REFUGEE, ASYLUM, AND INTERNATIONAL OPERATIONS DIRECTORATE (RAIO)

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO DIRECTORATE – OFFICER TRAINING

RAIO Combined Training Program

NEXUS –

PARTICULAR SOCIAL GROUP

TRAINING MODULE

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 2 of 57

This Page Left Blank Intentionally

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 3 of 57

RAIO Directorate – Officer Training / RAIO Combined Training Program

NEXUS – PARTICULAR SOCIAL GROUP

Training Module

MODULE DESCRIPTION:

This module discusses membership in a particular social group (PSG), one of the

protected grounds in the refugee definition codified in the Immigration and Nationality

Act. The discussion describes membership in a particular social group (PSG) and

examines its interpretation in administrative and judicial case law. The primary focus of

this module is the determination as to whether an applicant has established that past harm

suffered or future harm feared is on account of membership in a particular social group.

TERMINAL PERFORMANCE OBJECTIVE(S)

Given a request to adjudicate either a request for asylum or a request for refugee status,

the officer will be able to apply the law (statutes, regulations and case law) to determine

whether an applicant is eligible for the requested relief.

ENABLING PERFORMANCE OBJECTIVES

1. Explain factors to consider in determining whether persecution or feared persecution

is on account of membership in a particular social group.

•

INSTRUCTIONAL METHODS

• Interactive Presentation

• Discussion

• Practical Exercises

METHOD(S) OF EVALUATION

• Multiple-choice exam

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 4 of 57

REQUIRED READING

1. Matter of M-E-V-G-, 26 I&N Dec. 227 (BIA 2014)

2. Matter of W-G-R-, 26 I&N Dec. 208 (BIA 2014)

3. Matter of A-B-, 28 I&N Dec. 307 (A.G. 2021)

4. Matter of A-R-C-G-, 26 I&N Dec. 388 (BIA 2014)

5. Matter of L-E-A-, 27 I&N Dec. 40 (BIA 2017)

Required Reading – International and Refugee Adjudications

Required Reading – Asylum Adjudications

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

1. Matter of C-A-, 23 I&N Dec. 951 (BIA 2006)

2. Matter of Acosta, 19 I&N Dec. 211, 233-34 (BIA 1985)

3. Lynden D. Melmed, USCIS Chief Counsel. Guidance on Matter of C-A-,

Memorandum to Lori Scialabba, Associate Director, Refugee, Asylum and

International Operations (Washington, DC: January 12, 2007).

4. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Guidelines on International

Protection: “Membership of a particular social group” within the context of Article

1A(2) of the 1951 Convention and/or its 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of

Refugees. HCR/GIP/02/02, 7 May 2002, 5 pp.

5. Phyllis Coven. INS Office of International Affairs. Considerations For Asylum

Officers Adjudicating Asylum Claims From Women (Gender Guidelines),

Memorandum to all INS Asylum Officers, HQASM Coordinators (Washington, DC:

26 May 1995), 19 p. See also RAIO Training Module, Gender-Related Claims.

6. Rosemary Melville. INS Office of International Affairs. Follow Up on Gender

Guidelines Training, Memorandum to Asylum Office Directors, SAOs, AOs

(Washington, DC: 7 July 1995), 8 p.

7. Paul W. Virtue. INS Office of General Counsel. Whether Somali Clan Membership

May Meet the Definition of Membership in a Particular Social Group under the INA,

Memorandum to Kathleen Thompson, INS Office of International Affairs

(Washington, DC: 9 December 1993), 7 p.

