CENTER FOR INSURANCE

POLICY AND RESEARCH

Extreme

Weather and

Property

Insurance:

Consumer

Views

July

Contents

Overview

Survey Methods

Demographics

Insurance Details

Extreme Weather and Insurance

Extreme Weather Beliefs and Insurance Action

Climate Risk Disclosures

Six Americas Segmentation

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

Executive Summary

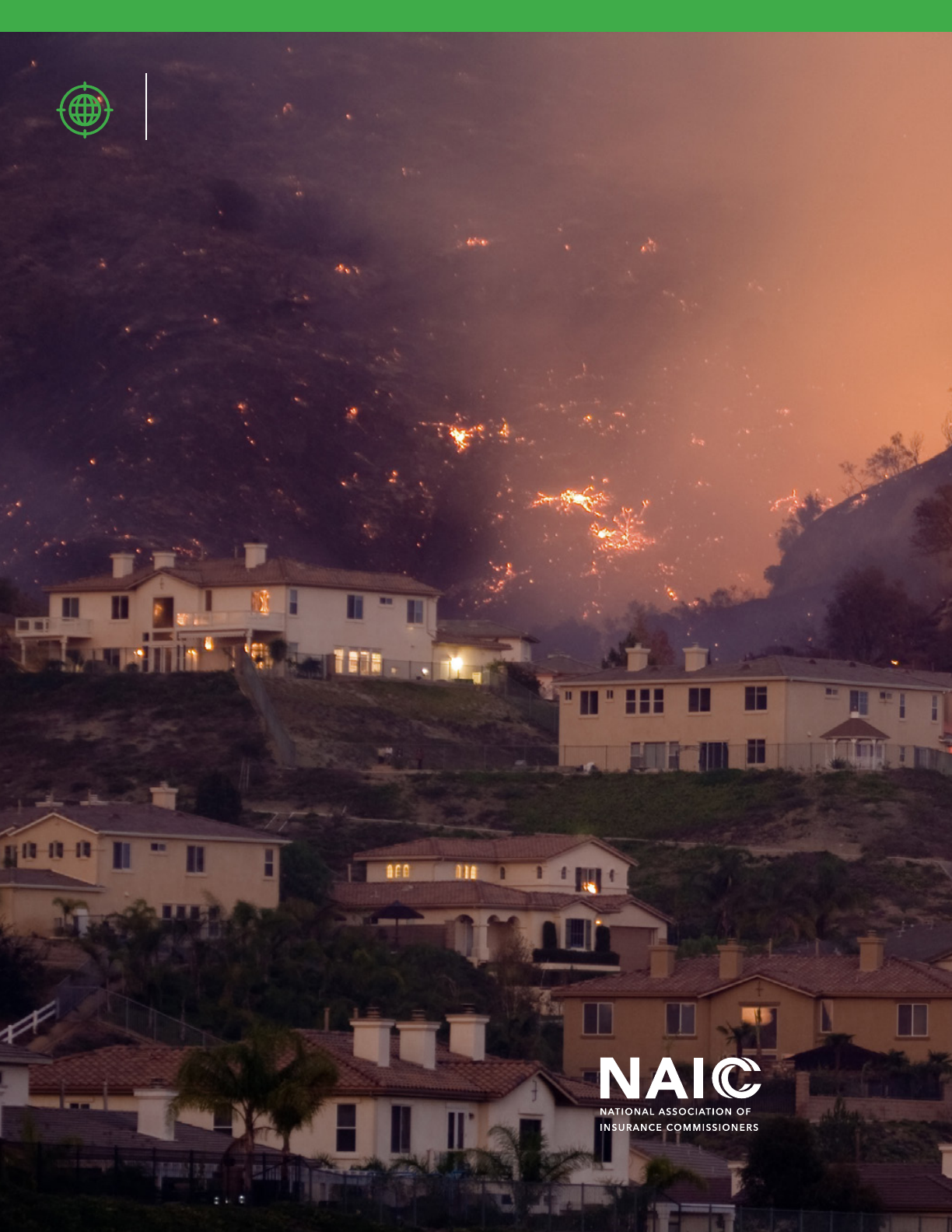

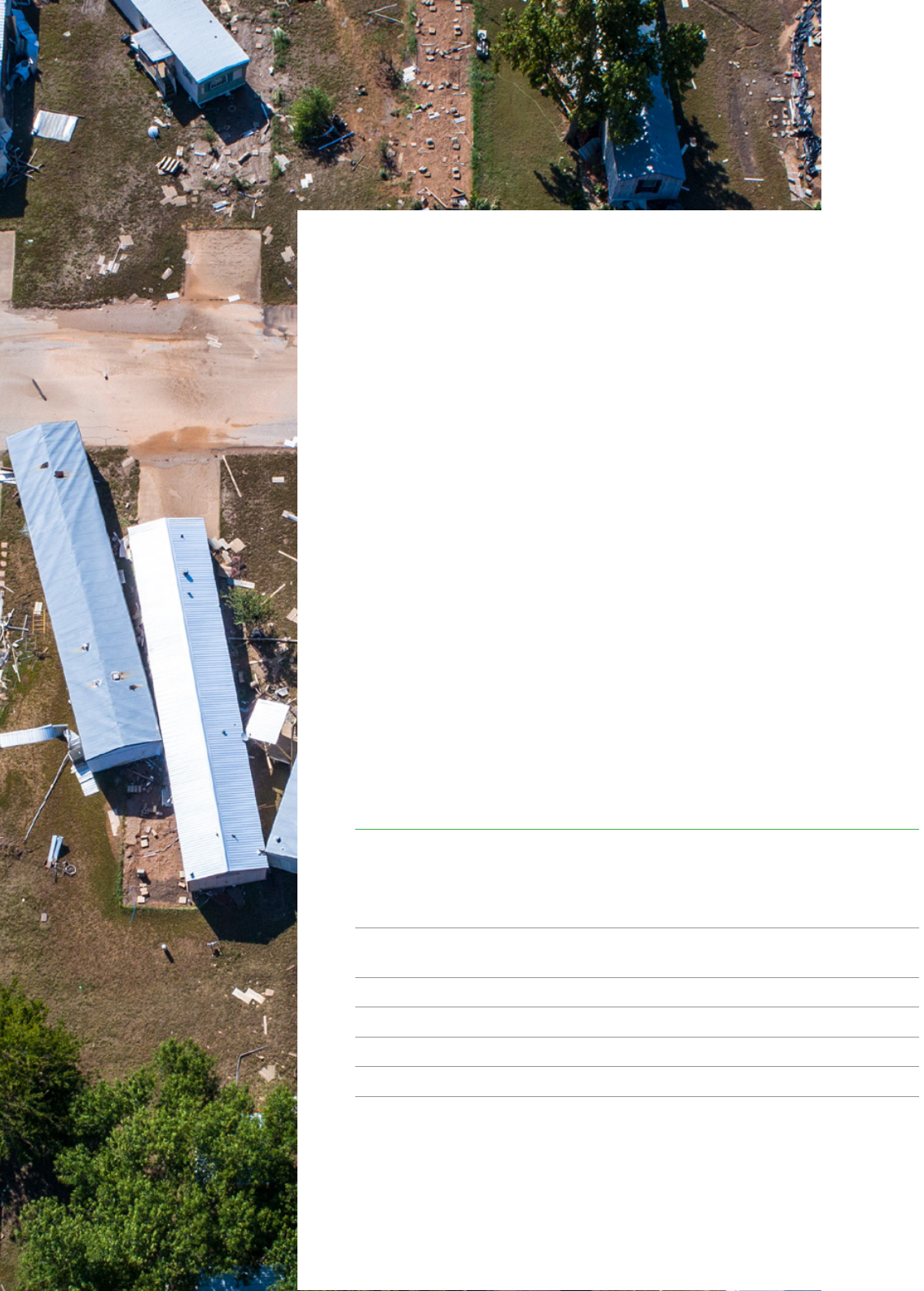

Homeowners face significant impacts to their property from escalating

extreme weather amplified by potential climate impacts. As roughly %

of homeowners have homeowners insurance,

1

the rising likelihood of

extreme and catastrophic weather events makes monitoring the frequency

and impact of natural disasters a critical insurance regulatory function. This

makes climate change/natural catastrophe risk and resiliency a key strategic

priority of the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC).

