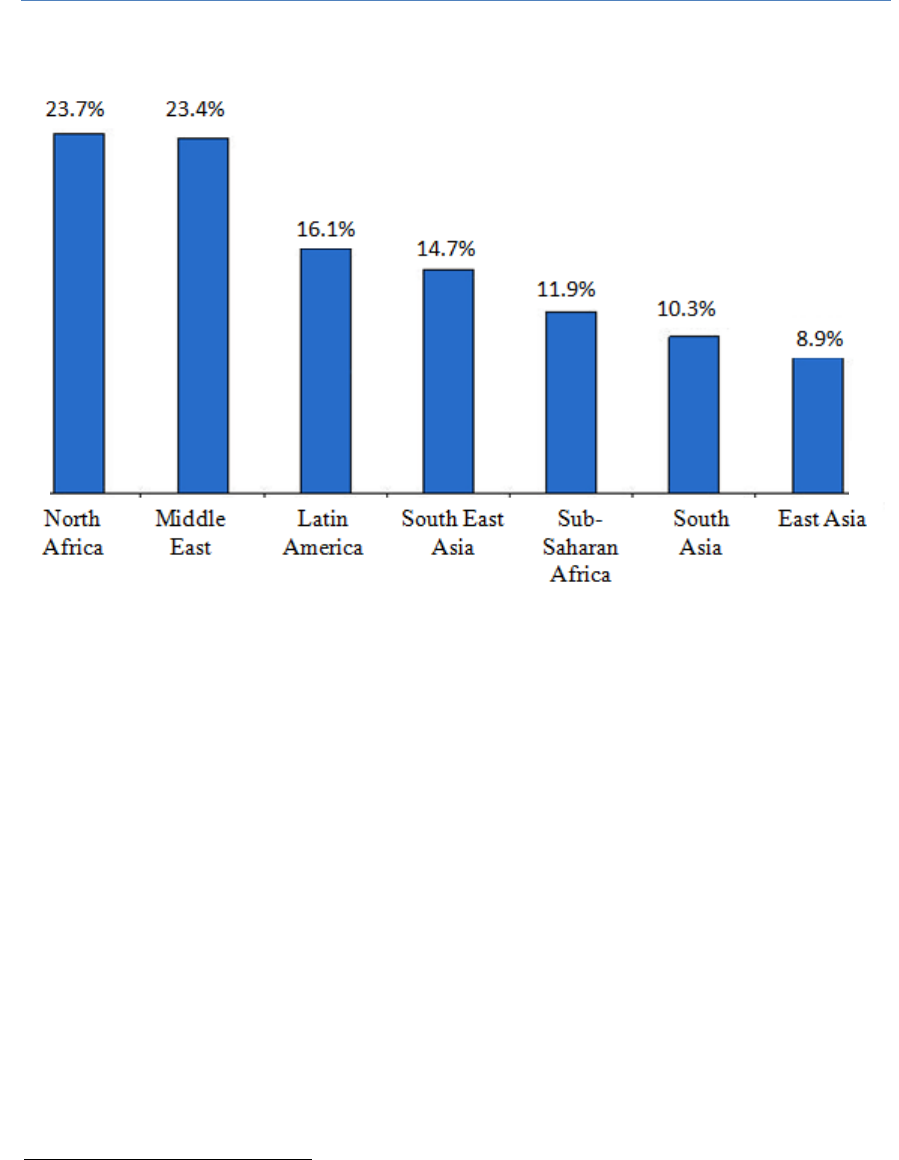

Figure 4: Youth (15-24 years of age) Unemployment in MENA & other regions, 2009

10

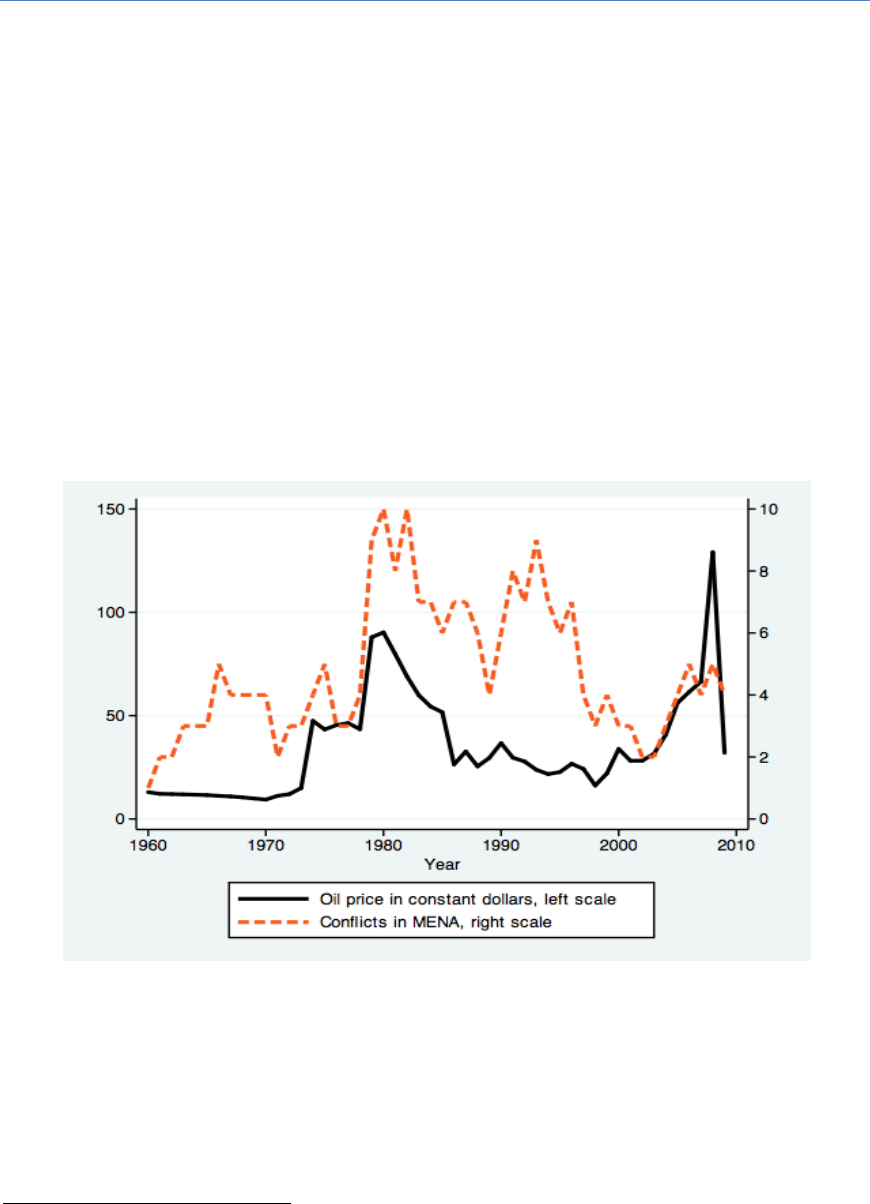

Figure 5: Oil Prices and Conflicts in MENA, 1960-2009

12

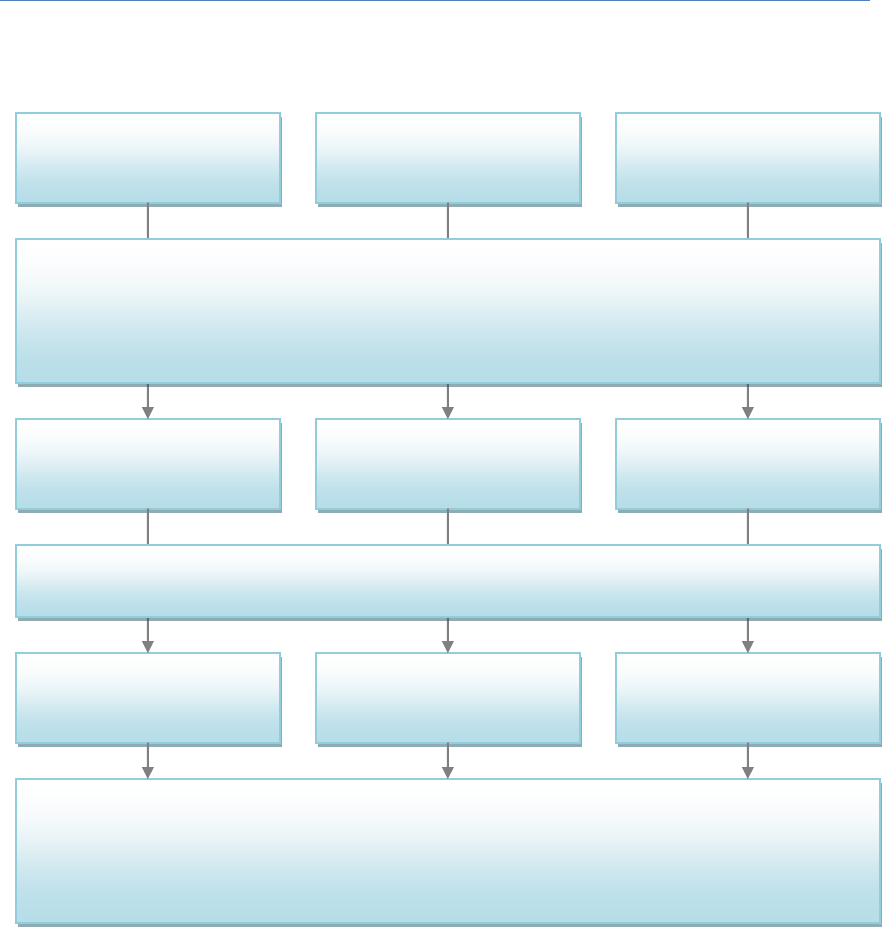

Figure 6: Representation of Interconnected Conflict Drivers in MENA

16

Figure 7: World Bank lending per source of funding

18

Figure 8: World Bank Lending in $ million per year

19

Figure 9: World Bank funding to MENA conflict-affected countries 1998-2010

20

Boxes

Box A: Key Terms: Conflict & Fragility

3

Box B: Gendered impacts of conflict in MENA

7

Box C: International and Intra-Regional Involvement

14

Box D: World Bank Engagement in Water Management in Conflict-Affected Countries

20

Table

Table 1: Average WGI Percentiles for MENA Countries, 2009

12

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-iv-

A C R O N Y M S

__________________________________________________________________________

DAC Development Assistance Committee (OECD)

EITI Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative

GDP Gross Domestic Product

IDP Internally Displaced Person

MDG Millennium Development Goal

MENA Middle East and North Africa (geographical region)

MNA Middle East and North Africa Region (World Bank division)

NGO Non-governmental Organization

ODA Official Development Assistance

OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

PRIO Peace Research Institute Oslo

PTS Political Terror Scale

UCDP Uppsala University Conflict Data Program

WDR World Development Report

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-v-

F O R E W O R D

__________________________________________________________________________

This regional study was originally conceived as a companion piece to the 2011 WDR (Conflict,

Security and Development), and it sets out to examine how the Bank's development assistance could not

only better address the impacts of conflict, but also could contribute to the reduction of conflict risk in

vulnerable countries. It re-examines the evidence on conflict incidence and causation in the region, then

looks more closely at the Bank's operational experience in four key countries, synthesizing these

regional findings with the global findings produced by the WDR to conclude with some broad

recommendations for the region.