Additional Resources – International and Refugee Adjudications

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 5 of 57

Additional Resources – Asylum Adjudications

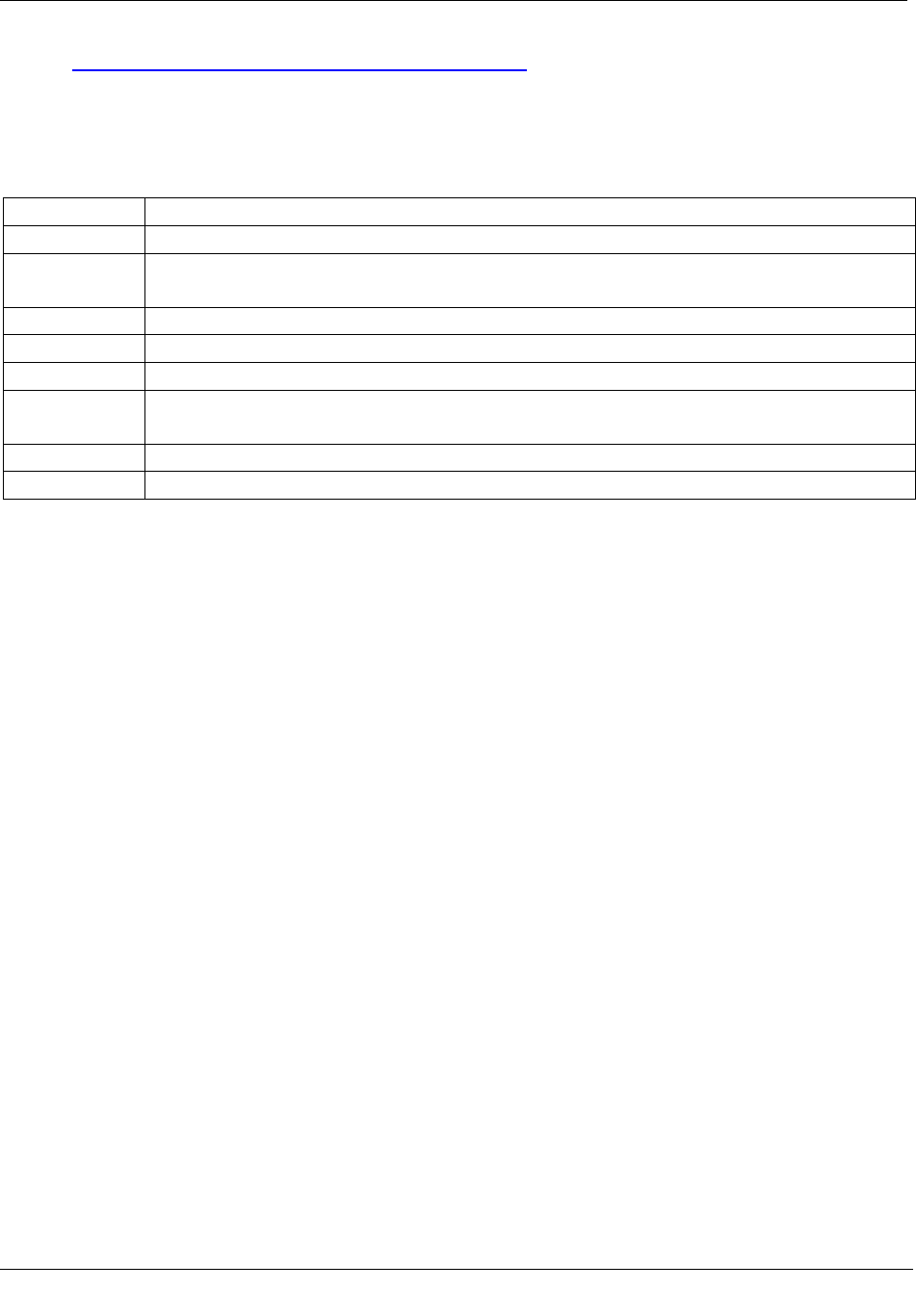

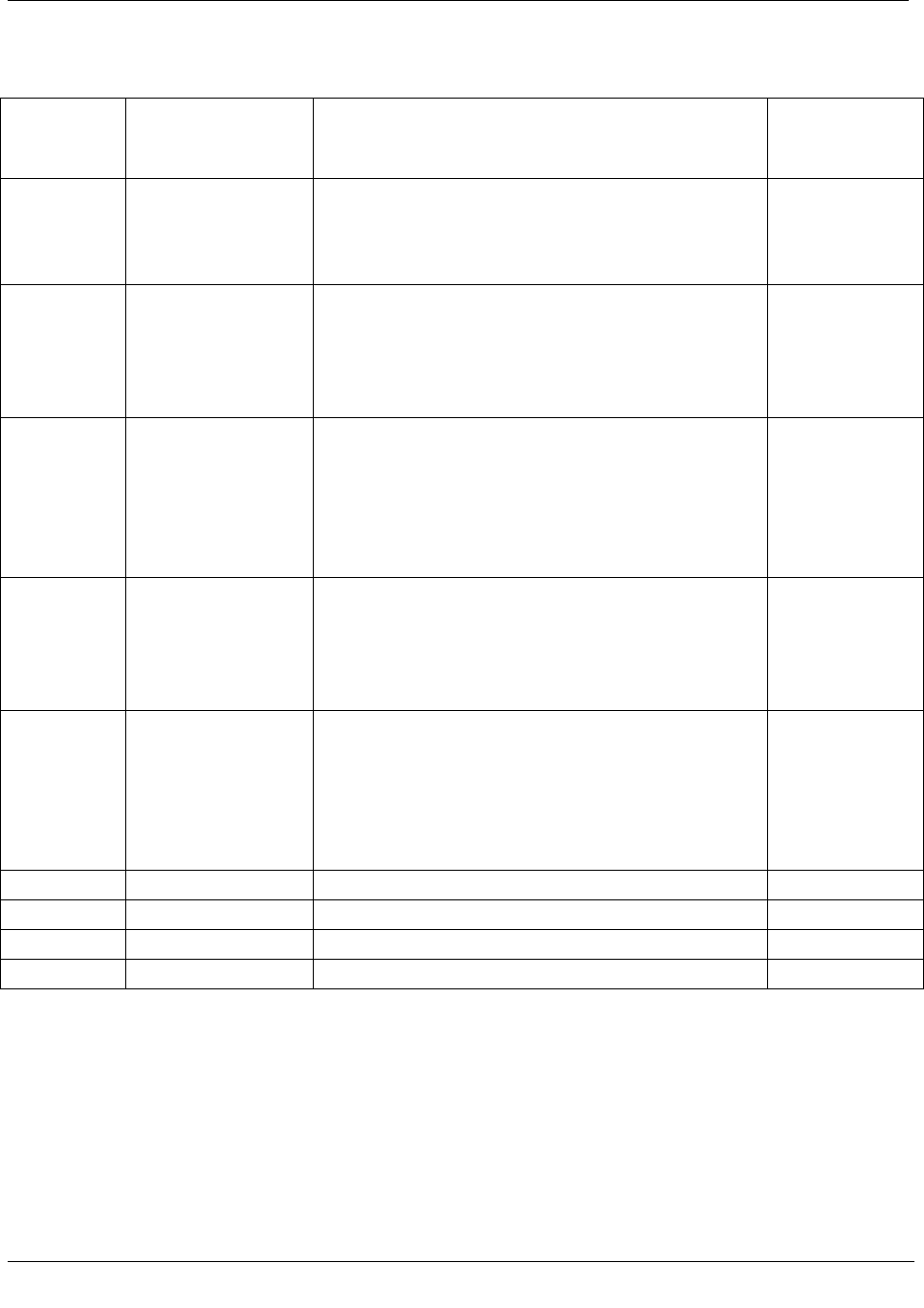

CRITICAL TASKS

Task/ Skill # Task Description

ILR6

Knowledge of U.S. case law that impacts RAIO (3)

ILR9

Knowledge of policies and procedures for processing lesbian, gay, bisexual and

transgender (LGBT) claims (3)

ILR10

Knowledge of policies and procedures for processing gender-related claims (3)

ILR14

Knowledge of nexus to a protected characteristic (4)

ILR15

Knowledge of the elements of each protected characteristic (4)

DM2

Skill in applying legal, policy and procedural guidance (e.g., statutes, precedent

decisions, case law) to information and evidence) (5)

RI1

Skill in identifying issues of claim (4)

RI2

Skill in identifying the information required to establish eligibility (4)

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 6 of 57

SCHEDULE OF REVISIONS

Date

Section

(Number and

Name)

Brief Description of Changes

Made By

11/6/2013

Summary (of

4/30/2013

edition)

Revised last sentence of paragraph 1 of

Summary and corrected corresponding

footnote # 114; added an additional sentence

as clarification.

J. Kochman

2/4/2014

Additional

Resources

Removed Dea Carpenter memo (not yet

accepted)

L. Gollub

(incorporated

by V. Conley

and J.

Stadnick)

7/27/2015

Throughout LP

Substantial revision of LP for updated case

law and new guidance:

ASM QA,

ASM

Training,

RAD TAQA,

RAIO

Training

12/20/2019

Entire Lesson

Plan; Added

Disclaimer;

Required

Readings

Minor edits to reflect changes in

organizational structure of RAIO; added

disclaimer textbox regarding updated case law

to p. 9; added required readings to p. 4; no

other substantive updates

RAIO

Training

7/20/2021

“Important Note

about Updated

Case Law”

Disclaimer;

Required

Readings

Updated to reflect vacatur of Matter of A-B-,

27 I&N Dec. 316 (A.G. 2018) (“A-B- I”),

Matter of A-B-, 28 I&N Dec. 199 (A.G. 2021)

(“A-B- II”), and Matter of L-E-A-, 27 I&N

Dec. 581 (A.G. 2019) (“L-E-A- II”); fixed

broken links

RAIO

Training,

OCC

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 7 of 57

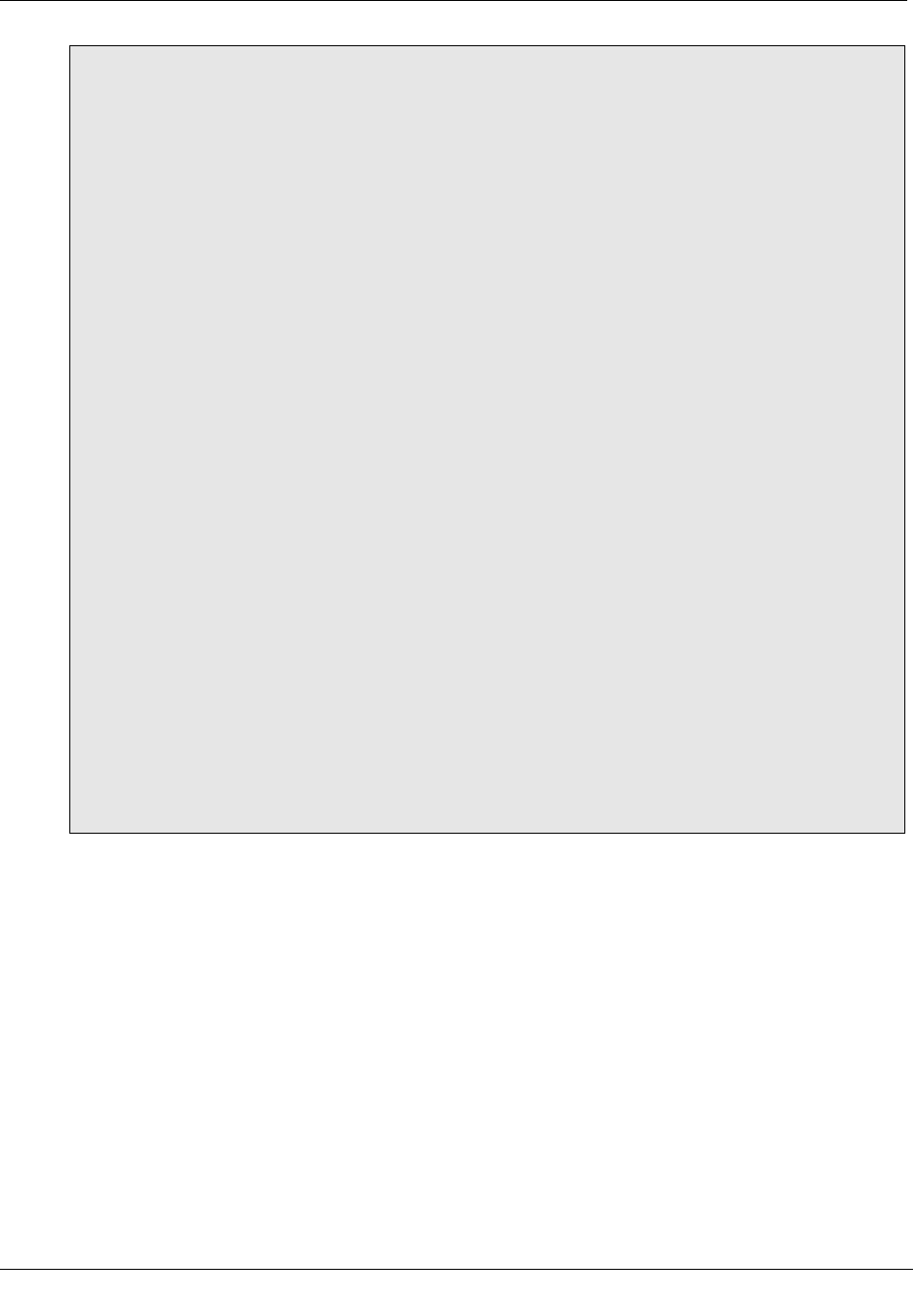

Table of Contents

1. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................10

2. DOES THE APPLICANT POSSESS A PROTECTED CHARACTERISTIC? ...................................11

2.1 Is the Applicant a Member of a Particular Social Group? ...............................................11

2.2 General Principles for Formulating Particular Social Groups ..........................................18

3. IS THE PERSECUTION OR FEARED PERSECUTION “ON ACCOUNT OF” THE APPLICANT’S

PARTICULAR SOCIAL GROUP MEMBERSHIP? ......................................................................21

4. PRECEDENT DECISIONS (SPECIFIC GROUPS) .......................................................................22

4.1 Family Membership .........................................................................................................22

4.2 Clan Membership .............................................................................................................24

4.3 Age ...................................................................................................................................25

4.4 Gender ..............................................................................................................................26

4.4.1 Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) ................................................................................26

4.4.2 Widows ..........................................................................................................................27

4.4.3 Gender-Specific Dress Codes ........................................................................................28

4.5 Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Intersex (LGBTI) ..........................................29

4.6 Domestic Violence ...........................................................................................................30

4.6.1 Women Who Are Unable to Leave a Domestic Relationship or Women Who Are

Viewed as Property by Virtue of their Position within a Domestic Relationship .........30

4.6.2 Other Types of Domestic Relationships ........................................................................31

4.6.3 Children in Domestic Relationships ..............................................................................32

4.7 Ancestry ............................................................................................................................34