To help guide NAIC efforts in this domain (e.g., consumer outreach), this

study sought to better understand how homeowners are making the

connection between extreme weather events and their insurance coverage.

Specifically, we looked at three main questions:

) To what extent do respondents see a connection between extreme

weather events and their broader insurance coverage?

) What is the relationship between what respondents believe about

extreme weather and what actions they have taken related to their

homeowners insurance?

) How are homeowners segmented by their climate risk perceptions,

which further depend on loss experience and insurance coverage?

We surveyed , U.S. homeowners from age to over in every

U.S. state and Washington, DC. Respondents were recruited through

SurveyMonkey’s Audience panel. The survey was conducted March –,

.

Overall, we find that:

·

Most homeowners in our survey do, in fact, have homeowners

insurance, though respondents making less than $, a year

were % less likely to have a policy than others with higher incomes.

Affordability issues were the most prevalent factor indicated for not

having coverage.

NAIC Dwelling Fire, Homeowners Owner Occupied, and Homeowners Tenant and

Condominium/Cooperative Unit Owner’s Insurance Report (). Accessed May , at

https://content.naic.org/sites/default/files/publication-hmr-zu-homeowners-report.pdf.

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

·

A majority (%) believe their homeowners policy covers flood, even

though flood is not covered under standard policies and only about

% of homeowners actually have flood insurance.

·

Two-thirds of respondents said their homeowners insurance costs

have gone up over the past three years, with “increase in natural

disasters such as hurricanes and wildfires” indicated as a key reason

believed to be driving the increase.

·

People living in Pacific, West South Central and Middle Atlantic

2

states

are most likely to report trouble getting or renewing homeowners

insurance due to an increase in natural disasters. Across all premium

levels, homeowners paying more for their insurance report

increasingly higher levels of trouble renewing insurance because of

wildfires or hurricanes.

·

More than two-thirds of respondents said they were aware of things

they could do to protect their property from extreme weather events to

reduce their risk, but this awareness does not necessarily translate into

action. Only half had actually made changes, though more than three-

quarters said they would spend their own money to fortify their home in

exchange for a reduction in their homeowners insurance premium.

·

Four out of five homeowners expressed interest in knowing what

insurance companies are doing to address changing weather patterns

and other climate-related risks.

·

Homeowners revealed conflicting attitudes about climate-related

hazard risk. While many respondents indicated reluctance to move

to areas with flooding, hurricanes or wildfires and % think extreme

weather events are happening more frequently overall because of

climate change, on average they believe the area where they live

is slightly less vulnerable to extreme weather events than the U.S.

average.

·

Survey respondents demonstrated a high level of worry related to

climate change, with % of respondents classified as “alarmed,” more

than double the national average.

·

Those having trouble obtaining homeowners insurance consistently

indicate being alarmed about climate change.

This report provides an overview of the survey methodology along with

brief findings from the survey responses.

For more information, please contact Lisa Groshong

at [email protected]g.

Lisa Groshong, Ph.D.

Communication Research Scientist

Tyler Gerson

Research Assistant

Jeffrey Czajkowski, Ph.D.

Director

Juan Zhang, Ph.D.

Postdoctoral Research Associate

Laura Kane

Communications Director

Jennifer Gardner

Data Coordination and Statistical

Analysis Manager

Pacific: Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon and Washington; West South Central: Arkansas,

Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas; Middle Atlantic: New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania

CIPR

NAIC

Disclaimer

This study represents the opinions

of the authors and is the product

of professional research. It is not

intended to represent the position or

opinions of the NAIC or its members,

nor is it the official position of any

NAIC staff members. Any errors are

the responsibility of the authors.

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

Survey Methods

The extreme weather and property insurance survey was conducted March

–, , using a nonprobability sample of , U.S. homeowners

recruited through SurveyMonkey’s Audience panel. SurveyMonkey

calculated a margin of sampling error on the total results as +/– percentage

points at a % confidence level.

SurveyMonkey targeted respondents in their panel who previously identified

themselves as homeowners when asked, “Do you rent or own the place

where you live?” SurveyMonkey’s methodology does not distinguish

between stand-alone houses, condos, apartments, or other types of homes.

The survey’s questions explored experiences, knowledge and perceptions

related to property insurance among homeowners. Participants were asked

to answer questions about their home insurance, including their role in

choosing it, the approximate cost, and whether the price has changed.

Participants were asked about their experience with home damage due

to extreme events, whether they have altered or would alter their home to

protect it, and if they believe their insurance costs have changed due to

such events. The survey also queried their interest in insurance companies’

actions to address climate change. Demographic information included age,

gender, race, annual household income, and U.S. Census Bureau region.

Audience segmentation questions were drawn from Global Warming’s Six

Americas Super Short Survey (SASSY!), an audience segmentation tool

designed to cluster respondents according to their climate views.

3

Breanne Chryst, Jennifer Marlon, Sander van der Linden, Anthony Leiserowitz, Edward

Maibach and Connie Roser-Renouf (). Global Warming’s “Six Americas Short Survey”:

Audience Segmentation of Climate Change Views Using a Four Question Instrument,

Environmental Communication, :, –, DOI: ./...

The survey also queried their

interest in insurance companies’

actions to address climate change.

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

Survey Results

Demographics

Participants were targeted to capture a balanced distribution of homeowners

across gender and age according to U.S. Census data (U.S. Census Bureau

). The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that as of , about % of

households owned their own home.

4

Table presents the demographics of participants. Slightly less than one-

half of the respondents were women (%). Women tend to be slightly

overrepresented in surveys, but SurveyMonkey had trouble recruiting

enough eligible older female homeowners to balance this segment of the

sample. We suspect that limiting survey participation to homeowners may

have influenced the gender balance of our sample.

The sample was evenly split between participants under and over the age

of . The age distribution differs from the general U.S. population because

we limited our survey to participants over the age of . Approximately

% of the respondents’ households reported earning less than $,.

This is less than the general U.S. population, possibly because people with

lower incomes are less likely to own their own homes.

About % of the respondents came from the Northeast, Midwest and

West, with about twice that many (.%) from the South. Every U.S. state

and Washington, DC, were represented.

The U.S. Census Bureau estimates

that as of , about % of

households owned their own home.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau. Accessed May , , at https://www.census.gov/newsroom/

press-releases//homeownership.html.

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

Table . Survey Demographics

Respondent Demographics (n = ,) N

% of Survey

Participants

% of U.S.