This overview is based on original research and a series of background papers written throughout

2010, including an analysis of the Bank‟s portfolio in the Middle East and North Africa region. While

some findings were somewhat overtaken by events of the 'Arab Spring,' the report is intended to

capture the longer developmental trends and tools available to the Bank and its development partners.

Although development cooperation could be improved in the short term, the findings and

recommendations of this report are not designed to offer a „quick fix‟ in current circumstances. The

study has benefitted from consultation in the region and will be enhanced by continued dissemination

and discussion in the months ahead.

To be labeled „conflict-vulnerable‟ or „fragile‟ is not only unwelcome with client countries but also

contestable, and this label is often likely to be outdated before the ink on a static report is dry. The

findings and recommendations are therefore drafted in a broadly applicable sense so that countries

(and the Bank teams that serve them) may take away what they find most relevant and useful. The

study focuses on the Bank's performance in conflict-affected countries, and it does not profess to

advise partner agencies (many with broader mandates) on how to revise their operations. Our intention

is that the generic recommendations may stimulate more specific discussions about operational

priorities in specific country or regional situations. Ultimately, if client governments and beneficiaries

find the recommendations credible enough to re-examine their use of Bank assistance, we will have

achieved our objective.

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-vi-

A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S

__________________________________________________________________________

The study was prepared by a core team led by Colin Scott and Lene Lind (Social Development

Specialists, MNSSD) and consultants Caroline Bahnson, Malika Drissi, Jana El Horr and Steve Zyck

under the overall guidance of Laszlo Lovei (Director) and Sector Managers Franck Bousquet and

Anna Bjerde. The team would like to thank Nigel Roberts, Sarah Cliffe and Gary Milante (2011 WDR

team), Joseph Saba (consultant OPCFC), and Alexandre Marc (SDV), who all provided timely and

well-founded advice and inputs. Caroline Vagneron (MNACS) helped the team think through and

present its key messages at a critical point in the drafting, under the overall guidance of Emmanuel

Mbi and the MNACS team, who also provided essential support for the portfolio review. Key

background papers were provided by experts inside and outside of the World Bank, a full list of whom

can be found in Annex A. We are also grateful to the multitude of MNA staff who commented on

different sections of earlier drafts. The final and most important acknowledgement goes to the

Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Oslo, Norway, whose support made the study possible.

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-vii-

E X E C U T I V E S U M M A R Y

__________________________________________________________________________

1. This report is a companion piece to the World Development Report (WDR) 2011 on “Conflict,

Security, and Development”. The report is based on original research conducted throughout 2010 and

draws on the experience of the World Bank to better understand what drives conflict and fragility in

the MENA region and how development assistance may mitigate these potentially destructive forces.

Region-wide data and analysis is therefore almost exclusively drawn from the countries that

experienced violent conflict until late 2010, and herein particular Iraq, Lebanon, West Bank and Gaza,

and Yemen. While some findings may have been somewhat overtaken by events of the 'Arab Spring',

the report is intended to capture the longer, developmental trends and remedies available to the Bank

and its development partners. Although much can be done by development cooperation in the short

term, the findings and recommendations here are not designed to offer a „quick fix‟ in current

circumstances. Rather, additional and specific research is now warranted to analyze the various

dynamics currently at play in the region, and the potential support that can be offered by the

development community as transitions take shape.

2. Conflict in MENA has direct, long-lasting and detrimental effects on mortality.

Accounting for 15 percent of the world‟s conflicts while only housing 5.5 percent of the population,

the MENA region has seen a disproportionate level of conflict, particularly civil wars, since the end of

the Second World War. The nature of conflict in MENA (including continued exposure to aerial

bombardment and artillery shelling), has led to a large number of direct combat casualties,

disproportionate to the region‟s population. In addition, with a focus of public spending on security

and the atrophy of social services, reduced access to clean water, and displacement of civilian

populations during and after conflict means that up to three non-combatants die for each one

combatant killed during war in the region.

3. The economic impact of conflict is relatively limited in MENA, while other aspects of

living conditions deteriorate. While some countries in the region experience significant economic

hardship due to conflict, economic indicators in the region as a whole tends to recover more quickly

than in other parts of the world. Other indicators of human development are negatively impacted

however. MENA is home to both two of the top-three refugee-producing nations as well as four of the

top-five refugee-hosting locations, with high associated costs to both host nations and the affected

individuals. Conflict also decreases the proportion of the population with adequate access to water by

almost 0.9 percent for each year of conflict.

4. The quality of governance is not only a key casualty of war but also a major driver of

conflict and fragility. Countries which before the end of 2010 were either in or had recently emerged

from conflict in MENA tend to suffer from severe levels of political repression, including human

rights abuses, as well as weak institutions and governance. The longer and larger-scale the conflict, the

more authoritarian and abusive a state in MENA is likely to be. This regional study similarly finds that

the quality of governance is not only a key casualty of war, but also a major driver of conflict and

fragility. Econometric analysis suggests that, within MENA, poor governance increases conflict risk,

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-viii-

particularly the recurrence of conflict. This is a particularly salient finding for MENA given that the

countries in the region have consistently received some of the lowest governance scores in the world,

particularly those related to voice and accountability. Research thus suggests that MENA‟s conflict-

affected countries find themselves in vicious cycles whereby weak governance drives conflict, which

further erodes governance quality and drives up the likelihood of renewed warfare.

5. Dependence on natural resource rents erodes governance throughout the region.

Revenues, or „rents‟, derived from natural resources underlines the poor governance within MENA,

both in oil-producing nations and those countries dependent on financial flows from major oil

producers. Since 1960, the conflict rate in oil producing states has thus been 40 percent higher

compared to countries without oil. In short, MENA‟s sizable natural resource rents render the region

vulnerable to positive and negative price shocks, finance authoritarianism and prevent economic

diversification and the jobs which non-oil-based growth could bring. In addition, natural resource

revenues remove the state‟s obligation to earn the legitimacy necessary for extracting tax revenues, a

traditionally fundamental aspect in forging a social contract between the state and its citizenry.

Without such an obligation, states are impelled to rely more on food and fuel subsidies as well as

repression to either purchase or enforce citizen loyalty.

6. Large, unemployed youth cohorts may exacerbate conflict risk. Countries with large youth

cohorts or “bulges” face a significantly heightened risk of conflict. Such a finding is especially

relevant to the region given that young adults between the ages of 15 and 29 comprise up to 30 percent

of the MENA region‟s population and almost 47 percent of the working-age population. Such risks are

exacerbated by the limited economic prospects available to youth within MENA – a by-product of

limited non-oil growth, conflict and governance deficits – and the low economic returns on additional

education compared to other regions.

7. Political transitions are followed by several years of increased risk of conflict. Political

transitions, including those achieved peacefully and especially those involving change in state

leadership, may be followed by a significantly elevated risk of conflict onset. While international

concern regarding armed violence is generally the greatest during and in the immediate aftermath of

major political changes, the real risk may be delayed. Research shows that leadership changes in

MENA may not lead to immediate conflict, but have often been followed by conflict one or two years

later as newly arrived regimes and citizenries attempt to assert their authority and rights. Segments of

the population, driven by ethnic, religious, political or, at times, regional allegiances, seek to assert

their independence, while new leaders strive to demonstrate that they are firmly in control.

8. The World Bank has operated in fragile and conflict-affected states in MENA, but

perhaps not always consciously with conflict and fragility. This study provides a review of the

World Bank work in conflict-affected countries in MENA, namely Iraq, Lebanon, Yemen and the

West Bank and Gaza. The World Bank granted or lent almost US$5 billion to these four countries in

the period 1998-2010, of which almost half was provided to the water, education and urban

development sectors. Assessing the last decade of experience reveals that the Bank has proven capable

of implementing a wide range of different projects in these complex and at times insecure contexts,

using procedures that have facilitated both speedy and flexible responses. Experience in West Bank

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-ix-

and Gaza shows that the World Bank can play a leading technical role in a politically contentious

context when using adequate and tailored flexibility and decentralized human resources. Often,

however, the World Bank has found it hard to translate its understanding of local drivers of conflict

and fragility into its strategic and operational engagement. In effect, conflict is commonly treated as

something for the Bank to work “around” rather than as a core development challenge which must be

consciously addressed within the scope of the institution‟s mandate, and thus integrated as part of

operational design and implementation.

Recommendations

9. The findings of the WDR 2011 and the analysis included in this study lead to a set of strategic,

policy-oriented and programmatic recommendations which are applicable to the World Bank and

potentially to other development actors. As the region encompasses considerable diversity, it should

be noted that the following recommendations are general suggestions and may not necessarily be

relevant to all countries in MENA.