4.8 Individuals with Physical or Mental Disabilities .............................................................35

4.9 Unions ..............................................................................................................................36

4.10 Students and Professionals ...............................................................................................37

4.11 Small-Business Owners Indebted to Private Creditors ....................................................37

4.12 Landowners ......................................................................................................................37

4.13 Groups Based on “Wealth” or “Affluence” .....................................................................39

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 8 of 57

4.14 Present or Former Employment in Either Law Enforcement or the Military ..................40

4.14.1 Former Military/Police Membership .............................................................................40

4.14.2 Current Military/Police Membership ............................................................................42

4.15 Drug Traffickers ...............................................................................................................43

4.16 Criminal Deportees ...........................................................................................................44

4.17 Persons Returning from the United States .......................................................................44

4.18 Tattooed Youth .................................................................................................................45

4.19 Individuals Resisting and Fearing Gang Recruitment, and Opposition to Gang Authority45

4.20 Non-Criminal Informants, Civilian Witnesses, and Assistance to Law Enforcement .....46

4.21 Gang Members .................................................................................................................50

4.22 Former Gang Members ....................................................................................................51

5. SUMMARY ..............................................................................................................................51

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 9 of 57

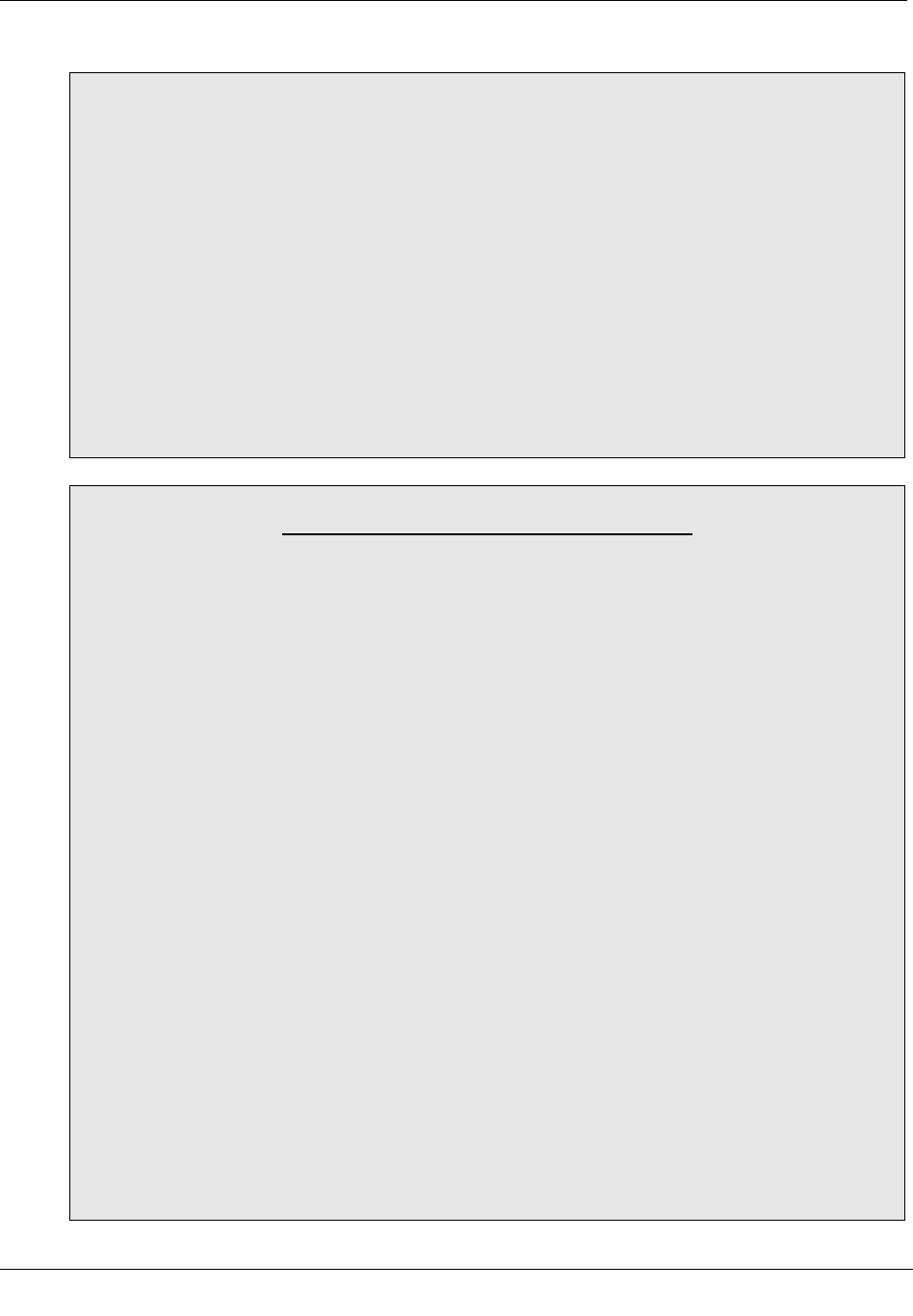

Throughout this training module, you will come across references to adjudication-

specific supplemental information located at the end of the module, as well as links

to documents that contain adjudication-specific, detailed information. You are

responsible for knowing the information in the referenced material that pertains to

the adjudications you will be performing.

For easy reference, supplements for international and refugee adjudications are in

pink and supplements for asylum adjudications are in yellow.

You may also encounter references to the legacy Refugee Affairs Division (RAD)

and the legacy International Operations Division (IO). RAD has been renamed the

International and Refugee Affairs Division (IRAD) and has assumed much of the

workload of IO, which is no longer operating as a separate RAIO division.

Important Note about Updated Case Law

On June 16, 2021, the Attorney General issued a pair of decisions vacating Matter

of A-B-, 27 I&N Dec. 316 (A.G. 2018) (“A-B- I”), Matter of A-B-, 28 I&N Dec.

199 (A.G. 2021) (“A-B- II”), and Matter of L-E-A-, 27 I&N Dec. 581 (A.G. 2019)

(“L-E-A- II”) in their entirety. See Matter of A-B-, 28 I&N Dec. 307 (A.G. 2021)

and Matter of L-E-A-, 28 I&N Dec. 304 (A.G. 2021). Accordingly, RAIO officers

should not rely upon these vacated decisions or the associated USCIS Policy

Memoranda from July 11, 2018 (Matter of A-B-) and September 30, 2019 (Matter

of L-E-A-), or any other USCIS guidance or training materials that reference these

documents, to the extent they are based on the vacated decisions.

In both decisions, the Attorney General noted the President’s executive order

directing the Attorney General and the Secretary of Homeland Security to

promulgate joint regulations addressing the circumstances in which a person

should be considered a member of a particular social group. Matter of A-B-, 28

I&N Dec. at 308; Matter of L-E-A-, 28 I&N Dec. at 304-05 (citing Exec. Order No.

14010, § 4(c)(ii), 86 Fed. Reg. 8267, 8271 (Feb. 2, 2021)). As such, the particular

social group issues addressed by these decisions will be the subject of forthcoming

rulemaking, where they can be resolved with the benefit of a full record and public

comment.

Pending rulemaking, adjudicators are directed to follow pre-A-B- I precedent,

including Matter of A-R-C-G-, 26 I&N Dec. 388 (BIA 2014), which had been

overruled by the Attorney General in A-B- I. In Matter of A-R-C-G-, the Board of

Immigration Appeals (“BIA” or “Board”) held that “married women in Guatemala

who are unable to leave their relationship” can constitute a cognizable particular

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 10 of 57

social group that forms the basis of a claim for asylum, depending on the facts and

evidence in the individual case. A-R-C-G- is discussed in more detail in Sections

2.1, Is the Applicant a Member of a Particular Social Group? and 4.6, Domestic

Violence, in this lesson plan. Adjudicators also should follow the guidance in

DHS’s brief to the Board in Matter of L-R-, which is discussed in Section 4.6,

Domestic Violence, in this lesson plan.

Similarly, adjudicators are directed to rely on pre-L-E-A- II precedent, including

Matter of L-E-A-, 27 I&N Dec. 40 (BIA 2017) (“L-E-A- I”). In that case, the BIA

held that the respondent’s father’s immediate family qualified as a particular social

group, reiterating its “long recognized” position “that family ties may meet the

requirements of a particular social group depending on the facts and circumstances

of the case.” Id. at 42. The BIA stated that not all attenuated family ties will satisfy

the particularity and social distinction criteria, and the analysis “will depend on the

nature and degree of the relationships involved and how those relationships are

regarded by the society in question.” Id. at 42-43. The BIA also upheld the

Immigration Judge’s finding that the cartel was not motivated to harm the

respondent on account of his family status. Rather, based on the specific facts in

the record, the persecutor was motivated to target the respondent because he was in

a position to provide access to his father’s store, where the cartel wanted to

increase its profits by selling contraband, and the respondent’s membership in his

family was an incidental reason for the harm. Id. at 46-47. Family-based particular

social groups are discussed in Sections 4.1, Family Membership, and 4.2, Clan

Membership, in this lesson plan.

Further guidance and substantive revisions to this lesson plan are forthcoming as of

the last revision date (see schedule of revisions). In the meantime, the “Required

Reading” list, above, has been updated to reflect the Board’s currently binding

decisions on these topics.