Population

Gender (n = ,)

Female 1,177 47.4 50.8

5

Male 1,304 52.6 49.2

Age (n = ,)

18–29 291 11.7 13.6+

6

30

–44 947 38.2 19.5

45

–60 662 26.7 18.9

>60 581 23.4 22.8

Household Income (n = ,)

$0–$49,999 594 23.9 38.4

7

$50,000

–$74,999 363 14.6 17.4

$75,000

–$99,999 383 15.4 12.8

$100,000+ 949 38.3 31.4

Prefer Not to Answer 192 7.7

U.S. Census Region (n = ,)

Northeast (includes Middle Atlantic

and New England states) 514 20.8 17.1

8

Midwest (includes East and

West North Central states) 522 21.1 20.8

South (includes East and West South

Central and South Atlantic states) 929 37.6 38.3

West (includes Mountain and

Pacific states) 506 20.5 23.9

Race (n = ,)

9

White 2,163 87.0 72.0

Black 167 6.7 12.8

Asian 103 4.1 5.7

American Indian or Alaska Native 41 1.7 0.9

Native Hawaiian or Other

Pacific Islander 9 0.4 0.2

Other 59 2.4 5.0

10

Source: U.S. Census Bureau.

Accessed May , , at

https://data.census.gov/

cedsci/table?q=United%

States&tid=ACSSTY.S.

U.S. Census groups ages –, so

this table includes people aged

– but excludes those –.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau.

Accessed May , , at

https://data.census.gov/

cedsci/table?q=household%

income&tid=ACSSTY.S.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau.

Accessed May , , at https://

www.census.gov/popclock/print.

php?component=growth&image=//

www.census.gov/popclock/share/

images/growth_.png.

Total exceeds % because

respondents could choose more

than one option.

In addition, .% of the U.S.

population identifies with two or

more races.

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

Insurance Details

In addition to basic demographics, we examined whether consumers have

homeowners insurance and how much they currently pay for that insurance.

We also asked a knowledge question that investigated whether consumers

understood that their homeowners insurance policy most likely did not

include flood coverage.

Homeowners Insurance

The vast majority of respondents (%) reported having a homeowners

insurance policy, though this varied by income. Only % of respondents

with household incomes of less than $, reported having a policy,

as opposed to % of respondents with household incomes of $,

or more. Geographic differences also emerged, with the lowest levels of

homeowners insurance among respondents from East South Central (%)

and West South Central (%). Regions with the highest rates of homeowners

insurance include New England (%) and Pacific (%).

The respondents who replied “no” were asked, “What is the main reason

you do not have homeowners insurance?” Among this small group, the

most common answer was that it’s too expensive.

Cost is the most common reason homeowners

do not have insurance.

It’s too expensive. 43.7% 66

I don’t need it because my

home is paid o.

20.5% 31

I am not required to have it. 11.3% 17

I self-insure. 8.6% 13

I don’t trust insurance companies. 8.0% 12

Other (please specify) 8.0% 12

Most respondents (%) reported being the sole decision-maker in choosing

their homeowners insurance, though there were differences between men

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

and women. While % of men said they were the sole decision-maker,

only % of women said they were.

Price of Insurance

As of , the average annual premium for homeowners insurance covering

a home valued at $, to $, is estimated to be $ to $,.

11

Numerous factors influence the cost of homeowners insurance, most

notably real estate values and exposure to risks, such as flood, earthquake

or tornado.

More than half of consumers pay $, or

less for their homeowners insurance.

Annual Premium for Homeowners Insurance

Response

Percent Responses

Less than $1,000 per year 21.8% 508

Between $1,000 and $2,000 per year 39.8% 928

Between $2,001 and $4,000 per year 21.0% 489

More than $4,000 per year 9.5% 221

I don’t know 8.0% 186

Total 2,332

Consistent with our expectations, respondents’ reported insurance

premiums were correlated with income, suggesting that those with higher

incomes own more expensive houses that cost more to insure. More than

two-thirds (%) of respondents with income over $, reported

paying more than $, for their insurance, with % of those paying more

than $, a year. In contrast, more than half of homeowners earning

less than $, paid less than $, for their homeowners insurance.

The regions reporting the highest premiums were the Middle Atlantic (New

Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania) and West South Central (Arkansas,

Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas). Respondents in East South Central

(Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi and Tennessee) reported the lowest overall

premiums.

Flood

We asked respondents, “Is flood covered by your homeowners insurance?”

This was included as a knowledge question to test whether people are

NAIC (). Dwelling Fire, Homeowners Owner-Occupied, and Homeowners Tenant and

Condominium/Cooperative Unit Owner’s Insurance Report: Data for . Accessed online

at https://www.naic.org/prod_serv/HMR-ZU-.pdf.

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

aware that flood insurance must be obtained through a separate policy

or if they believe their regular policy covers it.

More than half of respondents (%) indicated that they believe their

homeowners policy covers flood, though regional differences emerged.

Respondents in New England were least likely to answer “yes” (%),

followed by West North Central (%) and Mountain (%). Respondents

were most likely to answer “yes” in West South Central (%), Middle Atlantic

(%), Pacific (%) and South Atlantic (%). In a survey conducted by

the NAIC in that made it more clear flood was not covered under

standard policies, only % of homeowners indicated they had purchased

flood insurance.

Standard homeowners insurance policies exclude flood damage, so

homeowners must purchase separate policies, either through private

companies or the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), which is

operated by the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

Based on FEMA and U.S. Census estimates,

12

only about .% of

homeowners actually have flood insurance.

To what extent do consumers see a connection

between extreme weather events and their broader

insurance coverage?

For this question, we examined whether consumers’ homeowners insurance

costs have gone up and what consumers believe prompted those increases.

We also asked whether homeowners have had trouble getting or retaining

their insurance and what they perceive to be the most pressing threats

facing their property.

Rising Costs

Among homeowners who have lived in the same house for the past three

years, % report that their premium has gone up either a little bit (%)

or significantly (%). Only % said the premium has gone down. The

remainder report that the premium has not changed (%) or that they do

not know (%).

Homeowners whose premiums went up were asked what they thought

was the most likely reason. The most common response was “insurance

companies trying to increase profits,” followed closely by “increase in

natural disasters such as hurricanes and wildfires.”

As of , there were ,, flood insurance policies in force among ,,

housing units.

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

Consumers cite a variety of reasons for why

they believe their premiums went up.

% Responses

Insurance companies trying to increase profits 26% 405

Increase in natural disasters such as hurricanes

and wildfires

26% 397

Increase in home value 23% 363

Changes to coverage 21% 328

Made a claim recently 4% 55

Total 1,548

Trouble Obtaining or Renewing Coverage

Among the respondents who believe their premium has gone up

because of an increase in natural disasters, about half (%) said they have

had trouble getting or renewing homeowners insurance because of natural

disasters, compared with less than one-third of respondents (%) overall.

People who pay higher premiums for their homeowners

insurance are more likely to have trouble getting or

renewing insurance because of wildfires or hurricanes.

Yes % No %

Less than $1,000 14% 86%

$1,000

–2,000 22% 78%

$2,001

–4,000 41% 59%

$4,000 or more 66% 34%

Across the entire sample, homeowners paying higher premiums had

statistically significantly more trouble getting or renewing insurance because

of natural disasters (% confidence level, p = .).

Notable geographic differences emerged related to this question. More

than one-third of respondents in Pacific (%; Alaska, California, Hawaii,

Oregon and Washington), West South Central (%; Arkansas, Louisiana,

Oklahoma and Texas) and Middle Atlantic (%; New Jersey, New York and

Pennsylvania) states reported challenges in getting or renewing homeowners

insurance because of natural disasters, while few respondents did in New

England (%; Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

Island and Vermont), East South Central (%; Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi

and Tennessee) and Mountain (%; Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana,

New Mexico, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming) states.