10. Adapt international approaches to ensure that international actors’ - including the

World Bank’s - priorities, strategies and incentives for MENA are aligned with the special

challenges faced by the region. Such a change in approach should in particular allow for a greater

tolerance for taking relevant risks and preparedness to employ less standard approaches, potentially

leading to higher rewards. This study also proposes to revisit the way the World Bank analyzes the

political economy of its clients, subsequently ensuring that the consequential more sophisticated

understanding of conflict drivers is incorporated into strategic and operational approaches. A

disaggregated examination of the spatial and social inequalities will for example allow for better

targeting and impact. Such detailed societal analysis should equally be applied to investment projects

and budget support operations. While the World Bank has mainly used its traditional development and

sectoral indicators to measure progress and success, it can only measure its impact on conflict by

introducing indicators related to conflict drivers and dynamics.

11. Address repeated cycles of violence in MENA by paying attention to the pivotal role of

governance and legitimate institutions. This study demonstrates how weak governance is both a

major driver of conflict as well as a function which is severely degraded by conflict. The prominence

of the governance agenda has been spreading across the region since early 2011; it should however be

stressed that governance is a particularly important variable in the recurrence of violent conflict. While

the specific governance priorities are ultimately set by the peoples of the region, it now appears that

human rights, inclusivity, justice, anti-corruption measures, and the establishment of a durable social

contract which contribute to state legitimacy, are all increasingly being demanded by people

throughout MENA. This study therefore strongly recommends development actors including the

World Bank to put increased focus on strengthening engagement with the supply and equally the

demand sides of governance. This could include on one hand emphasizing conflict-linked elements of

public sector management, such as equity, corruption, and natural resource management and

strengthening the rule of law and equal access to justice. These activities at the state level should be

complemented by efforts to increase citizen accountability through transparency, participation,

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-x-

enabling environment for civil society organizations as well as decentralized decision-making and

service delivery.

12. Promote Inclusive Growth through Employment Generation and Economic

Diversification. The costs associated with unemployment go well beyond economic hardship, as it

also impacts a social status and people‟s sense of dignity. Creating jobs, not least for the younger

strata of the populations in MENA, should therefore be at the forefront of development endeavors, not

as a byproduct of growth, but as a key objective in itself. Increased economic diversification away

from oil and gas could contribute to an increased demand for labor, while also decreasing rental

dependence with its common derivatives including vulnerability to price shocks and “rentierism”.

13. Marshalling regional and global action, experience and resources to address cross-

border challenges more effectively and capitalize on global experience. Considering that a number

of the developmental risks, challenges and conflict drivers are regional or even global in nature,

solutions might also be found outside bilateral or state-centric approaches. Additional attention could

be paid to regional governance and justice priorities through mechanisms such as the Extractive

Industries Transparency Initiative or in the area of rule of law. The provision of adequate and

predictable financing remains a challenge, so further use of multi-donor trust funds could help reduce

volatility and transaction costs for donors and recipients. The region is also home to a strong

development community not only at the state level, but there are also significant contributions from

non-governmental and private entities stemming from the “zakat” and almsgiving tradition. Finally, in

light of the rapid and complex transitions underway in the region, additional efforts should be made to

strengthen regional research capabilities and to provide training on governance and conflict issues.

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-1-

I. INTRODUCTION

1. As this study moved into its final stages, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) was

witnessing a level of protest and political transformation not seen for several decades.

1

An

uprising in Tunisia, which came to be known as the „Jasmine Revolution‟, led to the resignation

of President Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali, the country‟s ruler of nearly a quarter-century. Next fell a

seemingly more durable regime, that of Egypt‟s Hosni Mubarak, who was ultimately impelled to

hand control to the military after 30 years in power. Tahrir Square, the site of Cairo‟s largest

protests, became an important symbol throughout the region as demands for more representative,

legitimate and effective state systems erupted in Algeria, Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Libya,

Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Syria, and Yemen.

2

With few exceptions, salary increases for

public sector employees, promises of political liberalization and other gestures appeared to do

little to quiet demands for broad-based change. Violent responses to the protests in Bahrain,

Egypt, Syria, Libya, Yemen and elsewhere only exacerbated tensions and re-enlivened protests

and calls for change. Perceptions of the region and its internal dynamics began to change and

evolve. Autocratic and „authoritarian‟ states were no longer viewed as a source of stability, but as

core vulnerability for MENA.

3

2. The recent events, which will continue to unfold as the World Bank begins to disseminate

this study, have challenged much of the conventional wisdom regarding conflict and fragility in

the MENA region. They have also demonstrated the importance of going beyond the narrowly

construed media analyses of the region and reviewing the available quantitative and qualitative

body of evidence generated over time. This study aims to mobilize the experience of the World

Bank and the expertise of researchers and practitioners to better understand what drives conflict

and fragility in MENA and how development assistance can mitigate these potentially destructive

forces. This study was initiated more than a year before the recent political transitions in MENA,

and, therefore, does not specifically analyze or address the protests and leadership changes which

have emerged since December 2010. Any such analysis, in such a dynamic and novel context,

would be shallow and quickly outdated.

Background and Scope of the Study

3. This study was conceived as a companion piece to the World Development Report

(WDR) 2011, which tackles the theme of “Conflict, Security, and Development”.

4

It uses region-

specific data and experience in order to ground the WDR‟s findings firmly in the MENA context.

The production of this report began with the commissioning of a number of background papers

concerning conflict and development in the MENA region (see Annex A for a list of background

papers). This was supplemented by a review of the World Bank‟s experience in addressing the

1

For a useful overview, see S. Otterman and J. D. Goodman, “Hundreds of Thousands Protest Across the Mideast”,

New York Times, Feb. 25, 2011.

2

“Protests Force Change in Egypt, Tunisia, Jordan, Yemen”, Saudi News Today, Feb. 14, 2011.

3

See M. P. Posusney and M. P. Angrist, eds, “Authoritarianism in the Middle East: Regimes and Resistance”, Bouler,

C: Lynne Rienner, 2005.

4

See World Bank, “World Development Report 2011: Conflict, Security, and Development “, Washington, DC: World

Bank, 2011.

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-2-

challenges embedded in conflict-affected and fragile situations in the region. In addition, to

ensure the inclusion of voices and perspectives from within the MENA region itself, a series of

consultations and workshops were convened in Egypt, Lebanon, the West Bank, Yemen, and Iraq

as part of the WDR 2011 process.

5

4. Hence, as a complement to the WDR, this study has two overarching objectives. It aims

to go beyond the aggregate global analysis provided by the WDR and provide a regional analysis,

which reflects those aspects of conflict and fragility in MENA that may differ from a global

sample. Do conflicts in MENA share the characteristics and drivers of conflict with those in other

regions? And do they have the same impact on the lives of their citizens and the development of

their societies and economies? Based on this region-specific analysis, the second aim is to

examine to what extent development assistance, particularly that provided by the World Bank to

Iraq, Lebanon, the West Bank and Gaza, and Yemen, has addressed the specific nature of conflict

and fragility in MENA and how it may help to reduce the risk of conflict and mitigate fragility in

the future.

5. Conflict is a dynamic and highly complex phenomenon. A thorough examination

incorporating all its relevant aspects is beyond the scope and ambition of this particular report. A

number of choices and delimitations have thus been made in the production of this study. First

and foremost, the authors have chosen to focus on the drivers and impact of conflict and fragility

that are amenable to development policies and interventions. This is not to ignore or play down

the impact of historical, religious or global political factors, but is rather based on a recognition

that other actors are in better positions to analyze and address these issues. Secondly, the study

recognizes that conflict in general is an integral part of human coexistence and often a basic

element in societal change. Therefore, focus has been placed on violent conflict dating before the

end of 2010 (definition in box A below) and the human, social and economic destruction it

frequently entails. Criminal violence and insecurity also have not been included in the study.

Finally, as noted earlier, the study is not an attempt to analyze or be prescriptive of the „Arab

Spring‟. The analysis will primarily be based on data and evidence from situations that conform

to the definition of violent conflict before the end of 2010. However, links with the current

situation will be suggested, where relevant, and in case where the evidence points towards

potential risk reduction strategies. Certain of the study‟s findings could also be used as a starting

point for further in-depth research into the dynamics behind the potentially transformative events

taking place in the region in 2011.

5

Some records from these consultations are available online at: http://wdr2011.worldbank.org/consultations-map.

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-3-

II. CONFLICTS IN MENA: DEVELOPMENT IMPACTS

6. The number of conflicts in MENA has risen and fallen over the last decades broadly in

line with global trends. This number however, has been disproportionate to the region‟s

population as the MENA region experienced approximately 15 percent of worldwide conflicts

since 1945, yet accounts for only around 5.5 percent of the world‟s population and less than 10

percent of the world‟s nations.