1. INTRODUCTION

The refugee definition at INA §101(a)(42) states that an individual is a refugee if he or

she establishes past persecution or a well-founded fear of future persecution on account

of one or more of the five protected grounds. All of the elements of the refugee definition

are reviewed in the RAIO Training Module, Refugee Definition. The requirements for an

applicant to establish eligibility based on past persecution are discussed in the module,

Persecution. The elements necessary to establish a well-founded fear of future

persecution are discussed in the module, Well-Founded Fear. The analysis of the

persecutor’s motive and the requirements needed to establish that persecution or feared

persecution is “on account of” race, religion, nationality, or political opinion are

discussed in the module, Nexus and the Protected Grounds (minus PSG).

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 11 of 57

This module provides you with an understanding of the requirements needed to establish

whether persecution or feared persecution is “on account of” membership in a particular

social group (PSG).

The nexus analysis for particular social group claims is fundamentally the same as it is

for cases involving the other protected characteristics; you must determine:

1. whether the applicant possesses or is perceived to possess a protected characteristic;

and

2. whether the persecution or feared persecution is on account of that protected

characteristic.

2. DOES THE APPLICANT POSSESS A PROTECTED CHARACTERISTIC?

The first question is the starting point for all protected grounds – whether the applicant

possesses, or is perceived to possess, a protected characteristic: membership in a

particular social group. Membership in a particular social group may overlap with other

protected grounds, such as political opinion, and you should also consider whether the

applicant can establish eligibility based on a different protected ground.

For cases based on membership in a particular social group, the analysis is expanded,

requiring you to identify the characteristics that form the particular social group and

explain why persons with those characteristics form a particular social group within the

meaning of the refugee definition.

Determining whether a specific group constitutes a particular social group can be a

complicated task. Recognizing this complexity, the Board of Immigration Appeals has set

forth a three-part test for evaluating whether a group meets the definition of a particular

social group.

1

While looking to precedential decisions from the Board and the circuit

courts of appeals may help inform your decision, you must apply the analysis discussed

below to the facts of each individual case.

2.1 Is the Applicant a Member of a Particular Social Group?

An applicant who is seeking asylum or refugee status based on membership in a

particular social group must establish that the group is (1) composed of members who

1

Matter of M-E-V-G-, 26 I&N Dec. 227 (BIA 2014); Matter of W-G-R-, 26 I&N Dec. 208 (BIA 2014).

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 12 of 57

share a common immutable characteristic, (2) socially distinct within the society in

question, and (3) defined with particularity.

2

All three elements must be established.

It is important to remember that membership in a particular social group may be imputed

to an applicant who is not, in fact, a member of a particular social group.

Step One: Common Immutable Characteristic

The group must comprise individuals who share a common, immutable characteristic,

meaning it is one that the members of the group either cannot change, or should not be

required to change because it is fundamental to each member’s identity or conscience.

3

The defining characteristic can be a shared innate characteristic, a shared past experience,

or a social or other status.

4

Unchangeable Characteristics

Unchangeable characteristics are traits that cannot be changed. Some examples of

characteristics that cannot be changed include innate ones, like gender, race, ethnicity,

skin color, and family relationships.

5

Some of these characteristics are biological traits of

a person. Others might be shared past experiences that cannot be changed because a

person is unable to change the past.

Fundamental Characteristics

Fundamental characteristics are traits, beliefs, or statuses that a person should not be

required to change because they are essential to the individual’s identity or conscience. In

analyzing this type of claim, you should consider both how the applicant experiences the

trait as part of his or her identity and whether the trait is fundamental from an objective

point of view. With regard to the latter, you may consider whether human rights norms

suggest the characteristic is fundamental. An example of a shared trait that is fundamental

to an individual’s identity or conscience is having intact genitalia in the female genital

mutilation (FGM) context. In contrast, even though an applicant may consider being a

member of a terrorist or criminal organization as being fundamental to his or her identity

or conscience, there is no basic human right to pursue such an association, and it would

not be considered fundamental from an objective point of view.

6

2

Matter of M-E-V-G-, 26 I&N Dec. at 237; Matter of W-G-R-, 26 I&N Dec. at 212-218; see also Matter of A-R-C-G-, 26 I&N

Dec. 388 (BIA 2014) (applying to a domestic violence scenario the three-part test put forth in Matter of M-E-V-G- and Matter of

W-G-R-.)

3

Matter of Acosta, 19 I&N Dec. 211, 233 (BIA 1985).

4

Id. at 233-34; Matter of W-G-R-, 26 I&N Dec. at 212-13; Matter of A-R-C-G-, 26 I&N Dec. at 392-393.

5

See Fatin v. INS, 12 F.3d 1233, 1239 (3d Cir. 1993); Matter of Kasinga, 21 I&N Dec. 357, 366 (BIA 1996).

6

See Arteaga v. Mukasey, 511 F.3d 940, 946 (9th Cir. 2007) (the court noted, “we would be hard-pressed to agree with the

suggestion that one who voluntarily associates with a vicious street gang that participates in violent criminal activity does so for

reasons so fundamental to ‘human dignity’ that he should not be forced to forsake the association”).

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 13 of 57

In Matter of Acosta, 19 I&N Dec. 211, 234 (BIA 1988), the Board explained that the

unchangeable characteristic or fundamental characteristic is part of the definition of a

particular social group because each of the other four protected grounds describe

persecution aimed at an immutable characteristic.

7

Therefore, the Board interpreted the

term “particular social group” consistently with the other grounds of persecution in the

INA, explaining that “the concept that refuge is restricted to individuals who are either

unable by their own actions, or as a matter of conscience should not be required, to avoid

persecution.”

8

Assumption of Risk Considerations

In some cases, the applicant’s voluntary assumption of an extraordinary risk of serious

harm in taking on the trait that defines the group may be evidence of fundamentality.

9

An

applicant’s decision to assume significant risks can, in some cases, provide evidence that

the belief or trait is fundamental to the applicant’s identity or conscience.

10

The relevance

of an applicant’s voluntary assumption of risk must be considered on a case-by-case

basis. Not all individuals assume the risk of a particular activity because the activity is

fundamental to their identity.

11

For example, an individual may assume the risk of a

particular activity for monetary gain, and in such a case that assumption of risk may

undercut fundamentality.

12

Step Two: Social Distinction

A group’s shared characteristic must be perceived as distinct by the relevant society.

13

This element has sometimes been referred to as “social visibility.” However, in its rulings

in Matter of M-E-V-G-, 26 I&N Dec. 227 (BIA 2014) and Matter of W-G-R-, 26 I&N

Dec. 208 (BIA 2014), the Board renamed “social visibility” as “social distinction” to

avoid confusion.

14

The Board emphasized that “social distinction” does not require the

shared characteristic to be seen by society (i.e., visible); instead the group characteristic

must be perceived as distinct by society.

15

There must be evidence indicating “that a

7

Matter of Acosta, 19 I&N Dec. at 233-34.

8

Id.

9

See Lynden D. Melmed, USCIS Chief Counsel, Guidance on Matter of C-A-, Memorandum to Lori Scialabba, Associate

Director, Refugee, Asylum and International Operations (Washington, DC: January 12, 2007).

10

Id. at 3.

11

Lynden D. Melmed, USCIS Chief Counsel, Guidance on Matter of C-A-, Memorandum to Lori Scialabba, Associate Director,

Refugee, Asylum and International Operations (Washington, DC: January 12, 2007).

12

Id.

13

Matter of W-G-R-, 26 I&N Dec. at 216.

14

Matter of M-E-V-G-, 26 I&N Dec. at 240; Matter of W-G-R-, 26 I&N Dec. at 216.

15

Matter of M-E-V-G-, 26 I&N Dec. at 240; Matter of W-G-R-, 26 I&N Dec. at 216.

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 14 of 57

society in general perceives, considers, or recognizes persons” as a group.

16

This

requirement can be met by showing that the society in question sets apart or differentiates

between people who possess the shared belief or trait and people who do not, even if

individual group members are not visibly recognized as group members. In other words,

if the common immutable characteristic were known, those with the characteristic in the

society in question would be meaningfully distinguished from those who do not have it.

17

The Board’s interpretation of “social distinction” is consistent with USCIS’s

longstanding interpretation of the term.

18

In some circumstances, members of a group may be visibly recognizable, but society may

also consider persons to be a group without being able to identify the members by sight.

Board cases have recognized groups that were not ocularly visible. For instance, in

Matter of Kasinga, 21 I&N Dec. 357, 365-66 (BIA 1996), the Board determined that

young women from a certain ethnic group in Togo who have not been previously

subjected to FGM but are opposed to it constitute a particular social group. In Matter of

Toboso-Alfonso, 20 I&N Dec. 819, 822-23 (BIA 1990) the Board held that

“homosexuals” in Cuba were a particular social group. In Matter of Fuentes, 19 I&N

Dec. 658 (BIA 1988), the Board concluded that former national police members could be

a particular social group in some circumstances. These cases illustrate the point that

ocular visibility is not required. In such cases, it may not be easy or possible to identify

who has not been subjected to or is opposed to FGM, who is gay, or who is a former

member of the national police.

19

Social distinction must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis and society-by-society

basis

As previously noted, for social distinction, there must be evidence showing that society in

general perceives or considers people who share a particular characteristic as distinct.