Threats

Survey respondents cited several top property threats facing their homes.

Across the entire sample, nearly one-third (%) believed that the top threat

was weather-related water damage, such as rain, melting ice or snow. About

one-quarter (%) saw wind damage from a tornado or hurricane as the

top threat. About % cited non-weather-related water damage, such as

plumbing or appliance issues. Less-frequent choices included earthquake

(%), theft (%), hail (%) and wildfire (%). A majority of homeowners

identified weather-related threats, such as water damage, hail, wind damage

and wildfire, as the most significant threats facing their homes-- except in

the West, where earthquake was identified as the top threat.

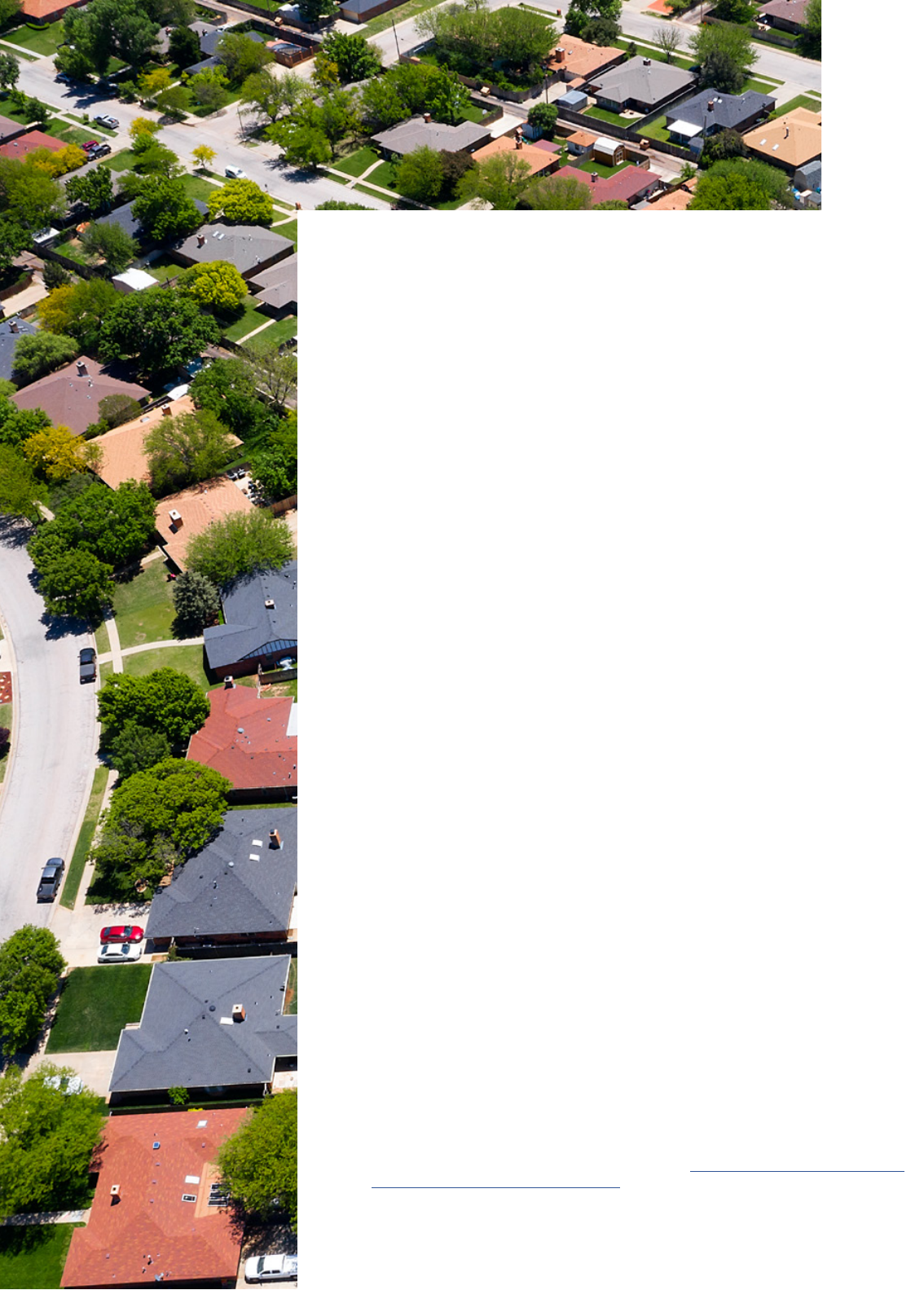

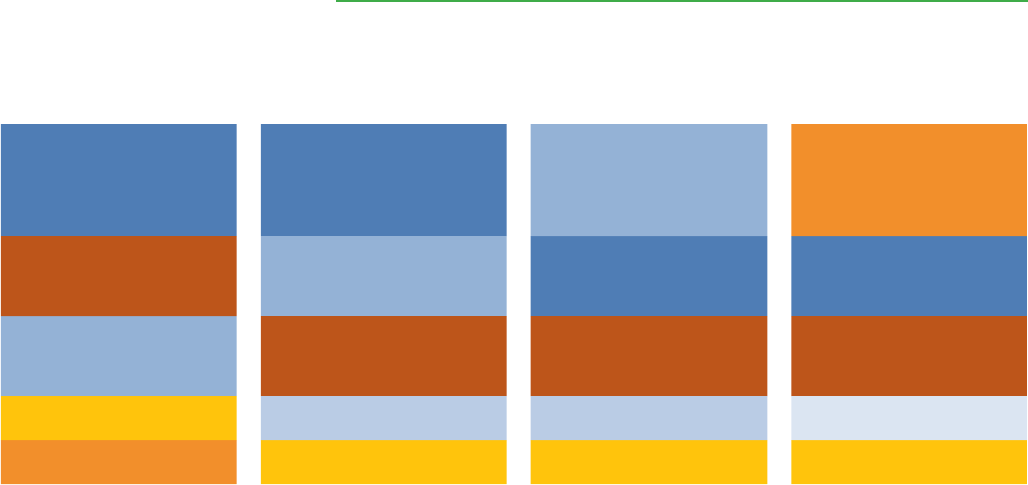

Weather-related versus non-weather-related property threats

perceived by American homeowners, by U.S. Census Region

Survey question: What would you say is the most significant property threat facing your home?

Source: NAIC’s consumer homeowner property insurance survey, conducted March -, ,

with , adults nationwide.

West

South

Midwest

Northeast

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Weather-related Non-weather-related

Water damage—weather related

Wind damage—tornado/hurricane

Hail

Wildfire

Water damage—plumbing/appliance

Earthquake

Theft

Other

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

Top threat perceptions varied dramatically by region. For example, weather-

related water damage, such as rain, melting ice or snow, was especially

salient in New England, where % of respondents cited it as their most

significant property threat. This threat was also rated as higher than average

in the Middle Atlantic (%) and East North Central (%). Similarly, while

one-quarter of respondents overall cited wind damage as the biggest

threat, this number was far higher in East South Central (%), South Atlantic

(%) and West North Central (%). While only % of respondents overall

saw earthquake as their most significant threat, % of respondents in the

Mountain region chose it. It was also higher than average in the Middle

Atlantic (%), New England, East South Central and South Atlantic regions,

cited by about % of respondents in each. Hail was far higher than average

in West North Central (%) and Mountain (%) states.