6

This picture becomes even starker if only intra-state conflict is

considered, as the MENA region was the site of nearly one-third of all intra-state wars in the

world in the late 1970s until the mid-1990s. This trend has tapered off in the last decade in which

only around 10 percent of the world‟s conflicts and a similar proportion of civil wars took place

in the region. It should also be noted that while the total number of conflicts for MENA appears

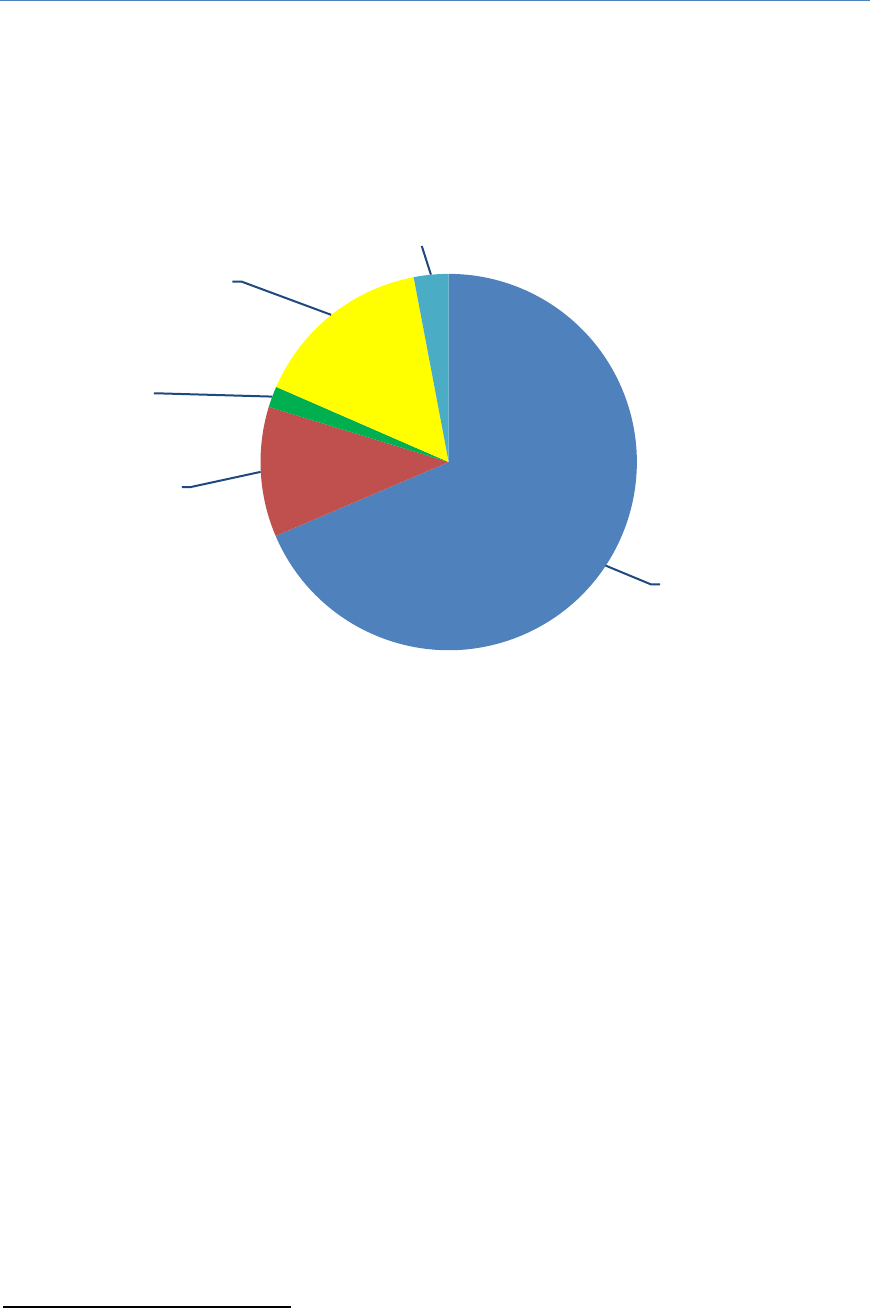

large, the distribution of conflict years between countries is highly uneven: 65 percent of conflict

in MENA since 1960 occurred in Israel, the West Bank and Gaza, Iran, and Iraq. Algeria, Yemen,

and Morocco accounted for another 21 percent of conflict years.

7

Most of the region‟s other

countries did not experience a single year of conflict in the past half century.

6

The population, for the purpose of these calculations, is estimated at 377,340,571 in 2010 relative to a global

population of 6,852,472,823. Conflict data are from the PRIO-Uppsala Armed Conflict Database.

7

For the purposes of this analysis, conflicts in North Yemen and the Republic of Yemen have been combined.

Box A: Key Terms: Conflict & Fragility

This study draws on the definition of conflict provided by the Peace Research Institute Oslo

(PRIO) and the Uppsala University Conflict Data Program (UCDP). According to this

definition, organized armed violence resulting in more than 25 battle-deaths per year

constitutes conflict while conflicts with more than 1,000 annual battle-deaths per year are

considered to be „major‟. However, this study also reflects the fact that definitions of conflict

intensity rooted in annual battle-deaths may be misleading given the harm which conflicts

cause beyond the battlefield and the high variations in battle-field deaths from year to year in

places such as the West Bank and Gaza.

With regards to fragility and fragile situations, this study adopts the definition used in the

WDR 2011, according to which fragile situations are “periods when states or institutions lack

the capacity, accountability, or legitimacy to mediate relations between citizen groups and

between citizens and the state, making them vulnerable to violence”. However, given the

controversy which has at times surrounded discussions of fragility this study maintains a

stronger focus upon conflict than fragility and views fragility primarily, building upon the

WDR 2011, as situations with an elevated level of vulnerability to violence.

Sources: World Bank data

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-4-

Figure 1: Conflict-Years in the MENA Region, 1960-2009

Source: Michael Ross, Nimah Mazaheri, and Kai Kaiser, “The „Resource Curse‟ in MENA” Resource Wealth,

Economic Shocks, and Conflict Risk”, background paper for the 2011 World Bank Study on Conflict and

Development in the MENA Region, 2011; calculated from data in Gleditsch et al. (2002) and Harbom and

Wallensteen (2010)

7. These numbers are based on data predating the „Arab Spring‟. Whether recent violence in

MENA will reverse the declining trend yet, again remains too early to assess. Moreover, the study

acknowledges that a regional view prevails that it is unlikely that MENA will achieve a durable

and equitable peace as long as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict continues

8

. The centrality of this

conflict plays a major role in influencing local and global perceptions of the region and has at

least partly motivated international interest, involvement, and development assistance to the

region.

9

Political scientists, economists, anthropologists, and other scholars have attempted to

characterize this conflict and examine its drivers.

10

Nearly every such analysis demonstrates that

this conflict has become itself a source of further tension and violence within the MENA region

and globally. While development actors and assistance have a critical role in West Bank and

Gaza, this study provides a differentiated view of the Bank‟s assistance across the region and a

need to analyze drivers and development responses in specific contexts.

8

Evidenced by our consultations in the region which characterized the conflict as Israeli-Arab, not just Israeli-

Palestinian.

9

Edward E. Azar, Paul Jureidini, Ronald McLaurin, “Protracted Social Conflict; Theory and Practice in the Middle

East”, Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Autumn, 1978), pp. 41-60

10

Dan Smith, “The State of the Middle East: an Atlas of Conflict and Resolution”, University of California Press,

Berkeley, 2

nd

edition, 2006, 2008

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-5-

Conflict's Impact on Human and Economic Development in MENA

8. The development community is increasingly realizing that conflict cannot be separated

from development agendas. Not a single low-income, fragile state has achieved any of the MDGs

and fragile, conflict-affected, and „recovering‟ states account for 77 percent of all school-age

children not enrolled in primary school, 61 percent of the world‟s poor, and 70 percent of infant

mortality.

11

Conflict shortens life expectancy and kills people on and off the battlefield – through

direct acts of violence and as a result of deprivation and reduced service provision – both during

conflict and for years after war has ended. Economic conditions also decline, and years of relative

peace and stability are required to allow a conflict-affected context to return to its pre-conflict

economic state. This same process of rapid decline during conflict followed by a slow and partial

return to the status quo ante commonly also applies to governance and the quality of public

administration.

12

Conflict also has intangible effects on cultures, societies and social cohesion,

important elements which has been beyond the scope of this study.

Millennium Development Goals

9. As mentioned earlier, the region has hosted a disproportional number of conflicts, which

have also tended to more lethal due to heavy international involvement and aerial bombardments.

Direct combat is not the only origin of causalities of war, even more people die as a result of

related causes, including the spread of infectious disease, the destruction of assets, the loss of

support mechanisms and the diversion of government spending away from basic services.

Estimates suggest that the number of indirect deaths attributable to conflict is roughly double the

actual number of direct conflict deaths in the MENA region.

13

Evidence from the conflict in Iraq

since 2003 demonstrates that three indirect deaths have occurred for each one direct combat

death. During the first Gulf War in 1991, this ratio was as high as 3.3 to one.

14

10. War-related deaths also result in shortened life expectancy. Globally, five years of

conflict decrease life expectancy by 4.5 years. In the MENA region such a decline would reduce

life expectancy from 72 to 67.5 years of age on average. However, data from the MENA region

suggests that the average conflict lasts four years and has a slightly more detrimental effect upon

life expectancy, resulting in a decline of approximately five years.

15

11

World Bank, “World Development Report 2011”, p. 63.

12

Hegre and Nygård, “The Governance-Conflict Trap in the ESCWA Region”, a paper for the UN-ESCWA study on

“The Governance Deficit and Conflict Relapse in the ESCWA Region”, 2011.

13

Gates, et al., “Consequences of Armed Conflict in the MENA Region”.

14

See Krause, Muggah, and Wennmann, “Global Burden of Armed Violence”, Geneva: Geneva Declaration

Secretariat, Small Arms Survey, 2008.

15

Gates, et al., “Consequences of Armed Conflict in the MENA Region”.