20

Evidence such as country conditions, witness testimony, and press accounts may

establish that a group is distinct.

21

The Board has emphasized that the social distinction

determination must be made on a case-by-case basis.

22

Laws, policies, or cultural

practices of a society, as well as governmental or non-governmental programs targeting

certain groups, may also establish social distinction. For instance, in evaluating whether

16

Matter of W-G-R-, 26 I&N Dec. at 217.

17

Matter of M-E-V-G-, 26 I&N Dec. at 238.

18

See, e.g., Lynden D. Melmed, USCIS Chief Counsel, Guidance on Matter of C-A-, Memorandum to Lori Scialabba, Associate

Director, Refugee, Asylum and International Operations (Washington, DC: January 12, 2007).

19

Matter of M-E-V-G-, 26 I&N Dec. at 240.

20

Matter of W-G-R-, 26 I&N Dec. at 217 (BIA 2014).

21

Matter of M-E-V-G-, 26 I&N Dec. at 244 (BIA 2014); see also Matter of A-R-C-G-, 26 I&N Dec. 388, 394 (BIA 2014)

(discussing the types of evidence that may show social distinction in domestic violence-related particular social groups, including

evidence that the society recognizes the need to offer protection to victims of domestic violence and other sociopolitical factors).

22

Matter of M-E-V-G-, 26 I&N Dec. at 242.

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 15 of 57

Guatemalan widows are socially distinct, you could research whether the Guatemalan

government has laws and policies addressing the needs of widows, and whether NGOs

have assistance programs helping widows. In Matter of A-R-C-G-, the Board explained

that evidence that a certain group is protected within a society could establish social

distinction.

23

The Board and the courts have not limited the types of society-specific

evidence upon which you can rely. In another context, a society might have songs or

poetry about witnesses who testify in court against members of criminal groups, and this

could serve as some evidence that such witnesses might be distinct in that society. The

individual group member’s treatment may be relevant to whether such a group is socially

distinct. The relevant society may include the entire country or a particular region or

community within the country. Accordingly, you should consider all evidence before you

to determine whether or not the proposed group is socially distinct.

Examining the Board’s holdings in M-E-V-G-and W-G-R-, the Ninth Circuit also has

emphasized that the analysis must be case-specific and society-specific.

24

The Ninth

Circuit noted that “[i]t is an error…to assume that if a social group related to the same

international gang…has been found non-cognizable in one society, it will not be

cognizable in any society. Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Panama

have used different strategies for combating gang violence…[and] these different local

responses to gangs in nations with distinct histories…may well result in a different social

recognition of social groups opposed to gang violence….” The Ninth Circuit concluded

that “the agency must make a case-by-case determination as to whether the group is

recognized by the particular society in question . . . [and] may not reject a group solely

because it had previously found a similar group in a different society to lack social

distinction.”

25

The Second Circuit also has examined the Board’s holdings in M-E-V-G-

and W-G-R- and remanded a case for the Board to conduct additional case-specific

analysis.

26

This case-specific approach is not new. In Matter of A-M-E- & J-G-U-, 24 I&N Dec. 69

(BIA 2007), the Board indicated that determining whether a group has a socially distinct

shared characteristic must be “considered in the context of the country of concern and the

persecution feared.”

27

In A-M-E- & J-G-U-, the Board reviewed country conditions to

evaluate whether, in context, the proposed particular social group members shared

socially distinct characteristics. The Board found that the applicants did not establish the

existence of a particular social group because the proposed particular social group –

“affluent Guatemalans” – did not share a common trait that was socially distinct in

23

Matter of A-R-C-G-, 26 I&N Dec. at 394.

24

Pirir-Boc v. Holder, 750 F.3d 1077 (9th Cir. 2014).

25

Id. at 1084 n.7.

26

Paloka v. Holder, 762 F.3d 191, 198 (2d Cir. 2014) (instructing the Board to determine whether the proposed groups of “young

Albanian women” or “young Albanian women between the ages of 15 and 25” qualified as cognizable social group).

27

Matter of A-M-E- & J-G-U-, 24 I&N Dec. 69, 74 (BIA 2007); cf. Tapiero de Orejuela v. Gonzales, 423 F.3d 666, 672 (7th Cir.

2005).

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 16 of 57

Guatemalan society.

28

In that case, the country of origin information before the Board

demonstrated that “affluent Guatemalans” were not at greater risk of criminality or

extortion than the general population. Instead the country of origin information

demonstrated that criminality is pervasive in all Guatemalan socio-economic groups. The

report indicated that impoverished Indians were also subjected to both crimes. For the

same reason, the Board also rejected the following possible formulations of the group:

“wealth,” “upper income level,” “socio-economic level,” “the monied class,” and “the

upper class.” The Board specifically noted, however, that wealth- or class-based social

groups must be analyzed in context, and that, under some circumstances, such groups

might qualify as particular social groups.

29

For example, should a government institute a

policy of imprisoning and mistreating persons with assets or income above a fixed level,

there could be a basis for a societal perception that the class of wealthy persons, as

defined by the government, would constitute a particular social group.

30

Because case-specific analysis is required, it is critical for you to look at all relevant

information, including the applicant’s individual circumstances, the circumstances

surrounding the events of persecution, and country of origin information, before making a

social distinction determination. Country of origin information indicating that the

immutable characteristic reflects societal distinctions is relevant when analyzing whether

a group constitutes a particular social group.

31

The group does not have to self-identify as a group and members may hide their

membership

It is not necessary for a group to identify itself explicitly as a group in order for the social

distinction requirement to be met. In addition, the fact that a member of a particular

social group may make efforts to hide his or her membership to avoid persecution does

not prevent such a group from constituting a cognizable particular social group.

32

Accordingly, a group may not appear cohesive and may not display the traditional

hallmarks of a group that shows its existence openly.

If the society in question

distinguishes people who possess the immutable trait from others because of their shared

belief or characteristic, then the group is socially distinct.

33

28

See also Donchev v. Mukasey, 553 F.3d 1206, 1218-1219 (9th Cir. 2009) (“friends of Roma individuals or of the Roma people”

not a socially distinct group, in part, because country conditions did not show that members of the group, such as the applicant’s

family members, were viewed or treated by Bulgarian society in a uniform manner).

29

Matter of A-M-E- & J-G-U-, 24 I&N Dec. at 75, n.6.

30

Id.; see also Tapiero de Orejuela, 423 F.3d at 672 (finding that a particular social group of educated, wealthy, landowning,

cattle-farming Colombians, was a cognizable group because the group was not defined merely by wealth).

31

See Castellano-Chacon v. INS, 341 F.3d 533, 548 (6th Cir. 2003) (noting that a society’s reaction to a group may provide

evidence that a particular social group exists, so long as the persecutors’ reaction to the members of the group is not the central

characteristic of the group); see also Gomez v. INS, 947 F.2d 660, 664 (2d Cir. 1991) (“A particular social group is comprised of

individuals who possess some fundamental characteristic in common which serves to distinguish them in the eyes of a persecutor

– or in the eyes of the outside world in general.”).

32

Matter of W-G-R-, 26 I&N Dec. 208, 217 (BIA 2014).

33

Id.

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 17 of 57

Step 3: Particularity

Applicants seeking to establish membership in a particular social group must also

establish that the group is defined with sufficient particularity. The particularity

requirement relates to the group’s boundaries or the need to put outer limits on the

definition of a particular social group.

34

The term “particular[ity]” is included in the plain

language of “particular” social group and is consistent with the specificity by which race,

religion, nationality, and political opinion are commonly defined.

35

The characteristics

defining the group must provide a clear benchmark for determining who falls within the

group and who does not.

36

The group must be discrete and have definable boundaries.

37

The Board has made clear that this particularity inquiry must take into account the

perspectives of the society in question.

38

Thus, the Board noted in W-G-R- that

“landowners” might be able to meet the particularity requirement in an undeveloped,

oligarchical society but would be considered too ill-defined in the United States or

Canada.

39

The Board has upheld the principle that “major segments of the population will rarely, if

ever, constitute a distinct social group.”

40

This principle, however, does not preclude the

possibility that a large segment of society could constitute a particular social group in

some situations. The “particularity” requirement means that the group must be

identifiable and have clearly defined boundaries, and major segments of a society

frequently are not sufficiently “particular.”

You should avoid an overly broad or overly narrow characterization of a group. Courts

have held that a particular social group should not be defined so broadly as to make it

difficult to distinguish group members from others in the society in which they live, or so

narrowly that what is defined does not constitute a meaningful grouping.

41

Moreover,

even when such groups are cognizable, claims based on groups that are defined too

broadly or too narrowly may fail the nexus requirement.

34

Matter of M-E-V-G-, 26 I&N Dec. 227, 238 (BIA 2014) (citing Castellano-Chacon v. INS, 341 F.3d 533, 549 (6th Cir. 2003)).

35

Id. at 239.

36

Id. (citing Matter of A-M-E- & J-G-U-, 24 I&N Dec. at 76).

37

Id. (citing Ochoa v. Gonzales, 406 F.3d 1166, 1170-71 (9th Cir. 2005)); see also Matter of A-R-C-G-, 26 I&N Dec. 388, 393

(BIA 2014) (noting that “married,” “women,” and “unable to leave the relationship” have commonly accepted definitions within

Guatemalan society, and that these terms may be combined to create a group with discrete and definable boundaries).