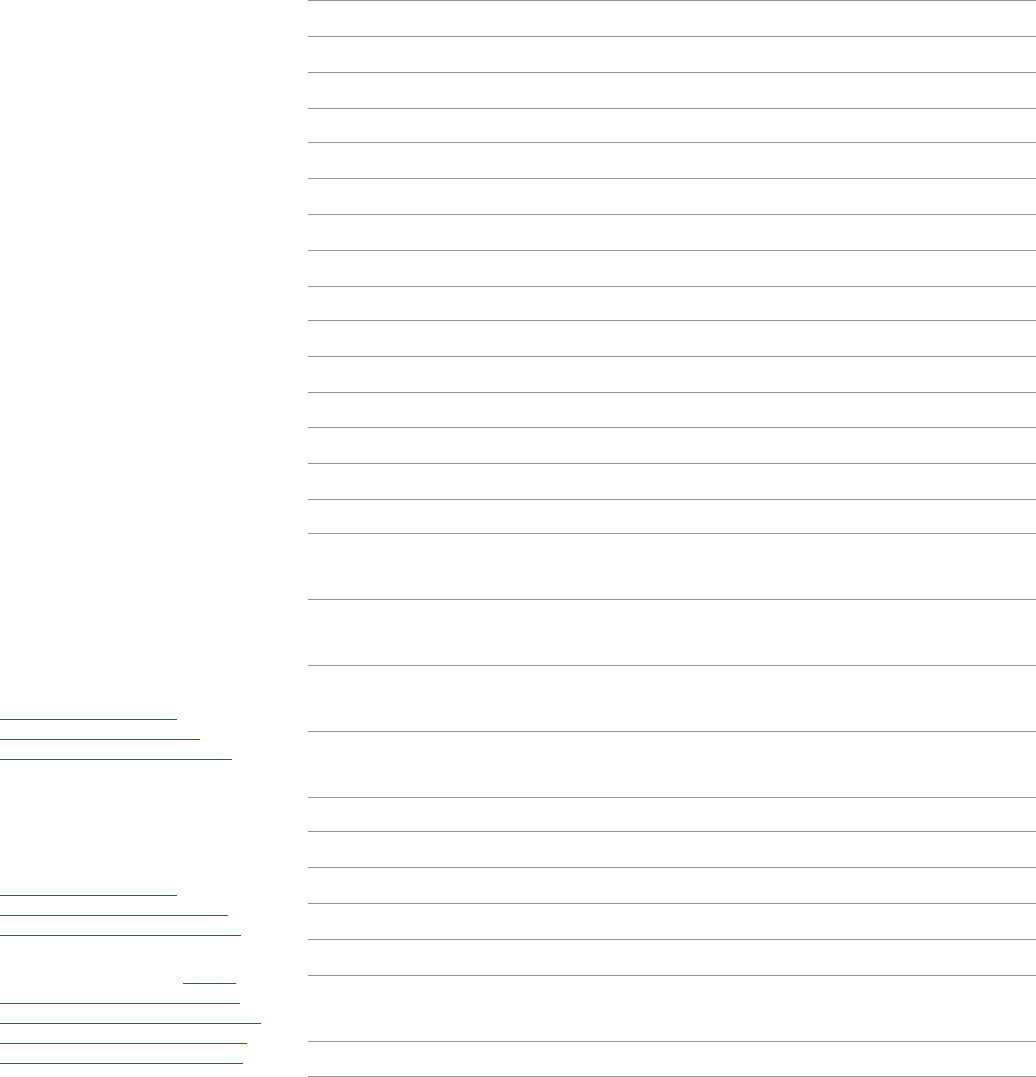

Top property threats perceived by American

homeowners vary by U.S. Census Region

Survey question: What would you say is the most significant property threat facing your home?

Source: NAIC’s consumer homeowner property insurance survey, conducted March -, ,

with , adults nationwide.

Northeast Midwest South West

39%

Weather-

related water

damage

32%

Weather-

related water

damage

35%

Wind damage

—tornado or

hurricane

23%

Earthquake

20%

Water damage

—plumbing/

appliance

27%

Wind damage

—tornado or

hurricane

25%

Weather-

related water

damage

19%

Weather-

related water

damage

17%

Wind damage

—tornado or

hurricane

15%

Water damage

—plumbing/

appliance

16%

Water damage

—plumbing/

appliance

18%

Water damage

—plumbing/

appliance

10%

The

10%

Hail

7%

Hail

13%

Wildre

6%

Earthquake

8%

The

7%

The

10%

The

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

What is the relationship between what consumers believe

about extreme weather and what actions they have taken

related to their homeowners insurance?

To explore this question, we looked at whether homeowners report being

aware of ways to protect their property and asked if they had taken steps to

do so. We also asked about their experience with threats to their property

and whether they would move somewhere that faced certain types of risks.

Respondents were asked to rate the vulnerability of their location and

consider whether extreme events are becoming more frequent. Finally, we

asked whether they would visit a website where they could learn about how

their insurance company is assessing and managing climate-related risks.

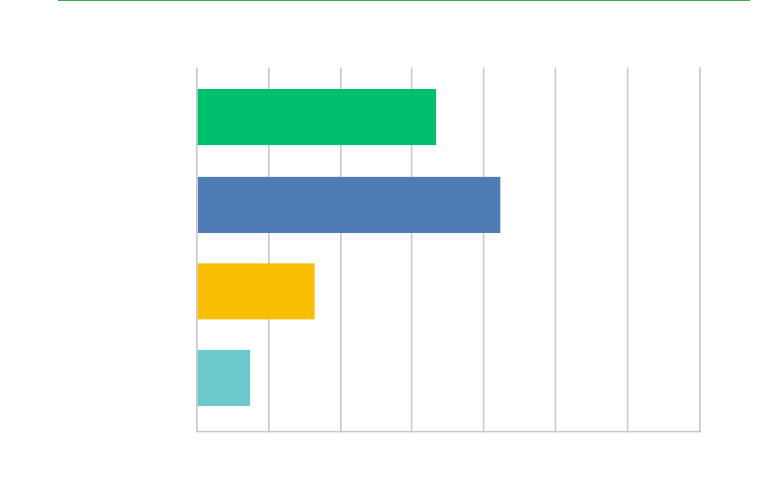

Actions to Protect Property

Most respondents overall (%) said they were aware of things they could do

to protect their property from extreme weather events to reduce their risk;

this represents % of men and % of women. However, this awareness

does not necessarily translate into action. Only half (%) of respondents

had actually made changes to their homes, though more than three-quarters

(%) said they would be willing to spend their own money to fortify their

home in exchange for a reduction in their homeowners insurance premium.

Many respondents (%) indicated they would be willing to spend between

$ and $, for a % to % premium reduction, suggesting that

homeowner willingness to invest in protective home improvements may

depend on perceived return on that investment.

Homeowners would invest up to $, in home protection

Up to $500

Between $501

and $2,500

Between $2,501

and $5,000

More than

$5,000

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70%

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

Perceptions of Future Loss Risk

Homeowners were asked if they believe recent weather events have affected

their risk of future losses to their home or property. About equal numbers

of respondents answered “yes” (%) and “no” (%), though another %

said they were not sure.

Respondents’ perception of risk seems to be growing. Using a slider bar

with values ranging from to , with being “extremely low risk,”

being “moderate risk” and being “extremely high risk,” participants

were asked to rate the level of risk they believe their property faced from

extreme weather events five years ago, today and five years from now.

Mean level of concern increased from five years ago to related to

today and looking into the future.