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-6-

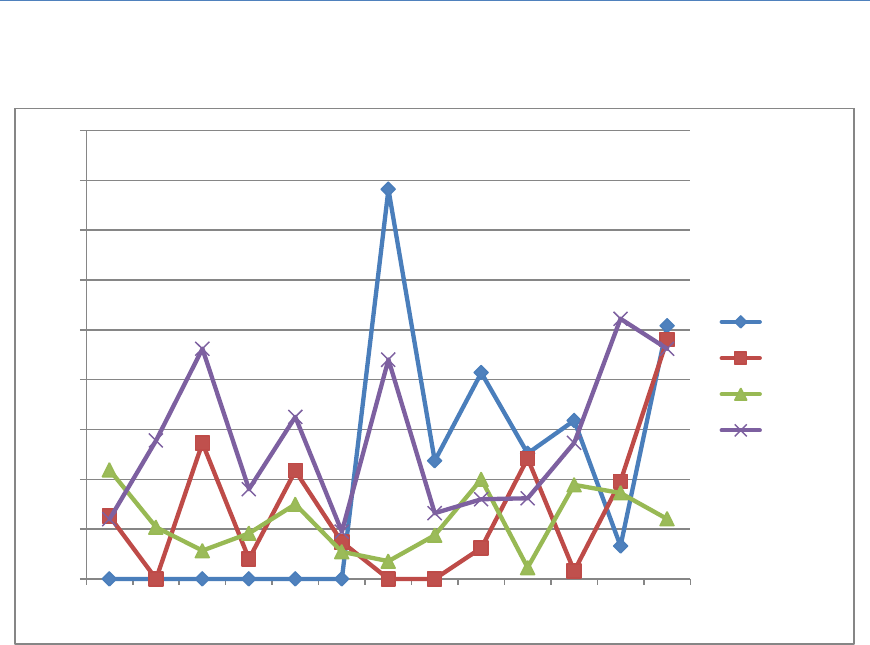

Figure 2: Total Battlefield Deaths in Global and MENA Conflicts, 1946-2008

Source: Gates, et al., “Consequences of Armed Conflict in the MENA Region”.

11. An increased rate of infant mortality has contributed significantly to shortened life

expectancy in the conflict-affected countries in the region. While the average increase of 1.17

percent in infant mortality rate per conflict year may appear small, the cumulative effect

translates into additional infant deaths comparable in number to direct battle deaths. In other

words, one infant which otherwise would have survived is likely to die for every person who dies

as a result of violence during the conflict. Further, the impact of conflict on infant mortality

persists for many years after violence has ended, in part due to its effect on health infrastructure

and services.

16

12. While conflict has clear detrimental effects on achieving the Millennium Development

Goals globally as described above (except combating HIV/AIDS), the correlation between

conflict and such deterioration is a lot less clear in the MENA context. In addition to life

expectancy and infant mortality discussed above, conflict in MENA negatively affects primary

school enrolment gender ratios, and access to water. Econometric analysis shows that one year of

minor conflict decrease the population with adequate access to water with almost 0.9 percent. On

average, 10 percent of the populations in MENA do not have sufficient access to water, after five

years of conflict this number would rise to almost 15 percent.

17

16

Gates, et al., “Consequences of Armed Conflict in the MENA Region”.

17

Gates, et al., “Consequences of Armed Conflict in the MENA Region”.

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-7-

Displacement

13. Negative impacts of conflict on health and mortality may particularly affect refugee

populations and internally displaced persons (IDPs). The MENA region is home to two of the top

three refugee-producing nations, Palestine and Iraq, as well as four of the top five refugee-hosting

locations, including the West Bank (762,000 refugees), the Gaza Strip (1.1 million), Syria (1.76

million), Iran (1.0 million), and Jordan (621,000).

18

Furthermore, the West Bank and Gaza,

Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon have the highest proportion of refugees to host-nation populations in

the world. In many locations in the MENA region, displacement has not been a temporary

phenomenon but rather one which has persisted for decades uninterrupted.

19

14. Refugees put significant economic and social pressure on their host governments and

societies. According to the Syrian government, for example, demand for subsidized bread rose by

35 percent after the Iraqi refugee influx in 2006, costing the Syrian state US$34 million, while

18

Scott and Nezam, “More Than a Humanitarian Matter? Displacement and Development in the Middle East”,

background paper for the World Bank Study on Conflict and Fragility in the MNA Region, 2009.

19

World Bank, “World Development Report 2011”, p. 61.

Box B: Gendered impacts of conflict in MENA

As elsewhere, the impacts of conflict affect men and women differently in the MENA region. However,

these gender-specific impacts are more nuanced within conflict-affected and fragile countries in the

region, depending on the particular contexts. For example in 2000 globally, in non-conflict countries,

around 98 percent of girls received primary education whereas in countries in active conflict this figure

was down to 91 percent, with post-conflict countries in between. However, cross-regional research for

this study suggests there may be no statistically significant impact of conflict on girls‟ access to

education. This finding may be influenced by data paucity or by opposing forces which cancel each

other out. For instance, girls‟ access to formal education systems may be interrupted during conflict, but

local and international actors‟ aid programs compensate for this loss.

Another example is a World Bank report from 2010 relaying findings on the gendered dimensions of

conflict and economic collapse in the West Bank and Gaza. The report notes that while economic

hardship has allowed educated women, in particular, to explore various employment opportunities and

take a greater role outside of the home, it has forced many women into low-paying, menial work or has

pushed them to take the risk of borrowing money on behalf of their families. Even where such

opportunities may be considered “empowering” by some within and outside of the Palestinian context,

the report notes that many women are not comfortable with the new roles, with the added risk (e.g., with

the need to face Israeli checkpoints), or with the marital disharmony that their new economic role often

inspired. Some men, the report notes, have grown increasingly depressed, angry, and hostile as they feel

humiliated by harsh treatment and unemployment.

Sources: Gates, et al., “Consequences of Armed Conflict in the MENA Region” and World Bank “Checkpoints and Barriers:

Searching for Livelihoods in the West Bank and Gaza – Gender Dimensions of Economic Collapse” , Washington, DC: World

Bank, 2010.

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-8-

demand for water rose by 21 percent, at a cost of almost US$7 million per year.

20

Other costs of

hosting refugee populations include social services and security. Refugee populations may also

contribute to political instability in the region; notable examples of conflicts which involved and

were partly influenced by refugee inflows include Black September in Jordan in 1970, the

Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990), and the more recent violence in and around the Nahr el-Bared

Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon in 2007.

21

15. Per capita income for Palestinian refugees were also stifled; while the average

Jordanian‟s per capita monthly income was US$183, it was US$91 for a Palestinian refugee. In

Lebanon, a Palestinian refugee could expect to earn only one-quarter as much as the average

Lebanese (US$127 vs. US$501 per month).

22

In addition to limited employment opportunities

and reduced income, refugees are subject to overcrowding and poor-quality housing in many

instances.

23

While discussions of conflict-induced displacement in MENA had commonly focused

on the situation of Palestinians, the recent war in Iraq has created another major refugee and IDP

crisis with an estimated 1.7 million refugees in Syria, Jordan and Lebanon.

24

Rather than settling

in camps, most Iraqi refugees have integrated themselves into urban areas, making them difficult

to identify and assist. Their informal status forces them to work long hours for relatively little

money; poverty and host governments‟ reluctance to open schools to Iraqi refugees have forced

some Iraqi children into the labor market.

25

Economic Development

16. The WDR 2011 finds that “countries affected by violence throughout the 1980s lagged in

poverty reduction by 8 percentage points, and those which experienced major violence

throughout the 1980s and 1990s lagged by 16 percentage points”.

26

As this finding suggests, the

economic impact of conflict is frequently long-lasting. However, in MENA this effect is

somewhat muted thanks to its oil wealth and the remarkable resiliency of many of the region‟s

non-oil economies. In MENA, the speed of recovery from conflict in economic terms can at times

(with exceptions) be quite impressive.

27

Lebanon, for instance, managed to grow its economy

during its civil war, and, following the 2006 „July War”, the country experienced GDP growth of

more than nine percent per annum. Relative to other regions of the world, where the negative and

lasting economic consequences of war are readily certain, some countries in post-conflict

situations in MENA have a greater ability to recover.

28

MENA countries, whether because of the

20

Al-Khalidi, Ashraf, Hoffman, and Tanner, “Iraqi Refugees in the Syrian Arab Republic: A Field-Based Snapshot,”

Brookings-Bern Project on Internal Displacement, June 2007.

21

Scott and Nezam, “More Than a Humanitarian Matter? Displacement and Development in the Middle East”.

22

Bocco, Brunner, Al Husseini, Lapeyre, and Zureik, “The Living Conditions of the Palestine Refugees registered with

UNRWA in Jordan, Lebanon, the Syrian Arab Republic, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank”, Geneva and Louvain:

Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva and the Catholic University of Louvain, 2007.

23

For instance, 70 percent of Palestinians in refugee camps in Jordan report overcrowding; that number is 73 percent in

Syria and 71 percent in Lebanon. See Bocco, et al., “The Living Conditions of the Palestine Refugees”, p. 92.

24

See Scott and Nezam, “More Than a Humanitarian Matter? Displacement and Development in the Middle East”.

25

Ibid.

26

World Bank, “World Development Report 2011”, p. 60.

27

Ibid.

28

Gates, et al., “Consequences of Armed Conflict in the MENA Region”.

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-9-

region‟s oil revenues, an entrepreneurial spirit, or other factors, have the ability to experience

rapid post-conflict growth. For some this level may allow them to return to an economic position

similar to that of countries which had not experienced a conflict. Of course, the ability of some

MENA states to grow quickly after conflict should not be taken to mean that many others,

including Yemen and the West Bank and Gaza, do not continue to experience significant

economic hardship before, during, and after conflict.

Figure 3: GDP Growth in MENA, 1990–2008

Source: Gates, et al., “Consequences of Armed Conflict in the MENA Region”.

III. CONFLICTS IN MENA: KEY DRIVERS

17. This section examines those „drivers‟ which make countries within the MENA region

more (or less) likely to experience conflict. The choice of the term „drivers‟ over the narrower

„causes‟ is deliberate, as the term implies a more contextually situated and dynamic nature. The

specific drivers assessed within this study include the following: (i) low or declining per capita

incomes, (ii) large youth cohorts, (iii) regime types and transitions, (iv) deficits in the quality of

governance, (v) energy (oil and gas) resource dependence, (vi) and identity and inequality. This

list of issues is far from exhaustive, focusing on those drivers which appear to have general

applicability across the MENA region rather than those specific to particular countries or

contexts. For example, religious fractionalization may be an important driver of conflict in certain

situations, but econometric research done for the study showed no overall regional causality

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-10-

between the two.

29

Further, emphasis is placed on factors amenable to mitigation through

development intervention. This may result in larger political and diplomatic issues such as

disputed borders or regional and international interference, which are relevant to the MENA

region but not part of the World Bank mandate, receiving less attention.