38

Matter of W-G-R-, 26 I&N Dec. at 214.

39

Id. at 214-15.

40

Matter of M-E-V-G-, 26 I&N Dec. at 239 (citing Ochoa v. Gonzales, 406 F.3d 1166, 1171 (9th Cir. 2005) (holding a group of

business persons were not particular)).

41

See Sanchez-Trujillo v. INS, 801 F.2d 1571, 1575-1577 (9th Cir. 1986); Gomez v. INS, 947 F.2d 660, 664 (2d

Cir. 1991);

Lukwago v. Ashcroft, 329 F.3d 157, 172 (3d Cir. 2003); Raffington v. INS, 340 F.3d 720, 723 (8th Cir. 2003).

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 18 of 57

It also is important to remember that you should not analyze each characteristic of a

group separately and reject one piece at a time. In a case involving a proposed social

group of Tanzanians who exhibit erratic behavior and suffer from bipolar disorder, the

Fourth Circuit concluded that the Board “erred because it broke down [the petitioner’s]

group into pieces and rejected each piece, rather than analyzing his group as a whole.”

42

The court noted that “erratic behavior,” by itself, might lack particularity, but when

combined with bipolar disorder, the group would satisfy the particularity requirement.

43

The Fourth Circuit cautioned not to “miss the forest for the trees.”

44

2.2 General Principles for Formulating Particular Social Groups

A social group cannot be defined by terrorist, criminal, or persecutory activity or

association, past or present

Under general principles of refugee protection, the shared characteristic of terrorist,

criminal, or persecutory activity or association, past or present, cannot form the basis of a

particular social group.

45

Three federal courts have found that groups consisting of former gang members may

constitute particular social groups in some circumstances. For asylum cases arising within

the jurisdiction of the Fourth, Sixth, and Seventh Circuits, former membership in a gang

may form a particular social group if the former membership is immutable and the group

of former gang members is socially distinct and particular.

46

It is important to note,

though, that these court decisions were issued before the BIA’s rulings in M-E-V-G- and

W-G-R- and did not analyze whether these groups met the “social distinction” and

“particularity” criteria as articulated in those cases. Asylum officers in these circuits must

analyze whether proposed groups meet these criteria on a case-by-case basis.

47

See

42

Temu v. Holder, 740 F.3d 887, 895 (4th Cir. 2014).

43

Id.

44

Id.

45

Lynden D. Melmed, USCIS Chief Counsel, Guidance on Matter of C-A-, Memorandum to Lori Scialabba, Associate Director,

Refugee, Asylum and International Operations (Washington, DC: January 12, 2007). See, e.g., Bastanipour v. INS, 980 F.2d

1129, 1132 (7th Cir. 1992) ("Whatever its precise scope, the term ‘particular social groups’ surely was not intended for the

protection of members of the criminal class in this country….”); Arteaga v. Mukasey, 511 F.3d 940 (9th Cir. 2007) (holding that

current or former gang membership does not give rise to a particular social group due to gang members’ criminal activities);

Cantarero v. Holder, 734 F.3d 82, 85-88 (upholding the BIA’s conclusion that recognizing former members of a gang as

members of a particular social group would undermine the legislative purpose of the INA).

46

Urbina-Mejia v. Holder, 597 F.3d 360, 365–67 (6th Cir.2010) (holding that former gang members of the 18th Street gang have

an immutable characteristic and are members of a “particular social group” based on their inability to change their past and the

ability of their persecutors to recognize them as former gang members); Benitez Ramos v. Holder, 589 F.3d 426, 431 (7th Cir.

2009); Martinez v. Holder, 740 F.3d 902, 911-13 (4th Cir. 2014) (holding that the petitioner’s membership in a group of former

MS-13 members was immutable, and remanding the case to the Board to analyze the other particular social group criteria); see

also USCIS Asylum Division Memorandum, Notification of Ramos v. Holder: Former Gang Membership as a Potential

Particular Social Group in the Seventh Circuit (Mar. 2, 2010).

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 19 of 57

Asylum Adjudications Supplement – Former Gang Membership as a Particular Social

Group.

Current gang membership, however, may not be the basis for a particular social group

even in these circuits. For example, the Fourth Circuit noted:

We agree that current gang membership does not qualify as an immutable

characteristic of a particular social group….It is not the case that current gang

members “cannot change” their status as gang members, as they can leave the

gang. Nor do we think that they “should not be required to change because [gang

membership] is fundamental to their individual identities or consciences.” To so

hold would “pervert the manifest humanitarian purpose of the statute.”

48

The Fourth Circuit’s position on gang membership not being a fundamental trait is

consistent with USCIS’s position that a particular social group may not be based on

present criminal activity.

49

Avoid Circular Reasoning

A group cannot be defined solely by the fact that its members are subject to the harm that

the applicant claims to have suffered or to fear as persecution. The shared characteristic

of persecution by itself, however, does not disqualify an otherwise valid social group.

50

An otherwise valid group may be defined in part by the fact that its members are subject

to persecution if the group is defined by other viable immutable characteristics separate

from the feared persecution, or the fact of past persecution itself a basis for additional

persecution.

51

In some cases, the fact that an individual has been harmed in the past can create an

independent reason why that individual would be targeted for additional harm in the

future. In some societies, a shared past experience of having been harmed in the past may

give rise to a socially distinct, particularly defined group. For example, in some

circumstances, survivors of rape, if the rape is or were known to others, may be treated

differently from other individuals by the surrounding society and/or may face social

ostracism, or be more vulnerable to further harm as a result of their past harm. In such a

47

See also Matter of W-G-R-, 26 I&N Dec. 208, 220-222 (BIA 2014) (holding that an applicant’s proposed social group of

“former members of the Mara 18 gang in El Salvador who have renounced their gang membership” was not sufficiently

particular, because it could include people of any age, sex, and background and their participation in the gang could vary widely

in terms of strength and duration, or socially distinct, because there was not enough evidence in the record about the treatment or

status of former Mara 18 members in Salvadoran society).

48

Martinez, 740 F.3d at 912 (citations omitted).

49

See also Matter of W-G-R-, 26 I.&N. Dec. at 215 n. 5.

50

Matter of M-E-V-G-, 26 I&N Dec. 227, 243 (BIA 2014) (citing Cece v. Holder, 733 F.3d 662, 671 (7th Cir. 2013)); see also

Matter of A-M-E- & J-G-U-, 24 I&N Dec. 69, 74 (BIA 2007) (noting that the fact that members of a group have been harmed

may be a relevant factor in considering the group’s social distinction within society).

51

Cece, 733 F.3d at 671-72.

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 20 of 57

case, the fact that the initial rape was not on account of a protected trait does not preclude

a finding that subsequent harm, whether it is in the form of repeated rape or of some other

kind of harm, may be on account of a shared characteristic that the applicant obtained by

virtue of the initial rape.

52

In such scenarios, the inclusion of the initial incident of past

harm as part of the particular social group definition does not violate the rule against

circularity. Such a group formulation, however, could not provide the required nexus for

the initial incident of mistreatment for purposes of any past persecution analysis.

Another example of past harm forming the basis of a valid particular social group is the

Lukwago v. Ashcroft case, involving a Ugandan man who was forcibly recruited by the

Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) as a child.

53

He claimed past persecution based on his

membership in the particular social group of “children from Northern Uganda who are

abducted and enslaved by the LRA.”

54

The Third Circuit rejected the past persecution

claim, holding that the LRA was motivated to recruit the applicant by a desire to grow its

ranks, and not by his membership in the proposed particular social group.

55

The applicant

was not a member of the group at the time he was recruited. However, the court held that

the applicant might be able to present a claim based on his well-founded fear of future

persecution on account of a similar particular social group.

56

There may be a valid

particular social group since the experience of having been a child soldier for the LRA is

immutable, and assuming former child soldiers are socially distinct and well-defined in

Ugandan society, it could form a valid particular social group with regard to well-

founded fear.

While evidence that members of a group are harmed by either the government or private

actors can be evidence that they share a distinct trait, you should be careful to avoid

defining a particular social group solely or primarily by the harm the applicants suffer.

No size limitation

There are no maximum or minimum limits to the size of a particular social group. While

the Board has cautioned that major segments of the population will rarely constitute

distinct social groups, particular social groups may contain only a few individuals or a

large number of people.

57

52

Cf. Gomez v. INS, 947 F.2d 660, 663-4 (2d Cir. 1991) (rejecting an applicant’s claim that she would be harmed in the future as

a member of a particular social group “women previously battered and raped by Salvadoran guerrillas” because there was no

evidence that the applicant would be targeted for future harm on that basis).

53

Lukwago v. Ashcroft, 329 F.3d 157 (3d Cir. 2003) (remanding to the BIA to consider an applicant’s claim of well-founded fear

on account of being a former child soldier).

54

Id. at 167.

55

Id. at 170.

56

Id. at 178-79.

57

Matter of M-E-V-G-, 26 I&N Dec. 227, 239 (BIA 2014); Perdomo v. Holder, 611 F.3d 662, 669 (9th Cir. 2010) (reasoning

“that the size and breadth of a group alone does not preclude a group from qualifying as such a social group”).

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 21 of 57

The perception of the society in question, rather than the perception of the

persecutor, is most relevant to social distinction.