Risky Living

The majority of respondents (%) said they would not move to an area

that has experienced flooding or hurricanes, while even more (%) would

be reluctant to move to an area that has experienced wildfires. Women

were far less willing to move to an area with flooding or hurricanes (%

of women versus % of men said “yes”) or that had experienced wildfires

(% of women versus % of men said “yes”).

This is in line with recent research by the real estate website Redfin,

13

which

found that more than three-fourths (%) of Americans would hesitate

before buying a home in an area with increasing frequency or intensity of

natural disasters. Similar percentages would be hesitant about buying in

areas with extreme temperatures (%) or rising sea levels (%).

Risk Assessment: Worse Elsewhere but Extreme

Weather Events are More Frequent

On the whole, respondents seem to consider the area where they live

slightly less vulnerable to extreme weather events than the U.S. average. On

a scale of to , with being “extremely low risk,” being “moderate

risk” and being “extremely high risk,” the mean response was , just

below average.

Despite believing that their own area is less vulnerable to extreme events,

three-quarters (%) of respondents believe that extreme weather events

are happening more frequently overall because of climate change. There

was no significant difference between men and women. Again, the mean

Katz, Lily (). “Nearly Half of Americans Who Plan to Move Say Natural Disasters, Extreme

Temperatures Factored into Their Decision to Relocate: Survey.” Accessed May , , at

https://www.redfin.com/news/climate-change-migration-survey/.

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

response to the question “To what extent do you think climate change has

impacted the risks to your home?” was just below half, a mean response of

on a -point scale from “extremely low risk” to “extremely high risk.”

Insurer Climate Risk Disclosures

Homeowners were asked to imagine there was a website where they could

find out what insurance companies are doing to address changing weather

patterns and other climate-related risks.

Most respondents (%) indicated they would visit this website. The ,

respondents who answered “yes” were asked to what extent they would

use this information to decide which insurance company they do business

with. On a scale of to , with being “not at all” to being “a great

deal,” the median response was , and the mean was roughly . This

suggests that consumers would use this information to a moderate amount.

Most respondents said they would visit a website to find out

how insurance companies are addressing climate risks.

Information about insurer climate assessment and management is, in fact,

currently available on the California Department of Insurance (DOI) website.

This information is based on the Insurer Climate Risk Disclosure Survey,

which the NAIC adopted in . Currently, about , companies provide

information about their climate risk governance, climate risk management,

Yes

No

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

modeling and analytics, stakeholder engagement, and greenhouse gas

management. In , the CIPR released a report examining how insurers

across key characteristics assess and manage climate risks and how their

responses have changed over time.

The NAIC’s Climate and Resiliency (EX) Task Force, formed in , has been

charged with coordinating the organization’s domestic and international

efforts on climate-related risk and resiliency issues, including dialogue

among state insurance regulators and with industry, consumers and other

stakeholders.

How are homeowners segmented by their climate risk

perceptions, which may depend on loss experience, and

insurance coverage?

To explore this question, we have included a brief overview of audience

segmentation based on perception of climate change, constructed using

a validated survey instrument developed by researchers at Yale. We have

also included respondents’ personal experience with hazards.

Global Warming’s Six Americas

We used the Yale Program of Climate Change Communication and the

George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication’s

SASSY! Group tool

14

to analyze how our survey respondents compare to

the national average in terms of their global warming beliefs, behaviors,

and policy preferences. Using national samples and machine learning

algorithms, the Yale group identified a subset of four salient questions

from an original set of questions.

The SASSY! framework uses these questions to investigate respondents’

climate perceptions:

) How important is the issue of global warming to you personally?

) How worried are you about global warming?

) How much do you think global warming will harm you personally?

) How much do you think global warming will harm future generations

of people?

Breanne Chryst, Jennifer Marlon, Sander van der Linden, Anthony Leiserowitz, Edward

Maibach and Connie Roser-Renouf (). Global Warming’s “Six Americas Short Survey:”

Audience Segmentation of Climate Change Views Using a Four Question Instrument,

Environmental Communication, :, –-, DOI: ./...

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

Using responses to these questions, the Yale group

identified six audience segments:

·

Alarmed: Those convinced global warming is happening, human-

caused, and an urgent threat. These people strongly support climate

policies.

·

Concerned:They think human-caused global warming is occurring

and that it carries a serious threat, yet they tend to believe that climate

impacts are still distant in time and space. Thus, climate change

remains a lower priority issue.

·

Cautious:Those who have not yet made up their minds.

·

Disengaged:Those who are largely ignorant about global warming.

·

Doubtful:Those who do not think global warming is happening or

believe it is simply a natural cycle.

·

Dismissive:Those who believe global warming is not happening,

human-caused, or a threat, and who espouse conspiracy theories and

hoax claims.

The true accuracy rate for the model ranges from % to % across the

six segments.

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

Over recent years, the national distribution of the Six Americas has shifted

significantly. For example, between and , the “alarmed” category

rose from % to % of the U.S. adult population, while those categorized

as “dismissive” decreased from % to %. “Cautious” and “doubtful” have

also declined.

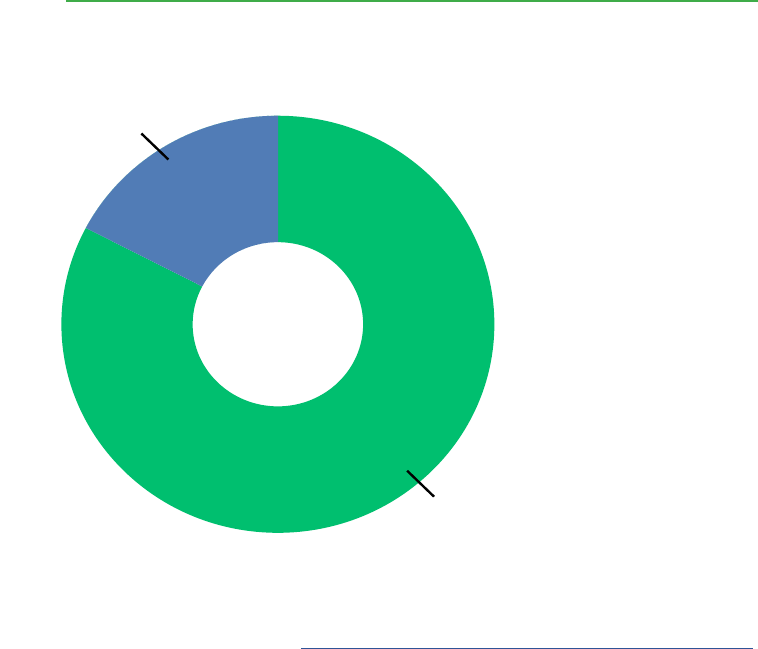

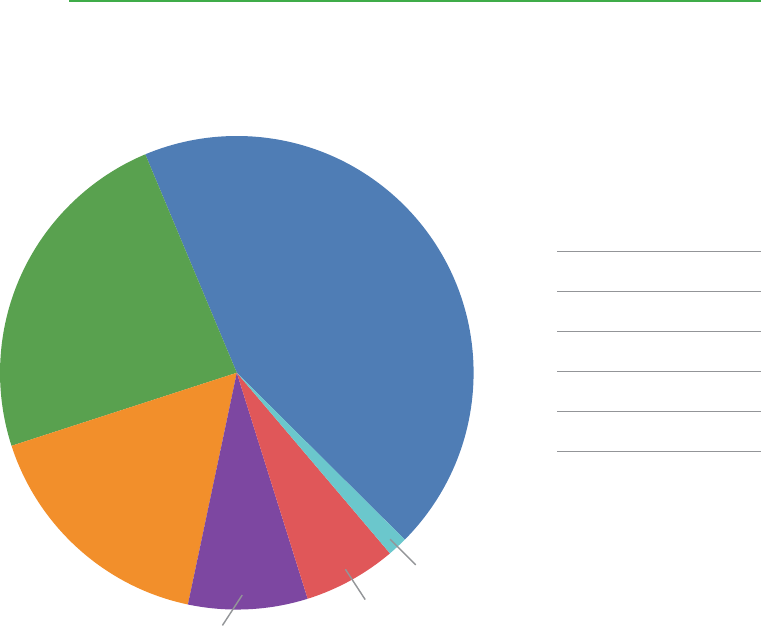

Six Americas audience segmentation classified

more than two-thirds of survey respondents as

“alarmed” or “concerned” about climate change.