Economic Decline and Large Youth Cohorts

18. Low per capita incomes increase the risk of conflict onset in the MENA region, but their

effect appears significantly weaker in MENA than for a global sample of countries. For instance,

a relative decline in per capita income of 10 percent (relative to the preceding level of income) is

likely to render a country at greater risk of conflict elsewhere in the world than in MENA. The

interplay of economics and conflict in MENA is at best limited and other variables either mediate

the effects of economic factors or play much larger roles as drivers of conflict in the region.

30

19. Such a finding highlights the inadequacy of standalone economic variables as sources of

conflict risk. Research suggests that poor economic performance may be far more likely to lead to

conflict when significant numbers of youth, particularly unemployed young men, are present.

Large youth cohorts do not in themselves lead to instability or conflict; rather the conflict

potential of youth bulges is linked to the opportunity structure determined by factors such as

educational attainment, employment opportunities, family formation, and means of political and

civic participation.

31

However, a correlation between populations with a large youth cohort

relative to the adult age population, and an increase in the likelihood of domestic armed conflict

has been shown.

32

An increase in youth bulges of one percentage point increases the risk of

conflict by approximately seven percent, while countries with youth bulges of 35 percent are

three times more likely to experience conflict than countries with a youth bulge equal to the

median for developed countries.

33

29

Sambanis and Choucair-Vizoso, “Conflict and Development in the Middle East and North Africa”.

30

Sambanis and Choucair-Vizoso, “Conflict and Development in the Middle East and North Africa”.

31

Barakat, Paulson, and Urdal, “Youth, Transition, and Conflict in the Middle East and North Africa”, background

paper for the 2011 World Bank Study on Conflict and Development in the MNA Region, 2010.

32

Stateveig, “Young and the Restless: Population Age Structure and Civil War”, ECSP Report 11, 2009, pp. 12-19;

Urdal, “The Devil in the Demographics: The Effect of Youth Bulges on Domestic Armed Conflict, 1950-2000”, World

Bank Social Development Paper, Washington, DC: World Bank, Conflict Prevention and Reconstruction Unit, 2004.

33

Urdal, “The Devil in the Demographics”, p. 9.

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-11-

Figure 4: Youth (15-24 years of age) Unemployment in MENA and Other Regions, 2009

Source: ILO, Global Employment Trends for Youth , Geneva, International Labour Office, Aug. 2010, p. 63.

Regime Types and Transitions

20. Globally, evidence suggests that regimes which are neither authoritarian nor genuinely

democratic have the greatest vulnerability to conflict onset.

34

Yet, data on MENA up to 2010

suggests that “anocratic” (or semi-democratic) regimes have in fact been more resilient in MENA

countries than anywhere else in the world. A MENA semi-democracy was “many times more

stable than similar regimes in other parts of the world - much more stable than a Sub-Saharan

African democracy, and more stable than autocracies in most parts of the world”.

35

In contrast to

global trends since the 1960s, MENA countries had not democratized and the region has been

characterized by “a freedom deficit,” as coined by the first UNDP Arab Human Development

Report.

36

21. MENA accounted for 17 percent of the world‟s coups between 1946 and 2006, and was

home to two of the world‟s eight most coup-prone countries (Syria with 20 coups and Iraq with

15).

37

Thirty-five percent of all leaders in MENA entered power in an irregular way, such as

through coups. Surprisingly, however, statistical analysis showed that having a coup in the last

three years does not increase civil war risk.

38

Instead, data from MENA suggests that changes in

34

Barakat and Urdal, “Breaking the Waves? Does Education Mediate the Relationship Between Youth Bulges and

Political Violence?”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5114, 2009; Hegre, Ellingsen, Gates and Gleditsch,

"Toward a Democratic Civil Peace? Democracy, Political Change, and Civil War, 1816–1992", American Political

Science Review, 95:1, 2001, pp. 33-48.

35

Gates, et al., “Consequences of Armed Conflict in the MENA Region”.

36

“Arab Human Development Report”, 2002.

37

Syria is the one country in the world with three successful coups in 1949 and three attempts in 1975.

38

Sambanis and Choucair-Vizoso, “Conflict and Development in the Middle East and North Africa”.

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-12-

leadership within a country, particularly those which bring a country from one autocratic regime

to another, have historically resulted in greater susceptibility to conflict onset.

39

Somewhat

unexpectedly, conflicts did not occur alongside or immediately following the regime changes or

coups in these cases; rather, political violence emerged within two years of those leadership

changes.

40

In some cases, the new leadership was perceived as being weak spurring groups to

challenge the regime and pursue their own interests. In other instances, the conflict was more

closely linked to the introduction of internal security strategies intended to help newly

empowered leaders to firmly establish their control - more violent military action prompted more

violent insurgencies which evolved into further violence.

Weak Governance and Rental Dependence

22. Econometric analysis carried out for this MENA-specific study indicates the existence of

a strong linkage between conflict and poor governance in the Middle East and North Africa. One

of the study‟s background papers investigated a set of indicators capturing several aspects of

governance: formal political institutions, political exclusion and repression, the rule of law,

corruption, bureaucratic quality, military influence in politics and economic policies. By

constructing a composite index, the authors find that not only is it “the worst governed region in

the world”, there was no improvement during the reviewed period.

41

In fact, most indicators were

stagnant or deteriorating. Using statistical models to estimate the risk of conflict relapse in the

region, the authors show how the risk of renewed conflict in countries with good governance

drops rapidly after the end of the conflict. In those characterized by weak governance however,

this process takes a lot longer. To make matters worse, conflict then leads to a further reduction in

the quality of governance and undermines the near-term prospects for improved governance in

MENA.

42

Put another way, a poorly governed country is likely to fall into a self-reinforcing cycle

of conflict and bad governance.

Table 1: Average WGI Percentiles for MENA Countries, 2009

Governance Indicator

Regional

Average

Iraq

Lebanon

W. Bank &

Gaza

Yemen

Voice and Accountability

23.2

13.7

35.5

20.4

11.8

Political Stability

38.6

1.9

9.0

3.8

2.4

Government Effectiveness

47.8

8.1

30.5

21.4

11.4

Regulatory Quality

48.3

15.2

50.5

49.5

29.5

Rule of Law

49.0

1.4

32.1

44.8

13.2

Control of Corruption

49.1

4.8

22.9

39.0

15.2

Note: Given that percentiles are displayed above, the global average for each governance indicator is approximately 50. Scores

closest to 100 represent the “best” governance scores and those closer to 0 are the “worst”.

Source: http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.asp

39

Sambanis and Choucair-Vizoso, “Conflict and Development in the Middle East and North Africa”.

40

Ibid. These leadership changes comprise: Algeria (1962), Iran (1979), Iraq (1959 and 1961-70), Oman (1971-75),

Turkey (1984-99), and North Yemen (1948 and 1962-70).

41

Hegre and Nygård, “The Governance-Conflict Trap in the ESCWA Region”.

42

Hegre and Nygård, “The Governance-Conflict Trap in the ESCWA Region”.

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-13-

23. Even when compared with countries that have similar incomes, the MENA region ranks

at the bottom on the Worldwide Governance Indicators index of overall governance quality. One

possible contributor to this weak governance is the presence of oil revenues not only in oil-

exporting nations but also in states which are significantly dependent upon oil and cash flows

from oil exporters.

43

Among countries at all income levels since 1960, the conflict rate in the oil

states has been about 40 percent greater than in non-oil states. And since the Cold War ended, it

has been almost 50 percent greater. Conflict risk among low-income oil states, such as Yemen,

has been twice as great as in non-oil states since 1992.

44

Countries with large oil revenues and

small populations are the least likely to experience conflict while countries such as Iraq, Iran, and

Algeria with large oil revenues and sizable populations will have an average (though not

necessarily elevated) level of conflict risk.

45

Figure 5: Oil Prices and Conflicts in MENA, 1960-2009

Source: Ross, et al. “The “Resource Curse” in MENA? Resource Wealth, Economic Shocks, and Conflict Risk”.

24. Furthermore, the instability of global oil prices also leads to macroeconomic shocks in

major oil-exporting nations which may add to the risk of conflict. For example, MENA‟s conflict

trend closely mirrored the global trend in number of conflicts except for period from 1978 to

1984, which included positive (1978-79) as well as negative (1979-84) oil price shocks.

46

Finally,

as suggested in the preceding section on governance quality, research has demonstrated the

corrosive influence which natural resource wealth, particularly oil wealth, may have upon the

43

Ross, Mazaheri, and Kaiser, “The „Resource Curse‟ in MENA”.

44

Here the calculations are based on a definition of “low-income countries” which only includes those below the

$5,000 per capita threshold; MENA states such as Libya, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia are, hence, not included in the

calculations.

45

Lust-Okar and Sambanis, “The Political Economy of Internal Armed Conflict in the Middle East and North Africa”.

46

Ross, Mazaheri, and Kaiser, “The „Resource Curse‟ in MENA”.

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-14-

quality of governance and public institutions.

47

Oil and gas revenues or „rents‟ may thus be

understood as an intervening variable which increases conflict risk by weakening the quality of

governance. One explanatory theory is that states with significant oil and gas revenues do not

need to tax their citizenries and, hence, have little need to earn the acquiescence of their

populations to taxation. Instead, the state is able to use its resource-derived wealth to provide

subsidies and distribute rents through other means.

48

Alternatively, rentier states, as rentally

dependent nations are often referred to, may bypass the bulk of the populace and, instead, focus

their efforts on buying the loyalty and allegiance of a narrow band of key elites.

49

The

securitization of oil-exporting nations has further been facilitated and encouraged (e.g., through

the provision of military hardware, training, etc.) by oil-importing nations.

50

Identity and Inequality

25. Identity and inequality are among the additional range of drivers of conflict and fragility

discussed in the literature and other background studies. Yet data limitations make it difficult to

assess to what degree these are applicable in MENA with the same degree of precision and

objectivity as some of the previously discussed factors. For instance, some measures of identity

consider MENA to be among the most homogenous regions of the world, with a primarily Arab

background and limited degree of linguistic and religious diversity. Yet other measures which

account for sectarianism and other factors provide a divergent perspective.