The Board has held that defining a particular social group from the perspective of the

persecutor is inconsistent with prior holdings that a social group cannot be defined

“exclusively” by the fact that a member has been subjected to harm.

58

The perception of

the applicant’s persecutors may be relevant, as it can be indicative of whether society

views the group as distinct.

59

The persecutors’ perception by itself, however, is

insufficient to make a group socially distinct.

60

No voluntary associational relationship needed

A voluntary association is not a required component of a particular social group, but can

be a shared trait that defines a particular social group.

61

Thus, a voluntary association

should be analyzed as any other trait asserted to define a particular social group.

Cohesiveness or homogeneity not required

Cohesiveness or homogeneity of group members is not a required component of a

particular social group.

62

It is not necessary that group members be similar in all or many

aspects and it is not required that the group members know each other or associate with

each other. The relevant inquiry is whether there is a shared characteristic or belief that

members share.

3. IS THE PERSECUTION OR FEARED PERSECUTION “ON ACCOUNT OF” THE

APPLICANT’S PARTICULAR SOCIAL GROUP MEMBERSHIP?

Even if an applicant establishes that he or she is a member of a particular social group,

the applicant must still establish that he or she was persecuted, or has a well-founded fear

of persecution, on account of his or her membership in the group. To determine whether

an applicant has established a nexus, you must elicit and consider all evidence, direct and

circumstantial, relevant to the motive of the persecutor.

58

Matter of M-E-V-G-, 26 I&N Dec. at 242 (disagreeing with the Ninth Circuit’s suggestion, in Henriquez-Rivas v. Holder, 707

F.3d 1081,1089 (9th Cir. 2013), that the perception of the persecutor may matter the most).

59

Id.

60

Id.

61

Matter of C-A-, 23 I&N Dec. 951,956 (BIA 2006); see Henriquez-Rivas v. Holder, 707 F.3d 1081, 1097 (9th Cir. 2013)

(acknowledging that the Board does not require members of a particular social group to share a voluntary associational

relationship); Hernandez-Montiel v. INS, 225 F.3d 1084, 1092-93 (9th Cir. 2000) (holding that a particular social group “is one

united by a voluntary association, including a former association, or by an innate characteristic that is so fundamental to the

identities or consciences of its members).

62

Matter of C-A-, 23 I&N Dec. at 957. See also Henriquez-Rivas v. Holder, 707 F.3d 1081, 1097 (9th Cir. 2013); UNHCR

Guidelines On International Protection: “Membership of a Particular Social Group", para. 15.

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 22 of 57

You must keep this step in the analysis distinct from your determinations of 1) whether a

particular social group exists, and 2) whether the applicant is a member of the group. This

step in the process is the same analysis that you must conduct with any of the four other

protected grounds.

4. PRECEDENT DECISIONS (SPECIFIC GROUPS)

Below are summaries of precedent decisions that have identified certain groups that are

particular social groups and other groups that were found not to be particular social

groups based on the specific facts of the case. These examples are not an exhaustive list.

Since this area of law is evolving rapidly, it is important to be informed about current

cases and regulatory changes. It also is important to emphasize that these decisions were

limited to the records before the Board and courts. Unlike the appellate context where the

record is already developed, you have a duty to develop the record, eliciting testimony

and researching country conditions, news reports, laws, policies, and other evidence, to

determine whether a group is cognizable in the relevant society.

63

4.1 Family Membership

When analyzed on a case-by-case basis under the framework set out in this lesson plan, in

many cases a family may constitute a particular social group. This approach is consistent

with existing case law recognizing family as a “particular social group.” For instance, the

First Circuit has held that a family constitutes the “prototypical example” of a particular

social group. The court found a link between the harm the applicant experienced and his

family membership, and concluded that the harm experienced was persecution on account

of the applicant’s membership in a particular social group (his nuclear family).

64

The

Seventh Circuit has found that parents of Burmese student dissidents share a common,

immutable characteristic sufficient to constitute a particular social group.

65

The Fourth

Circuit has found that “family members of those who actively oppose gangs in El

Salvador by agreeing to be prosecutorial witnesses” is a viable particular social group

where evidence showed that street gang members often intimidate their enemies by

attacking those enemies’ families. The court found that “[t]he family unit – centered

63

See Pirir-Boc v. Holder, 750 F.3d 1077 (9th Cir. 2014) (reiterating that “[i]t is an error . . . to assume that if a social group . . .

has been found non-cognizable in one society, it will not be cognizable in any society”); Matter of S-M-J-, 21 I&N Dec. 722, 729

(BIA 1997) (noting that the adjudicator has the duty to develop the record). As officers have limited ability to research country

conditions when interviewing refugee applicants abroad, IRAD generally provides guidance at pre-departure briefings regarding

particular social groups that have been recognized in certain regions. See International and Refugee Adjudications Supplement.

In addition, refugee adjudications take place abroad and outside of the jurisdiction of any federal circuit court of appeals.

Consequently, while case law on particular social groups may be informative in the refugee context, officers must ensure that

they have elicited sufficient testimony consistent with specific, relevant country conditions to support a social group-based claim

regardless of whether or not the particular social group has been recognized in circuit court case law.

64

Gebremichael v. INS, 10 F.3d 28, 36 (1st Cir. 1993).

65

See Lwin v. INS, 144 F.3d 505, 512 (7th Cir. 1998); see also Iliev v. INS, 127 F.3d 638, 642 (7th Cir. 1997) (recognizing that

family could constitute a particular social group).

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 23 of 57

around the relationship between an uncle and his nephew – possesses boundaries that are

at least as ‘particular and well-defined’ as other groups whose members have qualified

for asylum,” thus meeting the particularity requirement.

66

In analyzing whether a specific family group qualifies as a particular social group, the

shared familial relationship should be analyzed as the common trait that defines the

group. The immutability criterion can easily be satisfied. The right to have a relationship

with one’s family is fundamental, as it is protected by international human rights norms.

Also, familial relationships for the most part cannot be changed. Often, the determinative

question is whether the familial relationship also reflects social distinctions. That would

depend on the circumstances, including the degree and nature of the relationship asserted

to define the group and the cultural context that would inform how that type of

relationship is viewed by the society in question. The question here is not generally

whether a specific family is well-known in the society. Rather, the question is whether

the society perceives the degree of relationship shared by group members as so

significant that the society distinguishes groups of people based on that type of

relationship.

In most societies, for example, the nuclear family would qualify as a particular social

group, while those in more distant relationships, such as second or third cousins, may not.

In other societies, however, extended family groupings may have greater social

significance, such that they could meet the “social distinction” element.

67

You should

carefully analyze this issue in light of the nature and degree of relationship within the

family group and pay close attention to country of origin information about social

attitudes toward family relationships.

It is important to keep in mind that it is the family membership itself that forms the basis

for the particular social group. A case that at first glance may appear to be a personal

dispute may satisfy the nexus requirement with regard to family members; it is not

necessary that the persecutor have initially targeted the family on account of a different

protected characteristic. For example, the persecutor may target the applicant to seek

revenge on a family member with whom the persecutor has a personal dispute. Where the

persecutor is motivated to harm the victim because of the victim’s family membership,

the targeting is not in fact because of a personal dispute with the applicant or for revenge

against the applicant.

68

66

Crespin-Valladares v. Holder, 632 F.3d 117, 125-26 (4th Cir. 2011) (reversing BIA’s rejection of particular social group

comprised of family members of those who actively oppose gangs in El Salvador by agreeing to be prosecutorial witnesses).

67

Matter of H-, 21 I&N Dec. 337, 342-43 (BIA 1996) (indicating that a Somali clan or subclan represents a familial-type

relationship that is socially distinct).

68

See, e.g., Hernandez-Avalos v. Lynch, 784 F.3d 944, 950 (4th Cir. 2015) (“Hernandez’s relationship to her son is why she, and

not another person, was threatened with death if she did not allow him to join Mara 18, and the gang members’ demands

leveraged her maternal authority to control her son’s activities. The BIA’s conclusion that these threats were directed at her not

because she is his mother but because she exercises control over her son’s activities draws a meaningless distinction under these

facts. It is therefore unreasonable to assert that the fact that Hernandez is her son’s mother is not at least one central reason for

her persecution.”); Cordova v. Holder, 759 F.3d 332, 339 (4th Cir. 2014) (“The BIA certainly did not err in holding that Aquino

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 24 of 57

In many cases, multiple members of a family may have been threatened or targeted by the

same persecutor, and there may be evidence that the persecutor may have been motivated

both by the applicant’s family membership and by other factors. You must determine

whether the applicant’s family membership was a sufficient part of the persecutor’s

motive to meet the nexus standard.

In Aldana-Ramos v. Holder, for example, the First Circuit considered a case in which two

brothers applied for asylum after their father, a successful business owner, was kidnapped

for ransom by members of a criminal gang in Guatemala. Although the brothers paid the

ransom, their father was killed, and they continued to receive threats from the gang. The

First Circuit reversed the Board’s conclusion that the brothers had been threatened solely

on the basis of wealth and held that the Board had erred by failing to consider the

applicants’ contention that they had been targeted on account of their membership in their

immediate family.

69

It remanded the case to the Board for further consideration of

whether the applicants’ family membership was “one central reason” they had been

targeted as required for them to be eligible for asylum.