Respondents to our survey demonstrated a high level of alarm related

to climate change; % of the respondents in our sample were classified

as “alarmed,” about twice the national average. Meanwhile, the other

five groups were smaller than their national counterparts. Nationally, the

proportion of those classified as “alarmed” has been steadily growing over

the last five years, while the more skeptical segments have been declining.

However, our sample highlights an even stronger level of concern related

to climate change issues than the national average. Below is a comparison

of our sample’s segmentation to the national average.

We also analyzed the Six Americas audience segmentation across coastal

states by clustering our sample into five groups based on region. Instead

1085: Alarmed

579: Concerned

408: Cautious

32: Disengaged

203: Doubtful

158: Dismissive

Alarmed

.%

Concerned

23.5%

Cautious

16.6%

Disengaged

8.2%

Doubtful

6.4%

Dismissive

1.3%

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

of grouping states by U.S. Census region, the following analysis groups

states by coastal exposure, given that climate risk perception and loss

experience can vary substantially between coastal and non-coastal areas.

·

Pacific Coast: Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon and Washington

·

Gulf Coast: Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas

·

Atlantic Coast: Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Maine, Maryland,

New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Rhode Island,

South Carolina and Virginia

·

Great Lakes Coast:

15

Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio,

Pennsylvania and Wisconsin

·

Not Coast: All other states

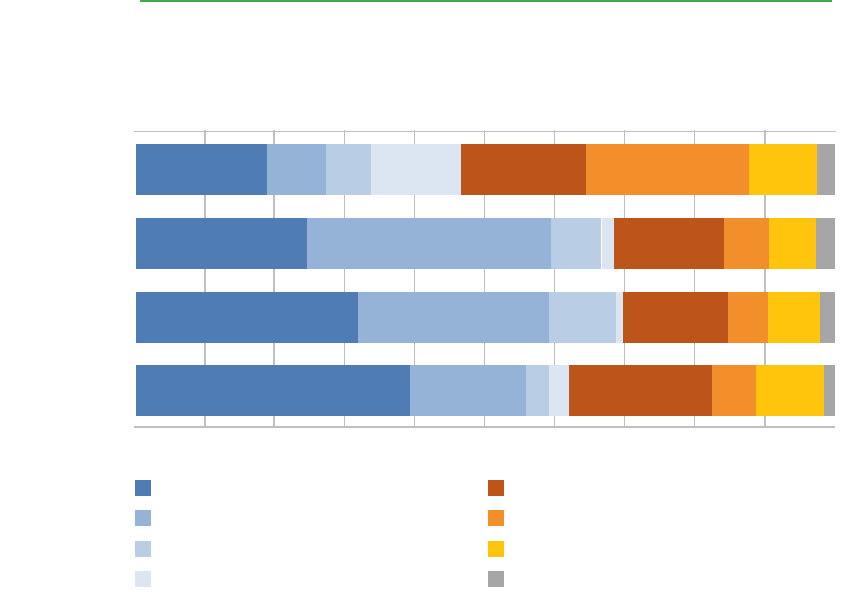

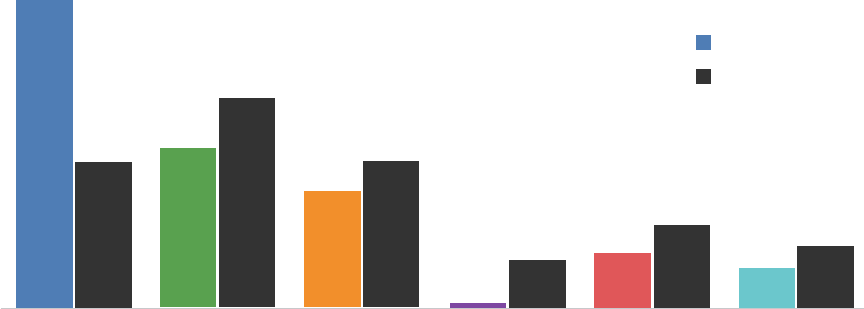

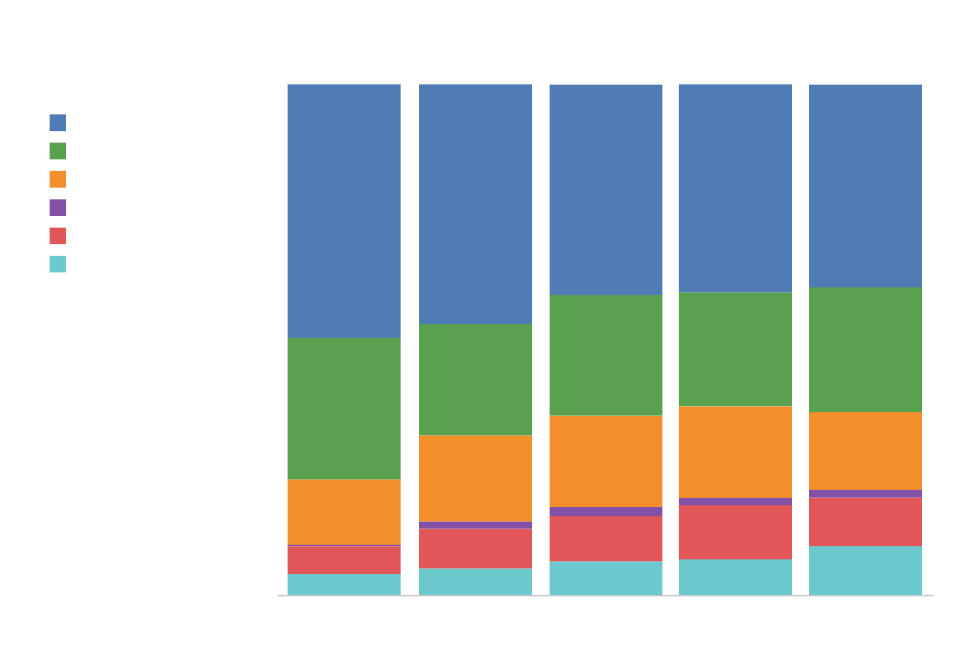

The aggregated bar chart shows the percent of respondents in each of

the Six Americas categories by coastal area. On average, respondents

from coastal states are more alarmed about the climate change risk than

those from non-coastal states. Half of the individuals in Pacific states (%)

were classified as alarmed, followed by % in Atlantic states. Fewer

alarmed individuals were found in Gulf Coast (%), Great Lakes (%),

and non-coastal (%) states. The differences between Pacific states and

non-coastal states and between Atlantic states and non-coastal states are

statistically significant. Respondents in Pacific states and Atlantic states are

also significantly less likely to be dismissive compared to those in non-

coastal states.