51

Some studies find

that dominance by one identity group in the MENA region renders conflict more likely but finds

that fractionalization – the division of societies between several identity groupings without a

47

Barma, Kaiser, and Tuan Minh Le, “Rents to Riches? The Political Economy of Natural Resource Led

Development”, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2011.

48

Al-Rasheed, “A History of Saudi Arabia”, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002; Vandewalle, “Libya since

Independence: Oil and State-Building”, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998.

49

For a case study of this dynamic in Iran, see Karshenas, “Oil, State, and Industrialization in Iran”, New York:

Cambridge University Press, 1990.

50

Ross, Mazaheri, and Kaiser, “The „Resource Curse‟ in MENA”.

51

See discussion of various classification and coding problems related to fractionalization in Sambanis and Choucair-

Vizoso, “Conflict and Development in the Middle East and North Africa”.

Box C: International and Intra-Regional Involvement

Although beyond the scope of development intervention, the study acknowledges that the involvement

of outside nations, whether regional or foreign actors, has been another factor influencing conflict in

MENA. Such involvement may entail military invasion and intervention, as in Iraq‟s invasion of

Kuwait in 1990 or the international invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Alternatively, they may involve the provision of financing, materials, weapons, training, technical

assistance, logistical support, intelligence, or diplomatic backing to governments, political factions,

non-state actors, or others in a foreign country. External support to Israel, and Israeli, Syrian, Iranian,

and other support to various factions within Lebanon are just some examples from MENA.

Sources: World Bank data

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-15-

single one being dominant – does not reduce conflict risk, thus providing a useful yet

theoretically unsatisfying explanation of the identity conflict interface in the region.

52

26. Evidence does suggest, however, that identity combined with horizontal equality (e.g., on

the basis of religion, ethnicity, etc.) may have a relation to conflict. In the MENA region

specifically, horizontal economic inequality between Lebanon‟s various regions and populations

appeared to play a major role in the country‟s civil war despite the fact that overall economic

growth continued.

53

Differential growth rates, particularly the implementation of state policies

exacerbating disparities in access to resources, have also been linked to several conflicts in the

region.

54

27. MENA has one the most equal income distributions in the world as measured by the Gini

coefficient, and is closely on a par with Europe, Central Asia and South Asia. It is significantly

lower than Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa. MENA has also had the largest reduction in

income inequality between the 1980s and 1990s.

55

This measurement only quantifies vertical

inequality (i.e., the level of inequality between individuals without reference to inter-group

differences) which is believed to foster criminal activity and violence. Horizontal inequality

(inter-group or inter-regional inequality) has on the other hand been associated with conflict

onset.

56

Horizontal inequality also has an important non-material side. When inequalities result

from inter-group differences in justice, inclusion and access to power, material imbalances in

wealth and income are only one outcome. In addition, “economic stresses” may be amplified by

social factors such as “humiliation, pride, [shame], and desire for affiliation”

57

As in the case of

ethnic fractionalization, problems of coding and collection of data still hinder thorough analysis

of the relationship between horizontal inequality and conflict.

Merging Drivers and Impacts of Conflict in MENA

28. The concept of a „conflict trap‟ emerged from the observation that conflicts produce (or

re-create) conditions which may cause future conflict in a cyclical manner. Ninety percent of

conflicts which began in the first decade of the 21st Century were in countries which had already

experienced a civil war. By comparison, the same held true for only 43 percent of conflicts in the

1960s and 57 percent of conflicts in the 1970s.

58

52

See Sørli, Gleditsch and Strand, “Why Is There So Much Conflict in the Middle East?”, Journal of Conflict

Resolution, 49:1, 2005, p. 151.

53

Kamal, “Lebanon explodes,” MERIP Reports, 44, 1976; and Makdisi and Sadaka, “The Lebanese Civil War, 1975–

1990” in Collier and Sambanis, eds, “Understanding Civil War: Evidence and Analysis”, vol. 2, Washington, DC,

World Bank, 2005.

54

Jones, “Among ministers, mavericks and mandarins‟: Britain, covert action and Yemen Civil War, 1962-64,” Middle

Eastern Studies, 40, 2004, pp. 99-126.

55

Sambanis and Choucair-Vizoso, “Conflict and Development in the Middle East and North Africa”.

56

This issue is examined in greater detail in Chapter 2 of the “World Development Report 2011”.

57

World Bank, “World Development Report 2011”, pp. 81-82.

58

Ibid.

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-16-

29. Such a finding blurs the difference between drivers and impacts of conflict and fragility.

The role of economic conditions in driving repeated cycles of conflict, creating an „economic

conflict trap‟, was identified in 2003. This revealed that a “country that first falls into the trap is

10 times more at risk of a new war just after the war has ended, than before it started. If the

country succeeds in maintaining post-conflict peace for 10 years or so, the risk is considerably

reduced, but remains at a higher level than before the conflict”.

59

However, as previously noted in

this chapter, data shows that the most powerful drivers of conflict and fragility within MENA are

political (e.g., regime transitions, weak governance, rental dependence, and horizontal inequality)

rather than macroeconomic.

30. The „political conflict trap‟ operates similarly to an economic conflict trap. Conflict

within the MENA region induces leaders to become increasingly authoritarian. Conflict leads to

increased oppression and narrows or nearly eliminates opportunities for political expression or

opposition. Such a state of affairs exists not only during the conflict but also in the post-conflict

years as leaders come to fear that any loosening of their political and military grip could invite

further opposition. This situation limits economic growth and leads to widespread frustration

among a significant portion of the citizenry. Devoid of formal channels through which to

peacefully express its dissatisfaction, this citizenry may turn to protests, riots, terrorism,

insurgency, or conflict. Once again, the state responds to these challenges by further clamping

down and re-charging the political conflict cycle. Demonstrating the mechanisms underlying the

political conflict trap, 80 percent of MENA countries which were in the midst of a relatively

long-term conflict, or “durable war”, received the worst possible score on the Political Terror

Scale (PTS), meaning they routinely commit large-scale human rights abuses against their own

citizenries.

60

31. As the example of the role of rents in governance discussed above shows, political and

economic factors driving conflicts cannot be seen as neatly separate factors. Similarly, the various

drivers identified above may also „play‟ various roles, as some may contribute the initial

instigation of the conflict, whereas others may help explain escalation or recurrence. Ultimately, a

number of political, economic and social drivers operate together leading to violence and

instability. The resulting responses, whether increased authoritarianism and repression or

decreased economic opportunity, entrench original drivers or can create new grievances. The

diagram below attempts to give a stylized representation of how economic and governance

drivers can work in tandem to entrench a conflict trap.

59

Collier, et al., “Breaking the conflict trap”, p. 104.

60

See the Political Terror Scale web site: http://www.politicalterrorscale.org/ptsdata.php.

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-17-

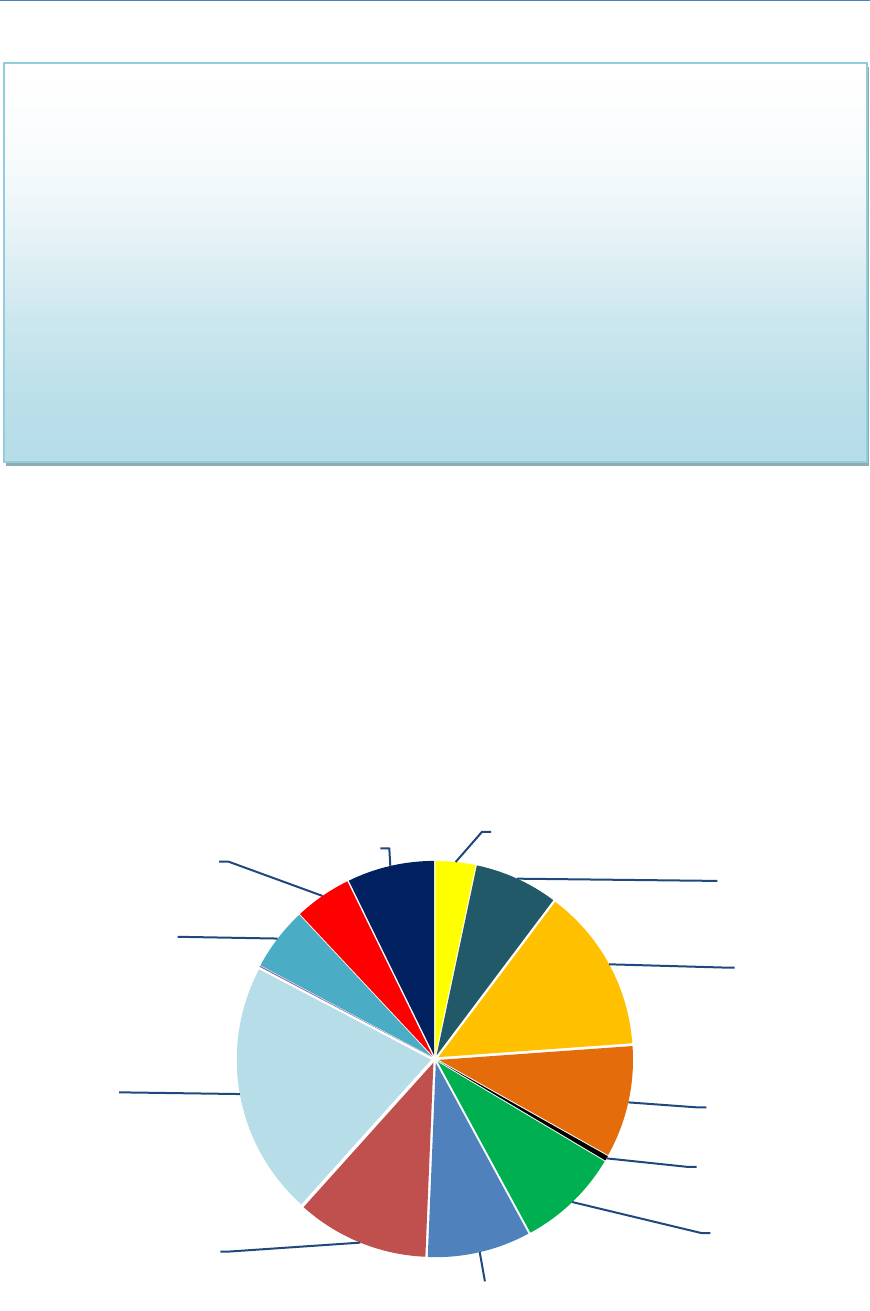

Figure 6: Representation of Interconnected Conflict Drivers in MENA

Sources: World Bank data

32. As the diagram above reflects, the socio-economic and political/governance factors work

in tandem and further fuelled or diminished by the subjective experience of the concerned

populations. For example, joblessness is not merely a monetary lack but can also be a source of

shame, humiliation, and exclusion. It raises concerns about marriage prospects among youth and

engenders a broader sense of not only economic fragmentation but also social isolation. The same

can be said in many respects of abuses by the state and its security services, which lead to not

only physical pain but a sense of betrayal and ever-present trepidation. Weak or illegitimate

regimes not only fail to meet expectations but stand as a constant source of frustration and as an

impediment to individuals‟ and societies‟ development, particularly when undermined by

rampant corruption and inequity.