70

In Perlera-Sola v. Holder, by

contrast, the First Circuit upheld the Board’s determination that a Guatemalan applicant

had not met his burden to show that his family membership was a central reason for the

harm he suffered where the applicant had, along with several members of his family,

been attacked and threatened by unknown criminals because of their perceived wealth.

71

4.2 Clan Membership

A clan is an extended family group that has been found to be a particular social group.

The BIA has held that membership in a Somali sub-clan may form the basis of a

particular social group.

72

In 1993, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS)

Office of the General Counsel issued a legal opinion that a Somali clan may constitute a

particular social group.

73

Although extended family groups may not always be recognized

as particular social groups, in the Somali context, a clan is a discrete group, whose

members are linked by custom and culture.

74

Clan members also are usually identifiable

within their countries of origin as members of their clan.

[Cordova]’s cousin and uncle were targeted because of their membership in a rival gang and not because of their kinship ties. But

that holding does not provide a basis for concluding that MS–13 did not target Aquino on account of his kinship ties to his cousin

and uncle.”).

69

Aldana-Ramos v. Holder, 757 F.3d 9, 18-19 (1st Cir. 2014).

70

Id. at 19.

71

Perlera-Sola v. Holder, 699 F.3d 572, 576-577 (1st Cir. 2012).

72

Matter of H-, 21 I&N Dec. at 338 (BIA 1996).

73

Paul W. Virtue, INS Office of General Counsel, Whether Somali Clan Membership May Meet the Definition of Membership in

a Particular Social Group under the INA, Memorandum to Kathleen Thompson, Director, Refugee Branch, OIA (Washington,

DC: 9 December 1993).

74

Matter of H-, 21 I&N Dec. 337, 342-43 (BIA 1996); Malonga v. Mukasey, 546 F.3d 546 (8th Cir. 2008) (concluding that Lari

ethnic group of the Kongo tribe is a particular social group for purposes of withholding of removal; members of the tribe share a

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 25 of 57

4.3 Age

The Board noted in Matter of S-E-G- that a particular social group may be valid where

the age of the members is one of the shared characteristics. The Board stated that

although age is not strictly immutable, it may give rise to a particular social group since

“the mutability of age is not within one’s control and … if an individual has been

persecuted in the past on account of an age-described particular social group, or faces

such persecution at a time when that individual’s age places him within the group, a

claim for asylum may still be cognizable.”

75

In other words, in the context of age-based

particular social groups, you should consider the immutability of age at the time of the

events of past persecution or at the time the applicant expresses a fear of future

persecution.

Several Board and circuit court cases have addressed the validity of using age, in

conjunction with other characteristics, as the basis for a particular social group. The

Board and some courts have rejected social groups composed of young, urban males who

feared either conscription by the military or forcible recruitment by guerrillas.

76

In those

cases, the persecutors targeted the young men because they were desirable combatants. It

appears that the courts rejected the claims because of the applicants’ failure to establish

the requisite motive (“on account of”), and not because of their failure to establish

membership in a valid particular social group.

The Third Circuit, in Lukwago v. Ashcroft, noted that age changes over time, “possibly

lessening its role in personal identity.” The court further noted that children as a class

represent a large and diverse group, suggesting that the class is not particular enough.

Nevertheless, age did make up an important component in the particular social group

based on the applicant’s shared past experience in Lukwago. The court held that “former

child soldiers who escaped [Lord’s Resistance Army] enslavement” were a particular

social group at risk of persecution by the LRA and the Ugandan government because they

could not undo the shared past experience of being child soldiers.

77

The immutability of age was also taken into account by the Seventh Circuit in

considering a case involving an Albanian woman who feared being trafficked in the

future due to her youth, gender, and living alone. The court stated, “the Petitioner is part

of a group of young Albanian women who live alone. Neither their age, gender,

nationality, or living situation are alterable.”

78

Without considering the Board’s

common dialect and accent, which is recognizable to others in Congo, and members are identifiable by their surnames and by

their concentration in southern Congo's Pool region).

75

Matter of S-E-G-, 24 I&N Dec. 579, 583-84 (BIA 2008).

76

Matter of Vigil, 19 I&N Dec. 572 (BIA 1988); Sanchez-Trujillo v. INS, 801 F.2d 1571 (9th Cir. 1986); Matter of Sanchez and

Escobar, 19 I&N Dec. 276 (BIA 1985); see also Civil v. INS, 140 F.3d 52 (1st Cir. 1998); Matter of S-E-G-, 24 I&N Dec. 579

(BIA 2008); Matter of E-A-G-, 24 I&N Dec. 591 (BIA 2008).

77

Lukwago v. Ashcroft, 329 F.3d 157, 178 (3d Cir. 2003).

78

Cece v. Holder, 733 F.3d 662, 673 (7th Cir. 2013) (en banc).

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 26 of 57

requirements of social distinction and particularity, the Seventh Circuit held, “These

characteristics qualify Cece’s proposed group as a protectable social group under asylum

law.”

79

4.4 Gender

Gender is an immutable trait and has been recognized as such by the BIA and some

federal courts.

80

Courts have not yet addressed whether broad social groups based solely

on an applicant’s gender may meet the “particularity” and “social distinction”

requirements as outlined in M-E-V-G- and W-G-R-,

81

but some earlier circuit court

decisions have indicated that gender may form the basis of a particular social group in

combination with the applicant’s nationality or ethnicity and that there may be a nexus

between an applicant’s membership in that group and the harm he or she fears.

82

In most cases, though, an applicant’s status as a man or woman is not, by itself, a central

reason motivating the persecutor to harm him or her. Rather, the persecutor is motivated

to harm him or her based on membership in a group defined by gender in combination

with some other characteristic he or she possesses, such as a person’s social status in a

domestic relationship.

83

In general, you will formulate gender-related particular social

groups based on gender, nationality and/or ethnicity, and at least one other relevant trait

or characteristic. The following sections discuss some of the common gender-related

particular social groups.

4.4.1 Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)

84

FGM cases also raise gender-related issues. In Matter of Kasinga, the BIA held that

gender, in conjunction with other characteristics, formed the basis of a particular social

group. The BIA granted asylum to the applicant, who feared persecution on account of

her membership in the particular social group defined as “young women of the Tchamba-

79

Id.

80

See, e.g., Matter of Acosta, 19 I&N Dec. 211, 233 (BIA 1985) (listing “sex” as a paradigmatic example of an immutable

characteristic); Fatin v. INS, 12 F.3d 1233, 1240 (3d Cir. 1993); Matter of Kasinga, 21 I&N Dec. 357, 365-66 (BIA 1996).

81

See Paloka v. Holder, 762 F.3d 191 (2d Cir. 2014) (remanding to the BIA for consideration of whether the proposed social

groups of “young Albanian women” or “young Albanian women between 15 and 25” are proposed social groups under the M-E-

V-G- framework).

82

See Niang v. Gonzales, 422 F.3d 1187, 1199 (10th Cir. 2005) (finding that “gender plus tribal membership” may identify a

social group); Mohammed v. Gonzales, 400 F.3d 785, 797 (“the recognition that girls or women of a particular clan or nationality

(or even in some circumstances females in general) may constitute a social group is simply a logical application of our law”);

Hassan v. Gonzales, 484 F.3d 513, 518 (8th Cir. 2007). See also Fatin v. INS, 12 F.3d 1233, 1240 (3d Cir. 1993); Bah v.

Mukasey, 528 F.3d 99, 112 (2d Cir. 2008); Perdomo v. Holder, 611 F.3d 662, 668 (9th Cir. 2010).

83

See, e.g., Cece v. Holder, 733 F.3d 662, 676 (7th Cir. 2013) (en banc) (finding that the petitioner had a well-founded fear of

persecution on account of her membership in a particular social group of “young Albanian women living alone” and noting that

“the social group is defined by gender plus one or more narrowing characteristics.”).

84

Sometimes referred to as female genital cutting.

Nexus – Particular Social Group

USCIS: RAIO Directorate – Officer Training

DATE (see schedule of revisions): 7/20/2021

RAIO Combined Training Program

Page 27 of 57

Kunsuntu Tribe who have not had female genital mutilation, as practiced by that tribe,

and who oppose the practice.”

85

Case law has taken a variety of approaches to defining a particular social group in cases

involving FGM. As stated in the Attorney General’s decision on certification in Matter of

A-T-, the framework for analyzing such cases depends in critical ways on how the group

is formulated.

86

In FGM cases, you should consider whether the relevant social group should be defined

as females of a certain nationality or ethnicity who are subject to gender-related cultural

traditions. For additional guidance on FGM cases in the asylum context, see RAIO

Training Module, Well-Founded Fear.

Eligibility Based on Feared FGM of Applicant’s Children

In Matter of A-K-, the BIA made clear that an applicant cannot establish eligibility for

asylum based solely on a fear that his or her child would be subject to FGM if returned to

the country of nationality. The persecution an applicant fears must be on account of the

applicant’s protected characteristic (or protected characteristic imputed to the applicant).

When a child is subjected to FGM, it is generally not because of a parent’s protected

characteristic. Rather, the FGM is generally imposed on the child because of the child’s

characteristic of being a female who has not yet undergone FGM as practiced by her

culture.

87

If the child of an applicant were specifically targeted for FGM in order to harm the parent

because of the parent’s opposition to FGM, it might be possible to establish a nexus to

the parent’s membership in a particular social group defined as parents who oppose