For our analysis, the Great Lakes Coast states are virtually not different from the Not Coast

states in terms of the climate change activities. However, we would like to stick to this

commonly used method to divide the geographical regions. Also, the Great Lakes Coast

may have more inland flooding than the Not Coast states.

1%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

Alarmed Concerned Cautious Disengaged Doubtful Dismissive

21%

40%

23%

30%

17%

21%

7%

6%

9%

8%

12%

Group Data vs. National Estimate (March 2018)

Group Data

National Estimate

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

Note: The asterisk (*) denotes a statistically significant difference compared to the

Not Coast states.

Our Six Americas audience segmentation groups survey respondents

based on their risk perceptions of climate change. Here, we examine

the relationship between climate risk perception and two factors: ) loss

experience; and ) the difficulty in obtaining homeowners insurance.

16

First- or Second-Hand Experience with Hazards

We asked whether respondents or someone they knew had suffered home

damage due to three common hazards: ) hurricane (HC); ) wildfire (WF);

and ) earthquake (EQ). As a respondent may answer “yes” to all three

questions, we divide our sample into seven exclusive groups: no loss

experience, loss experience of only one event (HC only, WF only, EQ only),

loss experience of only two events (HC & WF only, HC & EQ only, WF & EQ

only), and loss experience of all three types of events (HC & WF & EQ). On

average, % of respondents had no loss experience; % of respondents

had loss experience with all three events.

For further analysis, please refer to our academic manuscript, in which we further examine

how respondents’ climate risk perception varies across demographic, loss experience,

insurance, and other factors.

100%

80%

60%

40%

20%

0%

Pacific Ocean Atlantic Ocean Gulf Great Lakes Not

Coast Coast Coast Coast Coast

50%

*

5%

*

22%

24%

40%

24%

22%

20%

15%

18%

17%

9%

9%

9%

7%

10%

7%

8%

41%

41%

47%

*

Six Americas Segment by Coastal Area

4%

*

28%

13%

5%

*

SASSY Segment

Alarmed

Concerned

Cautious

Disengaged

Doubtful

Dismissive

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

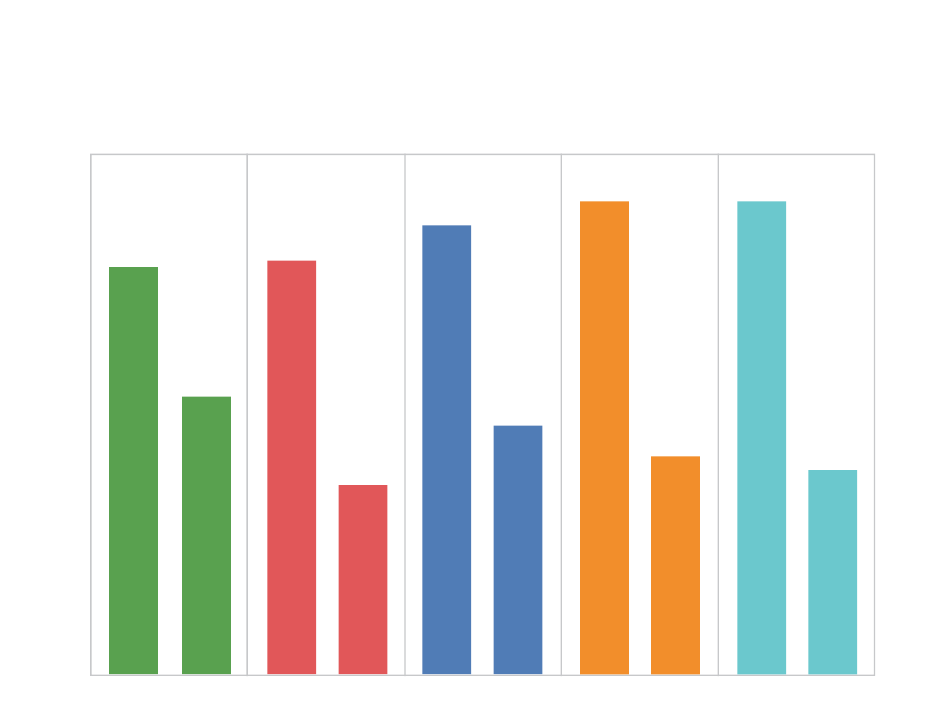

Six Americas Level by Loss Experience

Next, we show how the average percent of alarmed respondents varies

across loss experience. We specifically focus on the alarmed category

because it has the largest portion (%) in our sample, and only alarmed

individuals strongly support climate policies.

The chart below shows that only having hurricane experience does not

effectively increase individuals’ risk perceptions of climate change, even

in coastal states. For individuals who have had loss experience of both

hurricanes and wildfire, climate risk perceptions significantly increase (except

Great Lakes Coast). Their average alarmed level is significantly higher than

that of the no-loss-experience group. For respondents who have had loss

experience of all three events, the average alarmed level further increases

and exceeds % in all areas. The single loss experience of a hurricane does

not significantly increase individuals’ response to climate change possibly

because the hurricane experience happened decades ago. The availability

heuristic, or availability bias,

17

theory suggests that individuals may primarily

rely on recent experience or information when evaluating a decision.

Note: The asterisk (*) denotes a statistically significant and higher percent compared to the

No-Loss-Experience group.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and

probability. Cognitive psychology, (), -.

Pacific Ocean Coast

Gulf Ocean Coast

Atlantic Ocean Coast

Great Lakes Coast

Not Coast

Pacific Ocean Coast

Gulf Ocean Coast

Atlantic Ocean Coast

Great Lakes Coast

Not Coast

Pacific Ocean Coast

Gulf Ocean Coast

Atlantic Ocean Coast

Great Lakes Coast

Not Coast

38% 55%

30% 31%

35% 38%

34% 33%

28% 37%

38% 63%

30% 48%

35% 66%

34% 29%

28% 45%

*

*

*

*

38% 72%

30% 73%

35% 80%

34% 73%

28% 72%

*

*

*

*

*

Average Percent of Alarmed Respondents by Loss Experience

No Loss Experience vs. All of Hurricane, Wildfire, & Earthquake Experience

No Loss Experience vs. Hurricane & Wildfire Experience

No Loss Experience vs. Hurricane only Experience

Naic CIPR : extreme Weather aNd property iNsuraNce

Six Americas Level by Trouble Obtaining or

Renewing Homeowners Insurance

Here, we looked at whether individuals exhibit a higher alarmed level when

they have had trouble getting or renewing homeowners insurance due to

an increase in natural disasters. We expected that individuals who had ever

been unable to obtain or renew insurance coverage would be more worried

about climate change risk because they were not financially protected

against natural disaster losses. The chart below shows a consistent result. In

all areas, the average percent of alarmed respondents is statistically higher

for respondents with trouble (Yes group) than for respondents without

trouble (No group). The difference is even larger in Not Coast and Great

Lakes Coast states: Individuals in non-coastal areas were more afraid and,

thus, more concerned about climate change when they were turned down

by insurers due to increased natural disasters.

Note: The asterisk (*) denotes a statistically significant difference comparing the Yes group to

the No group.

63%

69%

43%

64%

29%

38%

73%

34%

73%

32%

Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No

Pacific Ocean Coast Gulf Ocean Coast Atlantic Oceans Coast Great lakes Coast Not Coast

Average Percent of Alarmed Respondents by Trouble Buying Homeowners Insurance

Yes/No: Whether individual have trouble getting or renewing homeowners insurance

due to an increase in natural disasters?

Avg. Percent of the Alarmed

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0.0

**

*

*

*