Economic Dependence on Oil

and Gas Revenues (i.e., Rental

Dependence)

External Actors (e.g., Oil

Importers‟) Desire for Regional

Stability

Limited Non-State (civil society

or private sector) Models of

Good Governance

Limited Investments and Brain

Drain Hinder Job Growth &

Economic Diversification

Reliance on Security Services

to Discourage Opposition

Exclusion and Horizontal

Inequality (experienced as

humiliation and injustice)

Investment Flees, Increasing

Reliance on Extractive

Industries

Increased Securitization of the

State

Reduction of Voice and

Accountability, Increase in

Abuse by the State

Entrenchment of Initial Drivers of Conflict

Economic reliance on oil and gas is deepened, and private sector development is delayed

External actors re-emphasize need for regional stability and security

Opportunities for expression, including via civil society, are curtailed or forced underground

Governance is undermined, and state-citizenry divide widens

Governance Weaknesses

Limited institutional capacities and legitimacy

Constrained opportunities for citizen voice and accountability

Abuses of human rights and predation in the form of corruption

Limited and inadequate provision of common goods, including security, justice, and jobs

Outbreak of Opposition

May include protests, rebellion, terrorism, or other manifestations of opposition

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-18-

IV. THE WORLD BANK'S EXPERIENCE IN CONFLICT-AFFECTED

COUNTRIES IN MENA

33. Official development assistance (ODA) to MENA‟s fragile and conflict-affected states has

grown rapidly, with disbursements quadrupling from about US$6 billion in 2002 to nearly US$24

billion in 2008, primarily (though not exclusively) as a result of the conflict in Iraq.

61

Concurrently, civil society in the region has played an integral if somewhat under-recognized role

as social service providers, not least in areas most affected by insecurity. NGOs have played an

important role in service delivery in spite of generally having very close ties to the state. In

addition, Islamic charities are usually subject to more lax registration procedures and have been

able to use Zakat funds (almsgiving) to serve marginalized and vulnerable communities where the

state has often been absent.

62

34. The World Bank is one of many actors engaged in development assistance to conflict-

affected countries, working alongside other national and international development actors. The

World Bank‟s support has been guided by specific policies and procedures since 1998, as well as

dedicated staff and funding mechanism. The concept of “Low-Income Countries Under Stress”,

later superseded by the term “fragility”, was added to the agenda in 2001, thus enabling the

World Bank to move from its earlier “post-conflict” focus to a wider concern for conflict

prevention and risk reduction. Conflict and fragility are now seen as parts of a single agenda

aimed at increasing and refining the World Bank‟s support to peace building, state building and

governance.

63

The World Bank's experience in situations of conflict and fragility in MENA

35. This study focuses on those conflict-affected countries/territories in which the World

Bank has a lengthy record of assisting in the transition from violence to more peaceful forms of

dispute resolution. These include Iraq (which reentered the World Bank as client in 2004),

Lebanon, Yemen and the West Bank and Gaza.

64

The World Bank channeled almost US$5 billion

to these four countries/territories between 1998 and 2010,

65

an amount which comprised

approximately 490 lending, analytical and advisory activities. While only 177 of these activities

were lending operations, they accounted for US$4.7 billion of the US$5 billion spent.

66

Almost

70 percent of this amount was in the form of loans, while the remaining 30 percent were grants

61

Zyck and Barakat, “Development Assistance to the MENA Region‟s Zones of Conflict and Fragility”, background

paper to the World Bank Study on Conflict and Fragility in the MNA Region, 2010.

62

El Horr, “Civil Society in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Contexts in MENA: the emergence of NGOs and Islamic

Charities”, background paper to the World Bank Study on Conflict and Fragility in the MNA Region, 2010.

63

Re. description of OPCFC‟s mandate and as expressed by President Zoellick in his speech “Securing Development”

64

Algeria has also been affected by conflict and fragility in the period covered, it did however, not have an active

World Bank portfolio and has therefore not been included in this review.

65

Based on a portfolio review covering the calendar years 1998-2010. In World Bank terms this entails 14 fiscal years

FY97-FY11.

66

This figure includes funds from the International Development Association (IDA), from the International Bank for

Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), and from both global and country-specific trust funds

Reducing Conflict Risk: Conflict, Fragility and Development in MNA

-19-

coming from 13 different trust funds, a majority of which were country specific for the West

Bank and Gaza, and Iraq.

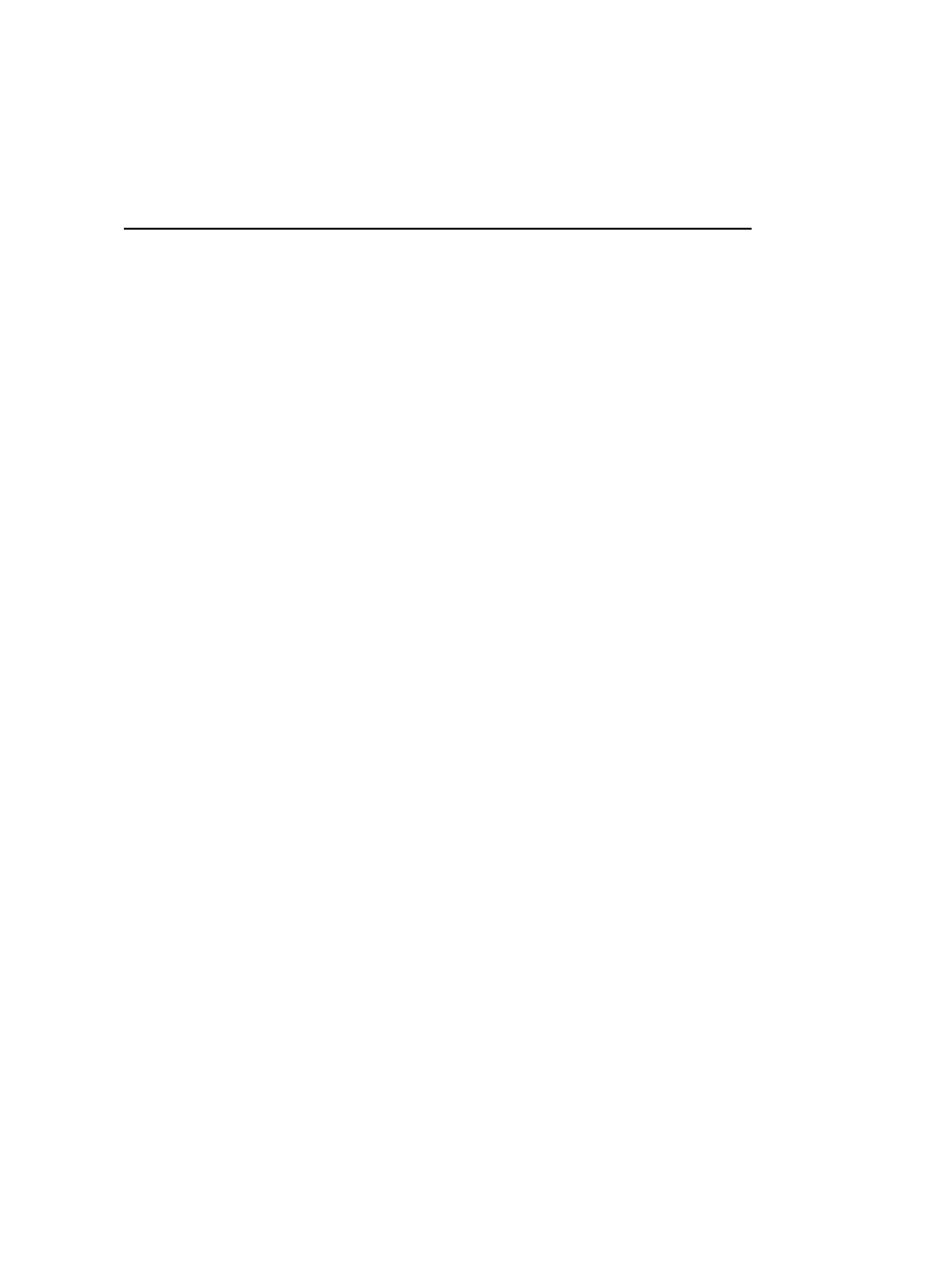

Figure 7: World Bank lending per source of funding

Source: World Bank data

36. The Bank‟s experience and traditional comparative advantage in poverty reduction and

development has led it to prioritize the mitigation of development related impacts of conflict and

fragility over the drivers of conflict.

67

World Bank activities have therefore also tended to be

reactionary in nature, with financing peaking in the periods after major security incidents.